A map of the ecosystems historically shaped by fire on Long Island

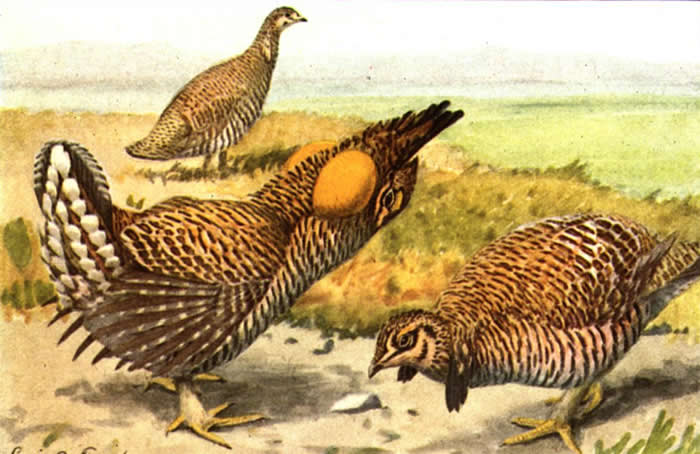

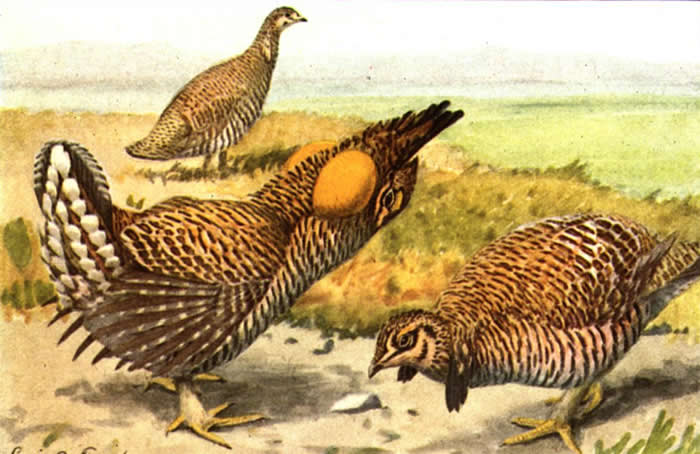

In addition to the Atlantic Coastal Pine Barrens which have been shaped by fire ecology, there is another, lesser known climax ecosystem that still exists in small remnants in the Eastern U.S. It is known at the Atlantic Coastal Prairie, Sand Plains, Dry Tall Grass Prairie, etc. These semi-arid habitats are characterized by their poor sandy soils and their need for fire regimes (and now mowing). They are home to threatened and endangered species, including Agalinus acuta (sandplain gerardia), and were once home to a now extinct species of grouse known as the Heath Hen (Tympanuchus cupido var. cupido) (Palkovacs et al., 2004), .

The extinct Heath Hen (Tympanuchus cupido var. cupido)

The endangered Sand Plain Gerardia (Agalinus acuta). The Hempstead Plains has at least 2 of the only 11 populations worldwide.

These unique eastern dry prairies still exist in isolated patches in New England and Long Island. The one I am most familiar with is the Hempstead Plains, the only naturally occurring prairie east of the Appalachian Mountains (Neidich and Kennelly, 2014). There is only around 100 acres left of the 60,000- 40,000 acres that existed prior to colonization. Since colonization, the plains have been used for farming and urban development. This has disturbed fragile topsoil crust and allowed woody and invasive plants to encroach on the grasslands. Once an important flyway for birds, the plains still serve as a home and migration stop for: wild pheasant, fox, orchard orioles, monarch butterflies, fritillaries, meadowlark, and others.

These Plains were once a vast expanse.

The Hempstead Plains exist in a highly populated county directly adjacent to the burrow of Queens in New York City. Due to their close proximity to this metropolitan area, the flat land was prime for early urban sprawl developments. However, this also made them a good place for New York City botanists to study the unique flora assemblages, and there are botanical records going back over 100 years.They all noted the rapid disappearance of the ecosystem (Harper, 1911).

A Satellite image of Garden City, NY. The red pin is the site of the managed remnant of the Hempstead Plains. The green area just south of the pins is a larger, unmanaged portion. The green area to the east are golf courses that also contain grassland remnants.

The history of the development of these plains is an interesting one. They were once a commons grazing area for sheep. Years later, they were bought by a wealthy department store owner who opened golf courses, polo fields, and race tracks to entice other wealthy people to move to the area. Then, during the early 20th century they served as a major airfield where Charles Lindberg began the first Trans-Atlantic flight.

The Plains have been subject to unrelenting development up unto the 1970’s when a large stadium was built, and the community college was expanded. In 1991, 16.3 continuous acres were put under the management of a non-profit, Friends of the Hempstead Plains, for the purpose of education and preservation. Since the founding of the organization, both students and experienced botanists have conducted experiments regarding the specific plants that grow in these particularly dry soils. The unique soils are characterized by their upper lichen-moss covered crust, and well-drained, dark horizons above glacial out-wash. The Nature Conservancy carried out multiple controlled burns in the 1990’s in order to restore balance to the scarred and trampled remnant.

Black and white film prints of the Nature Conservancy controlled burns in the 1990s

Other, largely unmanaged portions are present on a nearby golf course, and across a highway from the managed parcel. It was on this county owned unmanaged preserve where a recent 5 acre wild fire occurred in 2016, causing a more blue curls and toad flax to bloom in 2017. This was where I found two species I was searching for to collect for a restoration project, Andropogon virginicus and Schizachryum scoparium. Although these species are extremely common, I needed to find them in this specific eco-region. As I mentioned before, this county is adjacent to New York City, highly developed and populated, so finding a wild population was not a walk in the park.

Prairie Three-awn (Aristida oligantha) growing through the cracks of an old airstrip.

I also collected an annual grass, Oligantha aristida (Prairie Three-awn). This grass was growing between old slabs of asphalt and little blue stem. Talk about a tough little grass!

One of the many massive dumping sites within the unmanaged preserve.

As I walked through this rare piece of green space, in the center of a bustling city, I was disturbed by the utter neglect of management by the county. There are obviously ongoing problems of homelessness, off-roading, and dumping. I couldn’t help but notice the irony that in the shadow of a huge hotel, there are people living in tents.

Friends of the Hempstead Plains at Nassau Community College Manages 19 acres of this rare Habitat

Compared to the tall grass prairie preserves out west this is a tiny swath of land. Some might question what the point of conserving such a small amount of land really is. In the middle of a metropolitan area, this natural landscape can teach so many people about the native flora and the history of the area. I for one got my start within the botanical field volunteering on this preserve. Now after seeing dozens of different habitats throughout the Mid-Atlantic and mainland U.S., I can tell how unique a place the Hempstead Plains really is.

To learn more about this grassland, go to Friendsofhp.org

When people ask me how my internship has been, there is always a moment of fraught silence as I wrestle for a place to even begin. How can you give a glib watercooler answer about an eternity of grass, silence so deep that only the gulls and ospreys dare break it? To hours and hours pouring over hundreds of species of plants, becoming intimately aware of their endless variations? The carefully nurtured, by now almost instinctive reflex to look for diagnostic characteristics in grasses and sedges that had you in tears six months ago?

When people ask me how my internship has been, there is always a moment of fraught silence as I wrestle for a place to even begin. How can you give a glib watercooler answer about an eternity of grass, silence so deep that only the gulls and ospreys dare break it? To hours and hours pouring over hundreds of species of plants, becoming intimately aware of their endless variations? The carefully nurtured, by now almost instinctive reflex to look for diagnostic characteristics in grasses and sedges that had you in tears six months ago?