It’s no surprise that wildfires can have devastating impacts on people, wildlife, and the ecosystem. In high-severity wildfires, habitats are destroyed causing susceptible populations to decline. Such is the case for a rare species of wild onion, Allium gooddingii, better known as Gooding’s onion.

Allium gooddingii is an endemic plant to New Mexico and Arizona where it generally grows under the canopy of high-elevation mixed conifer and spruce forest. In New Mexico, A. gooddingii can be found at Gilia and Lincoln National Forest. However, over 95% of A. gooddingii populations and their habitats have been heavily burned by wildfires since 2006 (Roth 2020). As a result of the wildfires, A. gooddingii is a Forest Sensitive Species and is listed as endangered species by the State of New Mexico (Roth 2020).

Allium gooddingii at Lincoln National Forest

On Lincoln National Forest, A. gooddingii can only be found at the Smokey Bear Ranger District at elevations above 10,000 feet. In recent years, large populations in the district have burned in two wildfires: the Little Bear Fire (2012) and Three Rivers Fire (2021). The Little Bear Fire burned a total of 44,330 acres in the Southern Sierra Blanca regions of LNF, including 80% of known A. gooddingii sites (Roth 2020). In addition, the Three Rivers Fire burned more than 7,000 acres of LNF, burning into the Little Bear burn scar. Both fires left the species’ habitat without any canopy cover.

With the loss of canopy cover, the long-persistent of these plants is questionable. Therefore, surveys are carried out to monitor the impacts of fire on A. gooddingii populations. Luckily, I had the opportunity to join the Wildlife Crew in my district and partake in the surveys over several days. The surveys entailed heading to different scouting points within areas that were either burned by the Little Bear, Three Rivers, or not burned at all. At each point, the number of A. gooddingii individuals were counted within a 10 meter radial plot.

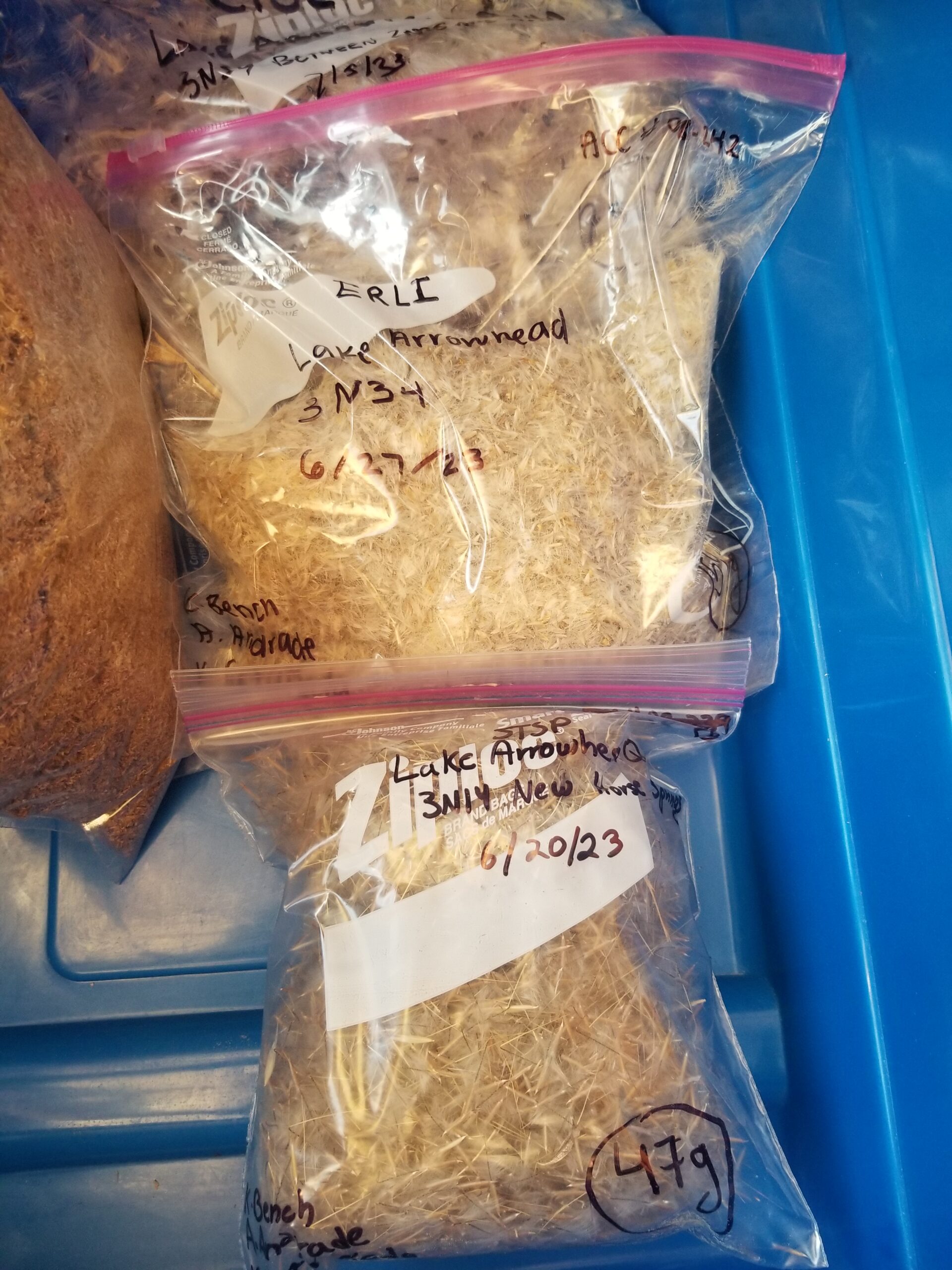

However, it was not an easy task getting to the different points. We had to hike down and up several steep slopes at an elevation of 11,000 feet to get to the points. Despite the challenging hikes, we completed all 16 scouting points. Later in the season, the Wildlife Crew will head back and collect seeds to be used for future restoration in LNF.

Pollinators

One of the most abundant populations I’ve seen at Three Rivers burn scar had several pollinators roaming around. I was able to capture a few.

Literature Cited

Roth, D. 2020. Status report. Goodding’s onion (Allium gooddingii). Gila and Lincoln National Forest, NM. Unpublished report prepared by the EMNRD-Forestry Division, Santa Fe, NM for the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, Region 2, Albuquerque, NM. http://www.emnrd.state.nm.us/SFD/ForestMgt/endangeredandrareplantreports.html