When I first set off for my time as a CLM intern, nestled in the middle of an Oregon forest, I expected a period of solitude and stillness. I thought everything would slow down and go quiet—a sharp contrast to the busyness of graduating college right before.

In some ways, that was true. We spent our days monitoring the phenology of our seed-bearing friends. I felt like I was moving with the slower, natural rhythm of Kairos time, purposefully noting each plant population as it moved through stages of growth: budding, blooming, ripening, and then fading, red and blue fruits growing only to shrink into white, crusty remnants, once bright flowers becoming brown and crispy. At the start of our season, I could scoop up the plethora of bees lying lazily in the flowers in the meadows, but I can’t find them anymore. A wasp that once dug into my soup and flew off with a bit of tomato pays my lunches no more visits. The dragonflies that danced around Fay Lake in the height of bloom and warmth are hard to find now; all that remains of their presence are shimmery fragments of discarded wings in the mud.

As someone accustomed to measuring time by deadlines, I always seemed to be counting down—whether to the end of a school year or a job that stressed me out. Time was very numerical. For once, I’m not anxiously awaiting the end of something. Time moves differently and too quickly now. Although I don’t feel that any moment went unappreciated or wasted, I still wish I could go back.

One reason I took this job was my interest in conservation agriculture and agroecology, even though my background is mostly in conventional horticulture and gardening. I wanted a position that exposed me more to the natural flow of things, and this internship has done just that. Unlike anything I’ve done before, this job felt like a partnership between the natural systems and us interns, not a battle. We gathered seeds from prolific plant populations, intending that the cleaned, prepared seeds will be spread across barren soils next season. (If this will actually happen, I’m not sure, considering that the U.S. Forest Service budget was cut and seasonal hiring has been suspended…) We’ve contributed to wildlife surveys, measured beaver dams and lodges, and caught insects in jars to identify them. One night, we even went in search of northern spotted owls. Driving forest roads at night, we’d stop, play owl calls over a radio, and wait for curious owls to call back and check us out to see what all the ruckus was about. IT WAS FIRE. We didn’t get off work until after midnight, but I had no trouble staying awake. We’ve attended meetings on timber production, went on a backpacking trip to map threatened and endemic species, and had a front-row seat to witnessing how all the elements of the forest work together.

But the solitude and calm I expected didn’t materialize. Chaos and camaraderie marked every day of this internship. We stayed busy with trips, nights out, hikes, and karaoke. Our months were filled with inconvenience: my car was broken into, Ash’s belongings were stolen, there was a hospital visit, and, of course, there was the heartbreak in the office when news broke about the USFS budget cuts that led to layoffs for our wildlife friends. And it’s not been quiet, either. We are in a constant dialogue with each other that for whatever reason involves singing more often than speaking.

This blog post feels personal, even though it’s meant to be about my job. But this job is personal. Every bit of knowledge I’ve gained, every plant we’ve worked with, is tied to memories. And now, as the season ends and our conversations turn to how quickly time has passed, I’m drenched in nostalgia, so forgive me! I’m a mess!

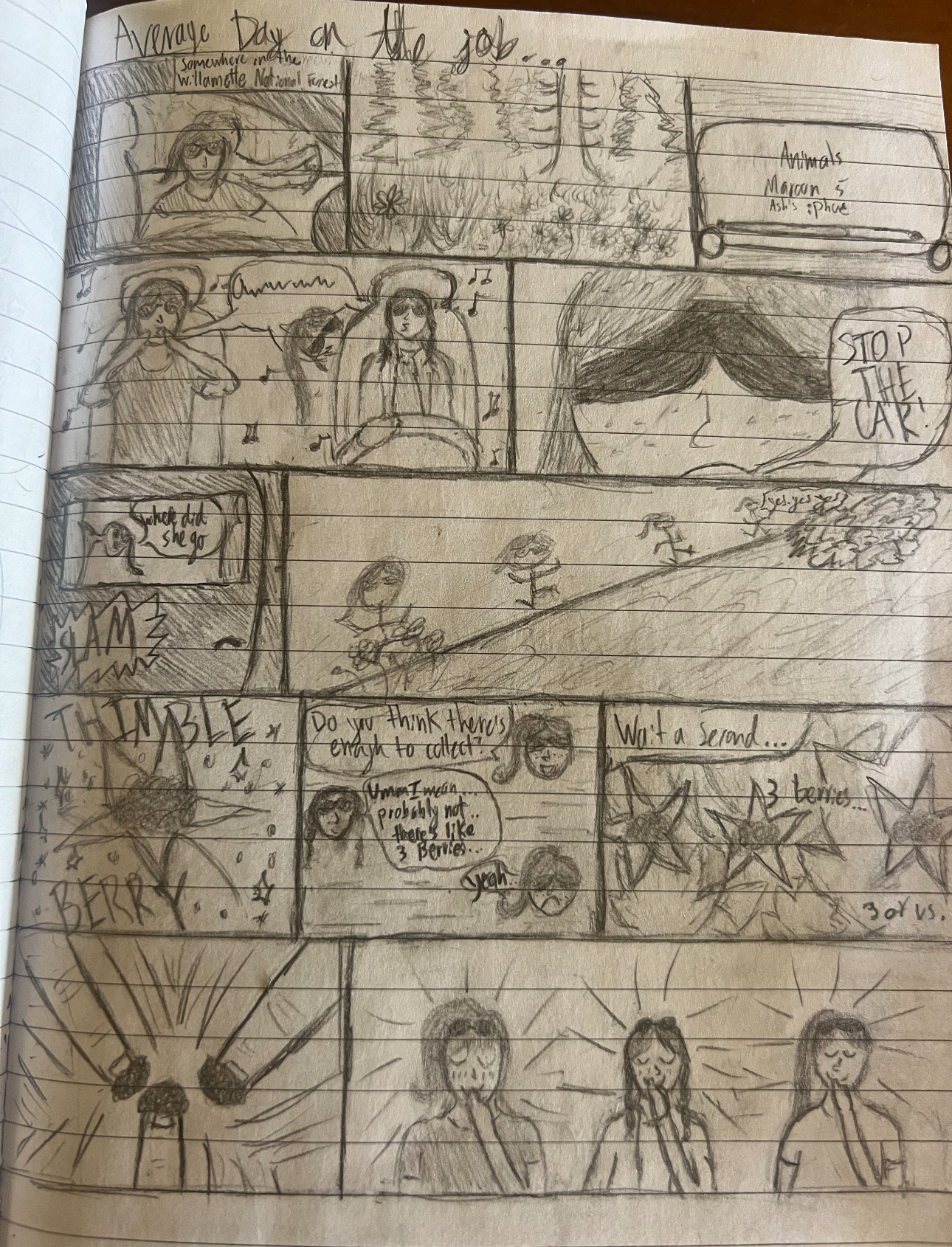

I see Scotch broom, Cytisus scoparius, and remember the spittlebugs that fascinated us when we first arrived. Thimbleberry isn’t just Rubus parviflorus; it’s Ash’s comic about our workday. Snowberry, Symphoricarpos mollis, is Ella crouched in a patch, trying to walk away after filling bag after bag, but unable to resist. Trillium is the retired forest botanist, Tom, racing up the mountain, leaving us struggling to keep up and desperate for a breath. Coneflower, Rudbeckia occidentalis, is Ash, unhurried and peacefully walking about a meadow in the cold rain. Penstemon is hiking down an old road, picking up fallen branches, and playing a game like the Japanese martial art, kendo. Mountain ash, Sorbus sitchensis, is rock skipping on Elk Lake. These plants exist and evolve alongside us, not despite us.

As remarkable as the program itself has been, I’d be lying if I said the best part of it all was anything other than Ash and Ella. I’ve never spent as much time with two people as I have with them over these past several months. I’m so grateful they were my co-interns, and I’m hopeful we’ll reunite someday! But for now, it’s time to return to Texas. Then, come January, I’ll head to New Zealand—new plants and, hopefully, new friends await.

Crying, screaming, throwing up.