” There’s something especially beautiful about holding a critically endangered bumble bee in the palm of your hand whilst knowing that you’ve dedicated a whole summer of your life to collecting plant seed that will be used to create more habitat for this species “

August has been a busy month that threw us quickly into long days of seed collecting. After spending most of the beginning half of the summer preforming vegetation surveys with the botany crew, my CLM coworker Grace and I started our solo mission of collecting and scouting as many populations of our target plant species as we could.

The first week of the month we only had one species that was seeding and ready to collect, Heuchera cylindrica (roundleaf alumroot). By the end of the month we were collecting from 6 different species adding Agastache urticifolia (giant horse mint), Chamerion angustifolium (fireweed), Erigeron speciosus (showy fleabane), Heterotheca villosa (hairy goldenaster) and Monarda fistulosa (wild bergamot). Some of our target species were not ready to collect yet and will not be seeding for several more weeks.

It’s been fascinating to have the opportunity to closely observe the phenology of each species. Even more interesting has been the diversity of phenology within the same species, same population, or even the same plant!

We quickly learned that phenology is not so predictable. Flower heads hang around longer than you would expect, the transition from fruit to mature seed a lot longer process. Towards the end of the month we became better at giving plants more time, instead of driving back to the same population multiple times (though it still happened).

An interesting observation I made this month is that when flowers are going to seed, the seeding begins at the based of the inflorescence and moves up, or at the center of a flower head and moves out. Some species you can observe this really well, like in Chamerion angustifolium, towards the end of the summer when it begins to seed, it will have fluffy white seed pods breaking open towards the bottom of the spike, but on the top there will still be flowers!

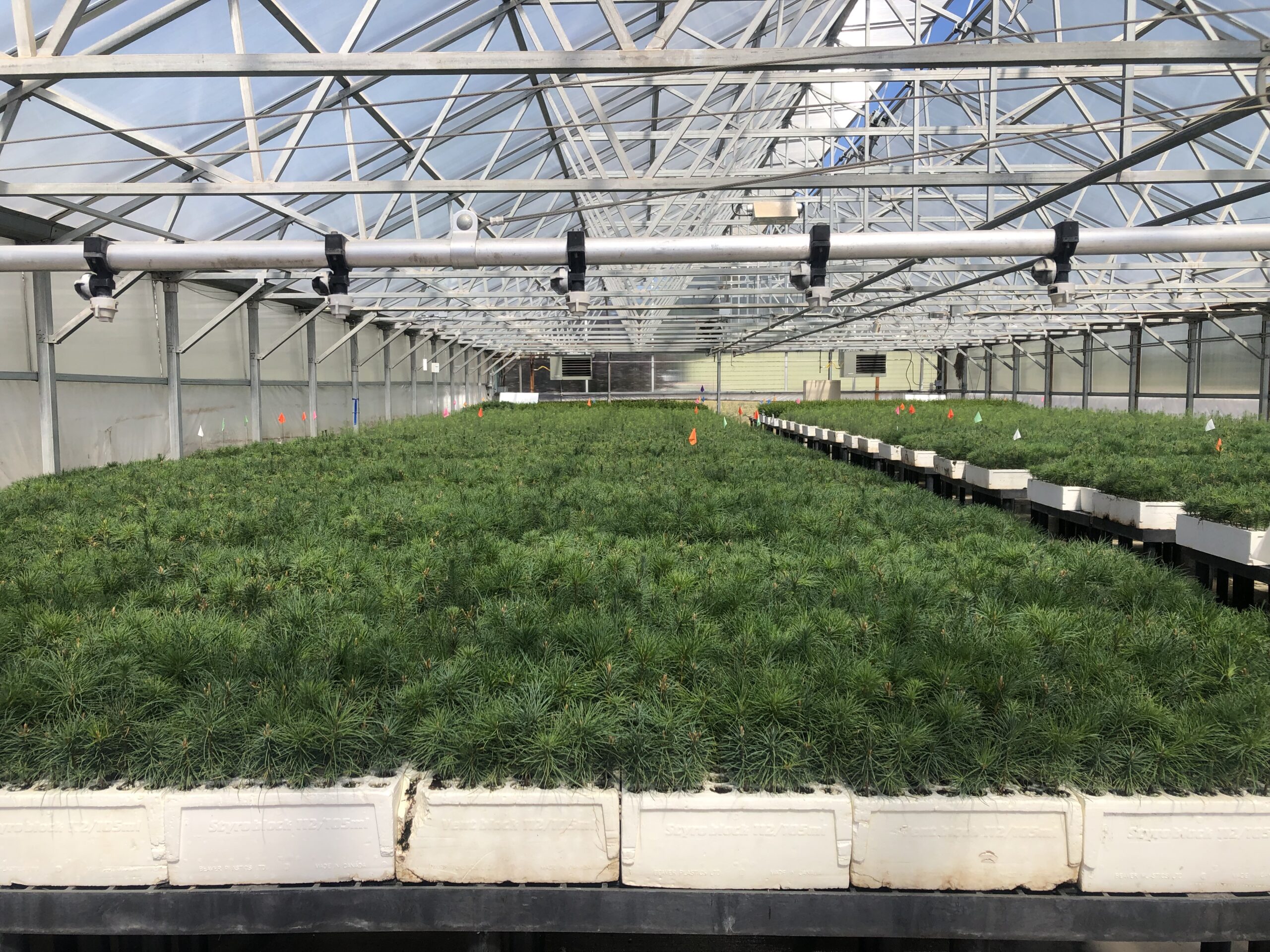

In addition to collecting lots and lots of seed, we got the amazing opportunity to get a tour of the Forest Service Nursey in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho where we will deliver our seed at the end of the season. I was very grateful that we got to visit it in to the middle of growing season to see all the plants that they grow for restoration and research projects. While the nursery does grow herbaceous plants for seed planting, they mostly grow coniferous tree saplings and send them out as plugs to be planted back in the National Forest after logging or burns. I’ve never seen so many tree sapling in my life!

The highlight of the tour was getting to learn about all of the whitebark pine restoration efforts that the nursery plays a key part in. The whitebark pine, Pinus albicaulis, was added to the Endangered Species List as a “Threatened” species in 2023 due to insects, fungi, and climate change causing the species to decline rapidly. The main concern is blister rust which is caused by a fungus. However, it has been found that there are populations of Pinus albicaulis that are immune to the disease! These trees are known as Plus Trees. Researchers and FS crews alike have gone up to these populations and gathered seed and pollen so that Plus Trees could be grown at nurseries and then planted back into suitable habitat!

The manager of the nursery said that the hardest part of growing the Pinus albicaulis is that they are built for harsh high elevation growing conditions which means they grow slowwwww. In the first year, they may only grow an inch out of the soil!

We were lucky enough to hike up to one of these Plus Tree habitats. Pinus albicaulis sure knows how to pick a beautiful spot.

Another highlight of the month was getting to do our final pollinator survey. The whole crew journeyed to a meadow Grace and I had scouted for seed collecting and recorded over 60 bumble bees! The morning was a little chilly in the mountains so the bees were cold and sleepy and absolutely adorable.

Preforming these bumble bee surveys means a lot to me because they remind me why all the seed I’m running around collecting is so important. During this survey in particular we believe that we found two Suckley Cuckoo Bumble Bees (Bombus suckleyi) which is a native species of concern and considered rare in the state. There’s something especially beautiful about holding a critically endangered bumble bee in the palm of your hand whilst knowing that you’ve dedicated a whole summer of your life to collecting plant seed that will be used to create more habitat for this species.

– Erynn

Flathead National Forest, MT