As the frost becomes more frequent in the Chugach, October is filled with bittersweet moments as the season ends. Our final seed collection excursions had an underlying mournfulness. Seeing the fruits (I suppose they’re seeds) of my labor as bags full of seeds after processing and cleaning filled my heart with satisfaction and fulfillment. With that fulfillment came a twinge of sadness, knowing that the season was over and my days romping around the wilderness with my field partner were gone. The end of the season also came with the excitement of fall seed sowing. I delivered seeds to the Anchorage Water and Soil Conservation District for grow out several times, and we got to direct sow Artemisia arctica, Angelica lucida, Heracleum maximum, and Calamagrostis canadensis at the Resurrection Creek restoration site. Through this process, I witnessed how my work this field season will directly impact my home state and the restoration of its natural spaces. (and it was fun!)

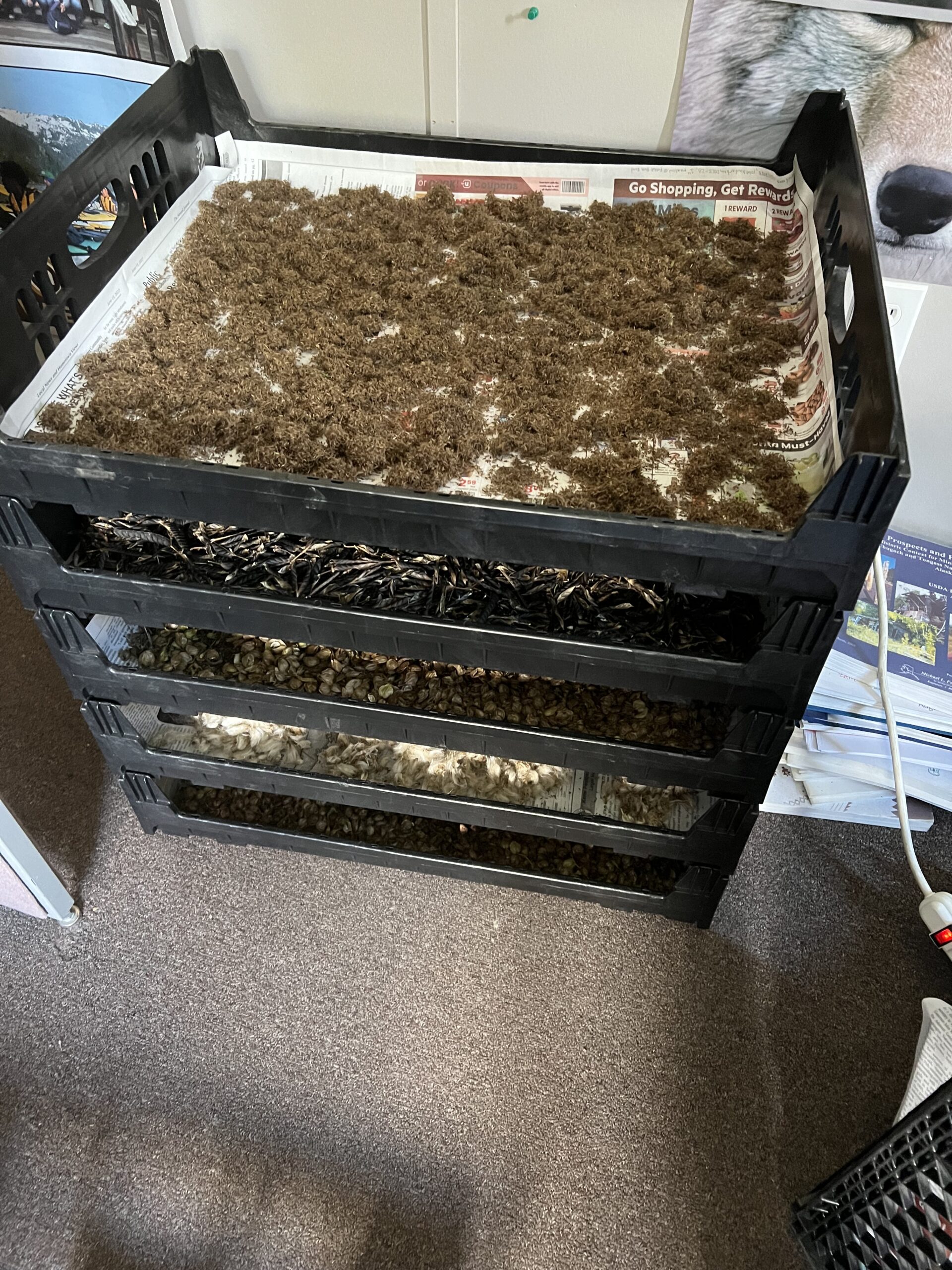

By October, we had harvested most of the species on our target species list, but there was one that I couldn’t let evade me: Artemisia tilesii. I noticed significant patches when I scouted for fish with a friend in the Anchorage area on the Bureau of Land Management and Municipality of Anchorage parkland. I had also noticed some at the Anchorage Botanical Garden growing in their wild spaces while on a date (the native plant obsession never pauses, even on a date.) So, I contacted The Bureau of Land Management, the Municipality of Anchorage, and the Anchorage Botanical Garden to gain permission to harvest on their land. All organizations obliged, letters of agreement were drawn, and my field partner and I got to travel to Anchorage for a tilesii collection. Our efforts seemed in vain when I set out to clean the seed during one of my last weeks, though, as they were infested with some weird, goopy sacks we deemed the “Goopy bois.” My mentor researched the mysterious “goopy bois” and discovered they were Trypeta flaveola (fruit fly) eggs. Although they aren’t considered especially harmful pests for the plants, we hesitated to send the infected seed to our grower. I spent hours brainstorming and experimenting with ways to clean the seed from these eggs. Finally, I found a sieve sufficient to separate the two post-cleaning with our mechanical seed cleaner, the “Clipper Office Tester.” Once most eggs were separated, I plucked the rest out with tweezers. Finally, I had my pure collection of Artemisia tilesii seeds ready to grow out for the restoration site.

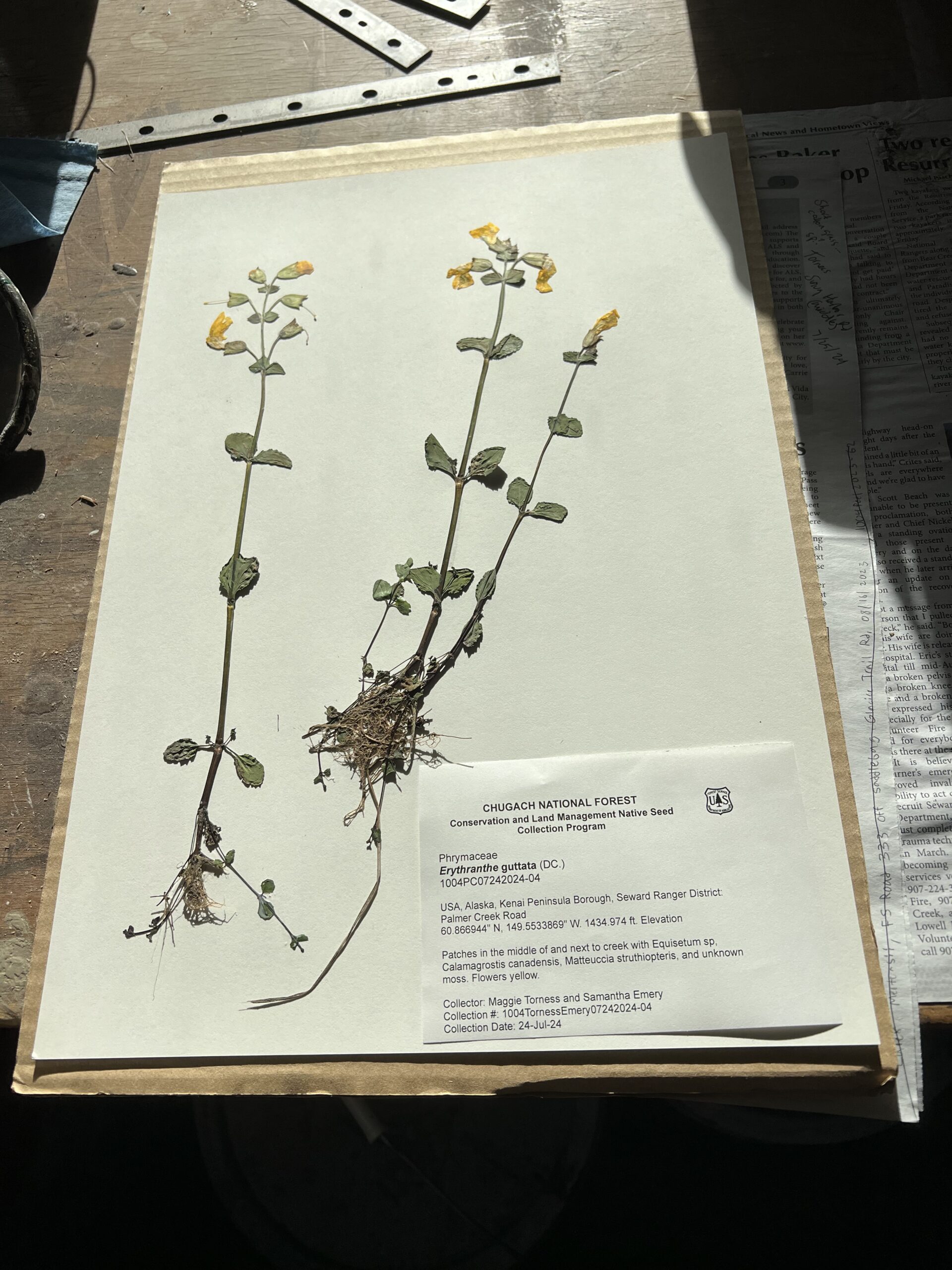

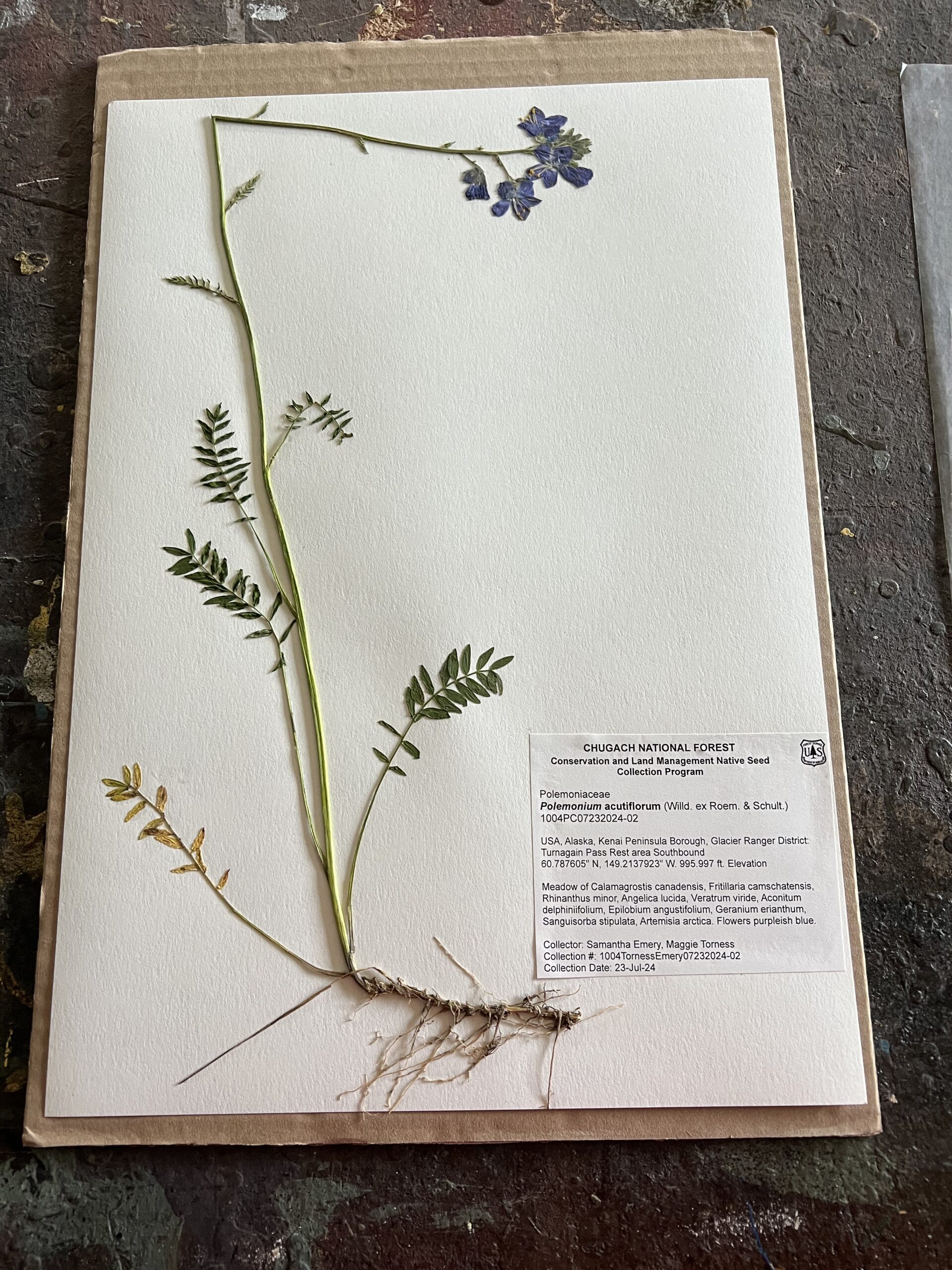

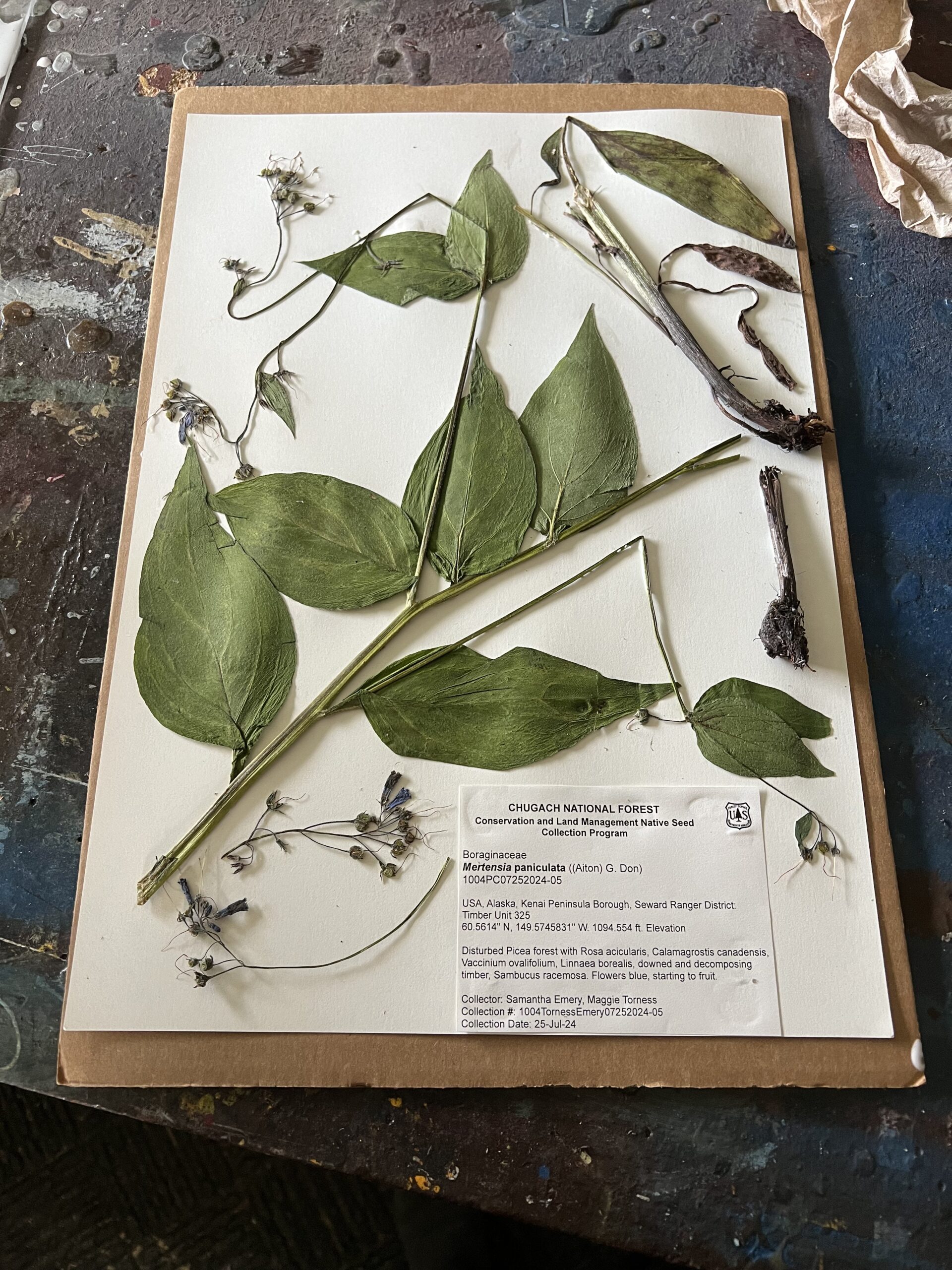

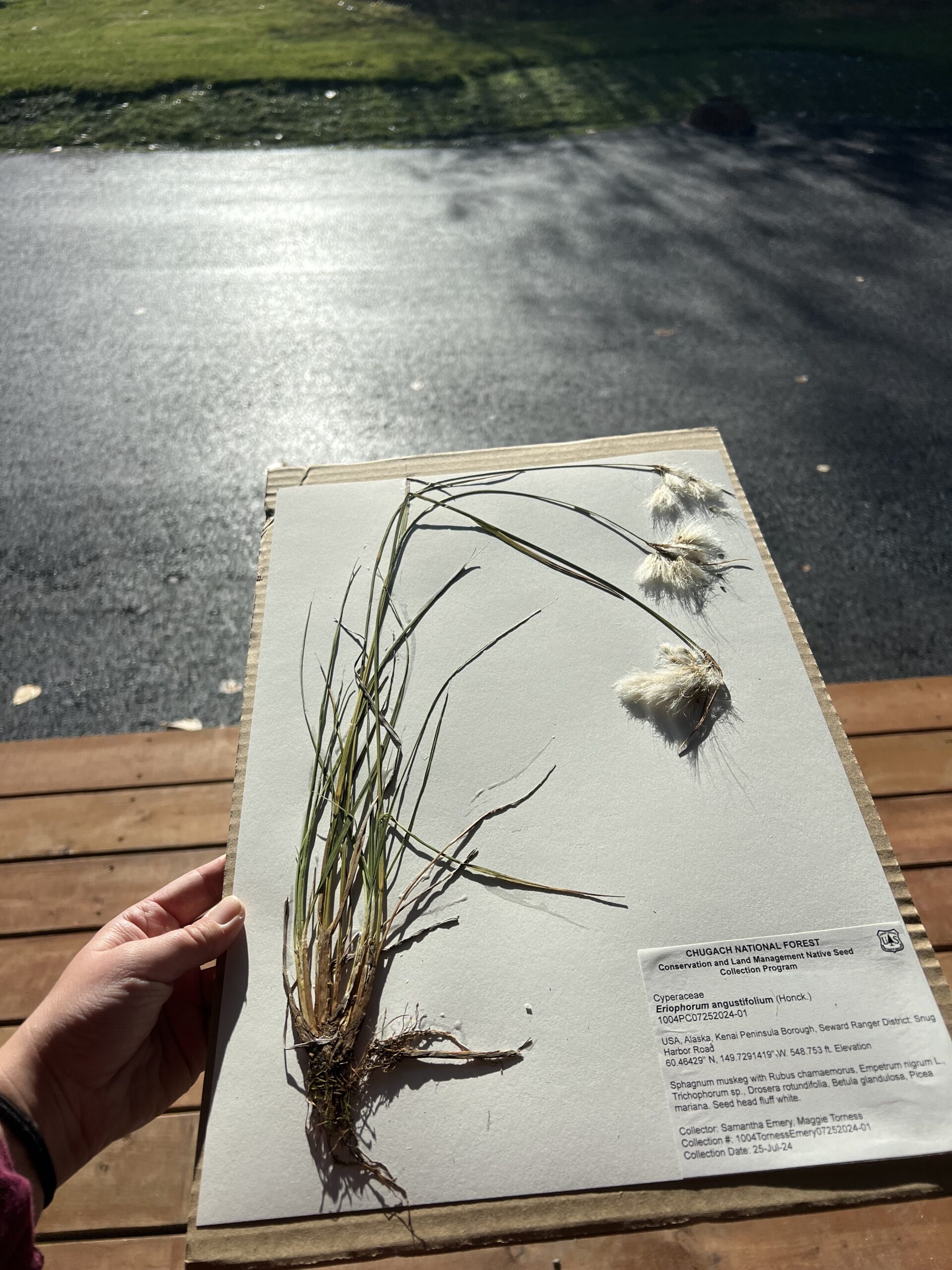

An exciting part of the end of the season was mounting our herbarium vouchers. We had carefully and meticulously arranged plants for pressing all season long and finally got to create the final product. Creating the labels came with some headaches, as most data organization tends to, but it resulted in satisfying and beautiful labels for our vouchers. I had never mounted a voucher before this; my closest experience was pressing flowers to glue on construction paper for arts and crafts as a child. It turns out mounting vouchers is essentially the same thing: doing so more mindfully! I found immense joy in mounting the vouchers, even the pesky long, delicate, and abundant graminoids. Each voucher came out like a work of art. Thankfully, my work with vouchers didn’t have to end there. I had two weeks left after my field partner’s season ended because I came to the forest later. Because of this, I got to work on a project I was excited about after tying up all the loose ends from seed collection the week after her departure. My last week was cataloging herbarium vouchers from the Chugach National Forest Herbarium. There are thousands of specimens and no records compiling all of their data. I started the cataloging process by visiting the Herbarium and entering the data for as many specimens as possible. To some, that might sound like a snooze, but for me, there was no better way to cap off the season than to look at plant specimens from 1964 to now and aid in their immortalization by recording their data. (Also, how cool is it that collections I made will be stored for future botanists to reference?!)

It’s challenging to express the depth of my gratitude for this internship and the realization of many of my aspirations. The dream of being a scientist, the dream of working in a National Forest, the dream of contributing to the restoration of natural spaces in my home, and the dream of continuing the native plant legacy in my family – these aspirations have been realized. I went on excursions to monitor wildlife, maintain bird nesting boxes, hike and explore almost daily, harvest native seeds, spread native seeds, and collaborate with other botanists on native seed collection and restoration from different organizations. This experience allowed me to connect with people who share my love for the natural world, and through all of this, I was able to nourish my soul.

This opportunity has transformed me from a native plant enthusiast to a full-on botany nerd. Before this position, I enjoyed foraging for berries and a few native plant species greens, but I never imagined I would memorize the Latin names of so many species. Now, I find myself knowing some species only by their scientific names, most by several common names and their scientific names. As I stroll through nature, I mutter the names of the plants around me and eagerly share the information I’ve gathered this summer with anyone who is with me (and willing to listen.) This behavior might not be entirely new for me, as I spent years guiding at a remote lodge and created a plant tour on a muskeg full of ethnobotanical facts. However, now, the information I get to share is far more in-depth and spread across a plethora of new species. The joy of sharing this knowledge is as fulfilling as the knowledge itself. Before this experience, I was still determining my career path. I knew I wanted to work in ecology, but I wasn’t sure if I wanted to focus more on wildlife or botany. Now, I know that botany is the route I would love to pursue. Part of me wishes this was a permanent position and that I could explore the wilderness and harvest native seeds every field season, but I know that future CLM interns will have life-changing experiences like mine, and I am so excited for them to experience it. I was nervous at the beginning of this season, knowing I had no formal botany education, but passion and curiosity quickly propelled me to gain the knowledge I needed not only to succeed but to flourish in this position.