How has it been over a month already? I have no idea. Time flies when you’re getting settled into a new place, a new job, and have so much exploring to do outside of work, too!

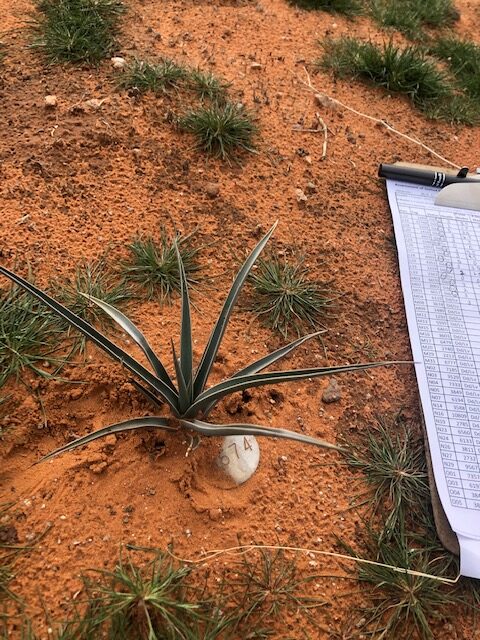

The past few weeks have had a heavy focus on data entry. We’ve needed to enter our records from the assessments we do at the gardens each month that rate the health status (1-3) and herbivory severity (1-5), as well as record the number of live blades each plant has, number of dead blades, and any notes.

At the Cactus Mine and Ridgecrest gardens, the assessment doesn’t take very long between Bridget and I because many of the plants didn’t survive – there are only 23 seedlings still alive at Cactus Mine and 20 at Ridgecrest. Meanwhile, the Utah garden has a whopping 284 seedlings that are alive and —for the most part—well! This does mean a lot more crouching or kneeling, back up to standing, then shifting over to the next plant, and back down again, for Bridget and I as we assess about 140 plants each! Although it’s more uncomfortable for a longer period, it’s exciting to have one of the gardens flourishing! We are thinking the trees are doing so well here because it gets the most rain and is also the coolest out of the three. At the other end of the spectrum, Ridgecrest is the hottest and driest.

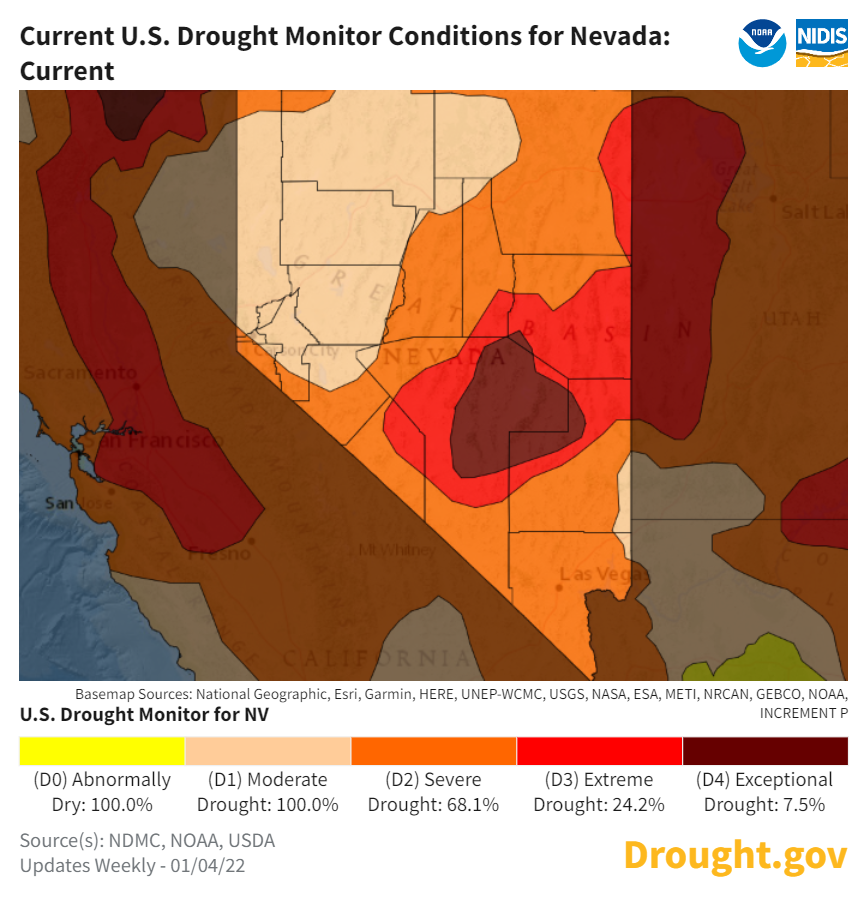

Joshua Tree seeds have evolved to rely upon rains to germinate, which makes sense why the wettest garden would be performing the best. Unfortunately, looking at current and predicted climate trends, this is concerning because these rains that the Joshua Trees depend on to create new generations are not happening as often. Nevada officially declared a drought in 2002 that has continued to current times. Drought.gov provides information on current and historical (since 2000) drought conditions: currently, 68.1% of Nevada is in a severe drought, 24.2% is in extreme drought, and 7.5% is classified as exceptional drought.

Coming from a place of excess water, the idea of droughts and declining water source levels scares me. Along with this comes frustration that we are not doing enough to reduce water usage. At the individual level, around Las Vegas/Henderson/Boulder City, some houses have grass-covered lawns –one right outside of work even has sprinklers spraying their grass. It would be much better if they planted more native desert species and removed water-consuming grass. At the industry level, resorts use a lot of water mostly from hotel guests, who use more than 63 gallons per day on average, according to this article by Sam Bruketta, 2020. Although many resorts have been working to reduce water usage, such as MGM Resorts, which has reduced water use by 25% since 2007 (Bruketta, 2020). However, a truly unnecessary use of water is the Bellagio Resort fountains, which have been scrutinized for losing about 12 million gallons per year from evaporation (Bruketta, 2020). A different type of industry, is one of the biggest sinks of water, from watering grass on a larger scale than the individual homes mentioned earlier: golf courses. According to the Las Vegas Water District website, golf courses in Southern Nevada use an average of 725 acre-feet per year. My brain has a hard time imagining what this means… The Water Education Foundation website states that one acre-foot is approximately 326,000 gallons of water, and would cover one football field in a foot of water. So, for a visual of what an average Las Vegas golf course would use in a year, it would be enough to fill a 725 foot deep, football field-sized swimming pool! That is an insane amount of water.

The site also mentions that California households use about ½ – 1 acre-feet of water on average per year: about 163,000-326,000 gallons of water per year, each. That estimate brought my thoughts to the lifestyle I had this summer while living in a dry cabin in the woods of Alaska where I was working at the time. I’d never heard of a dry cabin before starting my housing search, but it was the cheapest option —for good reason— because they are cabins without running water, which means no toilet, no shower, no faucets of any kind. I was scared to live like that for three months having never been in a situation like that (besides short term circumstances when camping out for a few days). However, it made me realize how much water I use and waste under normal circumstances with the luxury of indoor plumbing —leaving the water running while washing hands, doing dishes, taking showers, or even flushing the toilet— everything!

How the water situation worked in a dry cabin, was we had two clear, five-gallon jugs that we’d fill up at the water-filling station in town, and set up on the counter over the sink which drained into a five-gallon bucket that we’d dump outside. And unfortunately, we did have a few times when we didn’t realize the bucket was nearly full, and spilled over some foul smelling water with chunky food bits/oily residue onto the floor as we scooted it out from under the counter to dump… Aside from those “oh crap” moments, overall, living in a dry cabin really wasn’t so bad!

With the goal being to take as few trips as possible to the water filling station; using as little water as possible to wash hands, do dishes etc. was the primary way to achieve this. We were so careful to reuse water when possible and use the bare minimum amount we could to get the job done. Although I dreaded the idea of living in a dry cabin at first, I’m so glad I had that experience to teach me so much about conserving water, which I’ve tried to hold with me since then. It makes me wonder if everyone lived like that for even one week, what difference it could make on our water usage overall in the US, especially in dry regions like this, where we need to be doing more.