This last month has been a month of office work, a month of underground buds, and a month of buds (friends).

We’ve mowed the prairie once again. We mow several of the plots at our sites to simulate cows’ grazing, but in order to know how much biomass has been removed from the plots we go in with scissors and manually cut the plants and sort by functional group. The plants are then dried and weighed. Mowing and snipping the grasslands is maybe the most ridiculous thing I’ve done. We’re going to go back in a few weeks to re-trim the grass, to see how much it has grown in the time after the mowing. Science is pretty silly sometimes.

The Rocky Mountain Research Station in Rapid City, South Dakota is kept at a chill temperature that nobody seems to have control over. This means that even when it’s 95 degrees out, I still have to bring a sweater to work when I’m in the office. I’ve been doing a lot of sorting and weighing of plants, plus mind-numbing data entry.

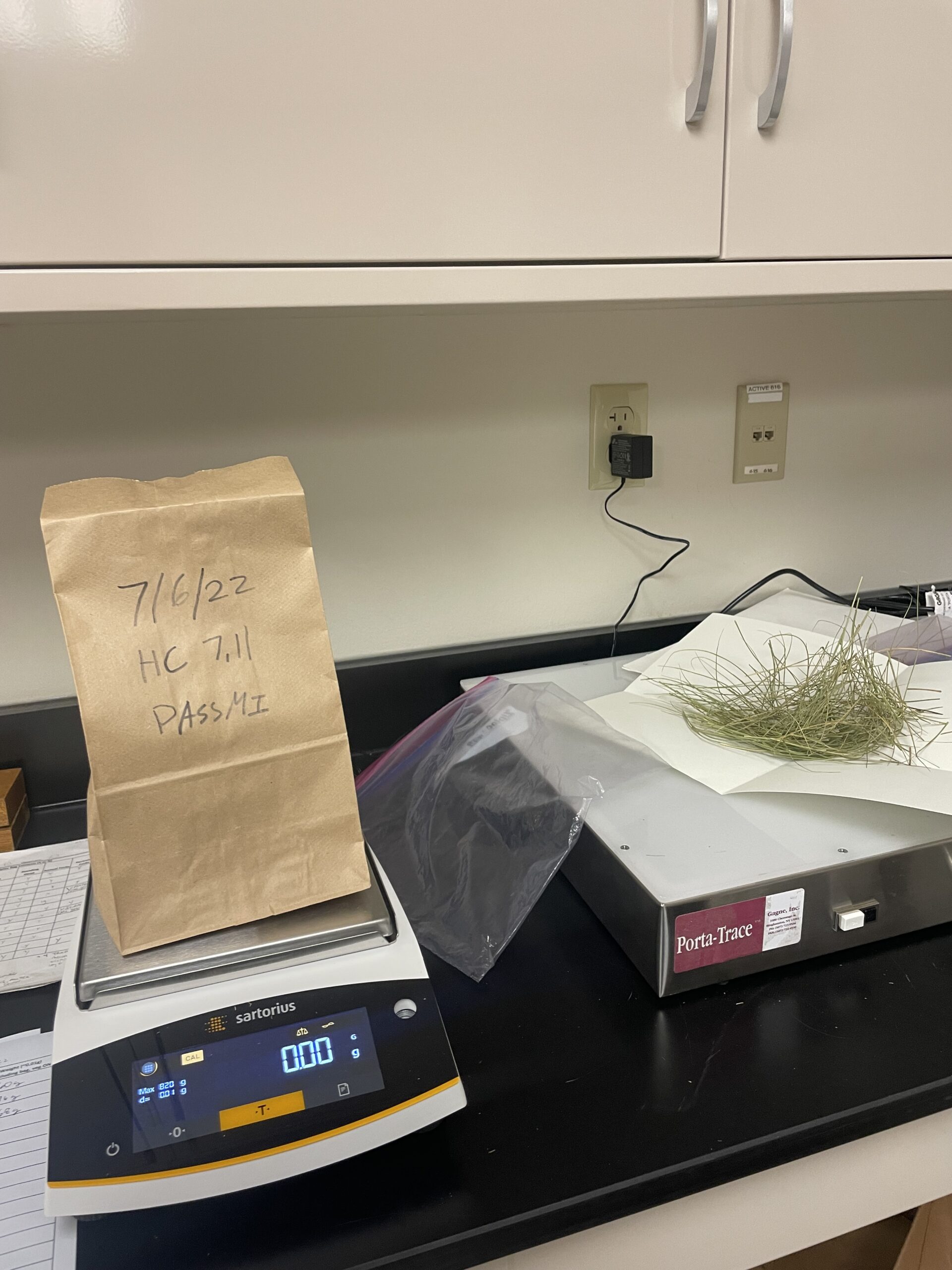

The process of weighing the dried plants involves shaking everything out of its paper bag onto a sheet of repurposed herbarium paper, placing the bag on the scale and zeroing it, finagling everything off of the herbarium paper back into the paper bag, then weighing and recording the mass. We’re about halfway through the job: there’s two sites, each which had about 50 plots clipped, and each plot has up to eight paper bags. These eight bags are categorized by their contents: annual forb, perennial forb, warm-season grass, cool-season grass, annual grass, standing dead, Bouteloua gracilis/Bouteloua dactyloides, and Pascopyrum smithii.

Besides snipping and weighing grass, my supervisor, Jackie, also does research involving underground buds, typically grass buds. She studies the bud bank and how plants regenerate from belowground buds throughout their life histories but also after events like fires. Some of this research is done out of Colorado State University, and in the middle of the team’s fire treatment a burn ban was put into effect in Fort Collins. They drove 6 hours to Rapid City to burn the samples and I got to be involved with the use of fire tables!

Fire is super interesting to me. Experiencing the near-annual smoke season in the Pacific Northwest, I’ve heard about how the bigger, hotter fires of today are the result of forest mismanagement and practicing fire suppression. It feels weird to be preached at by Smokey Bear that only I can prevent forest fires when fires have been present in forests since time immemorial. I’ve also known that prairies also rely on fires to “refresh” the vegetation but I’ve never considered how it all works. It makes sense: perhaps fireweed responds to fire so well because its rhizomes are just deep enough to not crisp up in a fire and the burning of neighboring plants opens up aboveground space for its buds to shoot up and bloom.

Jackie took Myesa and me down to Colorado State University in Fort Collins to teach us how to dissect and count the underground buds of some of the native prairie plants. It was a lot of tearing grass apart under a microscope, trying to determine if the bud was, in fact, a bud or if it has become a juvenile tiller. As far as I understand, the distinction is that a bud is completely underneath the prophyll (a sort of casing that protects it) whereas tillers extend past the prophyll. Even after spending a whole afternoon peering through the microscope, I still struggle when distinguishing the roots from the buds.

Outside of work, I’ve done lots of playing. There’s some pretty good hikes here, and a few weekends ago I got up at 3 am to get a sunrise hike in, despite a thunderstorm that lit up the lawn outside as I sipped my coffee. The weather cleared up just in time for my friends and I to hike up Little Devil’s Tower to see the sun come up over Rapid City. I’ve also had two buddies visit me: my partner, Bryce, from Tacoma and my best bud, Joe, from Chicago.

The Black Hills have been an excellent place for me to get into outdoor rock climbing and it was exciting to share that experience with some visitors. The Black Hills granite will tear your fingers apart and rip your skin open without you noticing, but it is also super grippy and relatively easy to climb. The local climbing community is pretty small and tight, and there’s a huge amount of climbing which attracts people from all over to climb in the Hills.

When Joe visited, we toured one of the numerous caves out here. We went to Jewel Cave, which is named for the calcite dogtooth spar found within. Jewel Cave is the third-longest cave in the world, which is pretty neat. Southeast of Jewel Cave is Wind Cave National Park, and while I haven’t been inside Wind Cave itself, I have gone through the park several times to see the bison and prairie dogs.

A few weeks ago I helped do some point intercept line transects at Wind Cave. Point intercept line transects involve placing a pole, the “plunker”, down along a transect tape at regular intervals and recording which species are touching the plunker and at what heights they are touching it. This was fun because point intercept involves less species analysis than taking aerial cover of 1 meter x 0.5 meter quadrats, which is what most of my summer’s prior data collection has been. Plus, most of the transects were through bare prairie dog towns so there wasn’t any data to record.

Soon enough, I’ll be back out on Buffalo Gap National Grassland, trimming the prairie by hand once again.