It’s the end of August and the grasslands have faded into a flat brown. The graph of the soil moisture probe trends definitively downward towards dryness. The cows have always been present out here, but I think I’ve been noticing them and the bison more. At our site by the Badlands there’s finally cows grazing the pasture and more than once the herd has curiously surrounded the exclosure I’m working in. I saw several RVs parked on Buffalo Gap National Grassland, surrounded by cows and I wonder about the campers’ reactions as they woke up to the sounds of cows all around them.

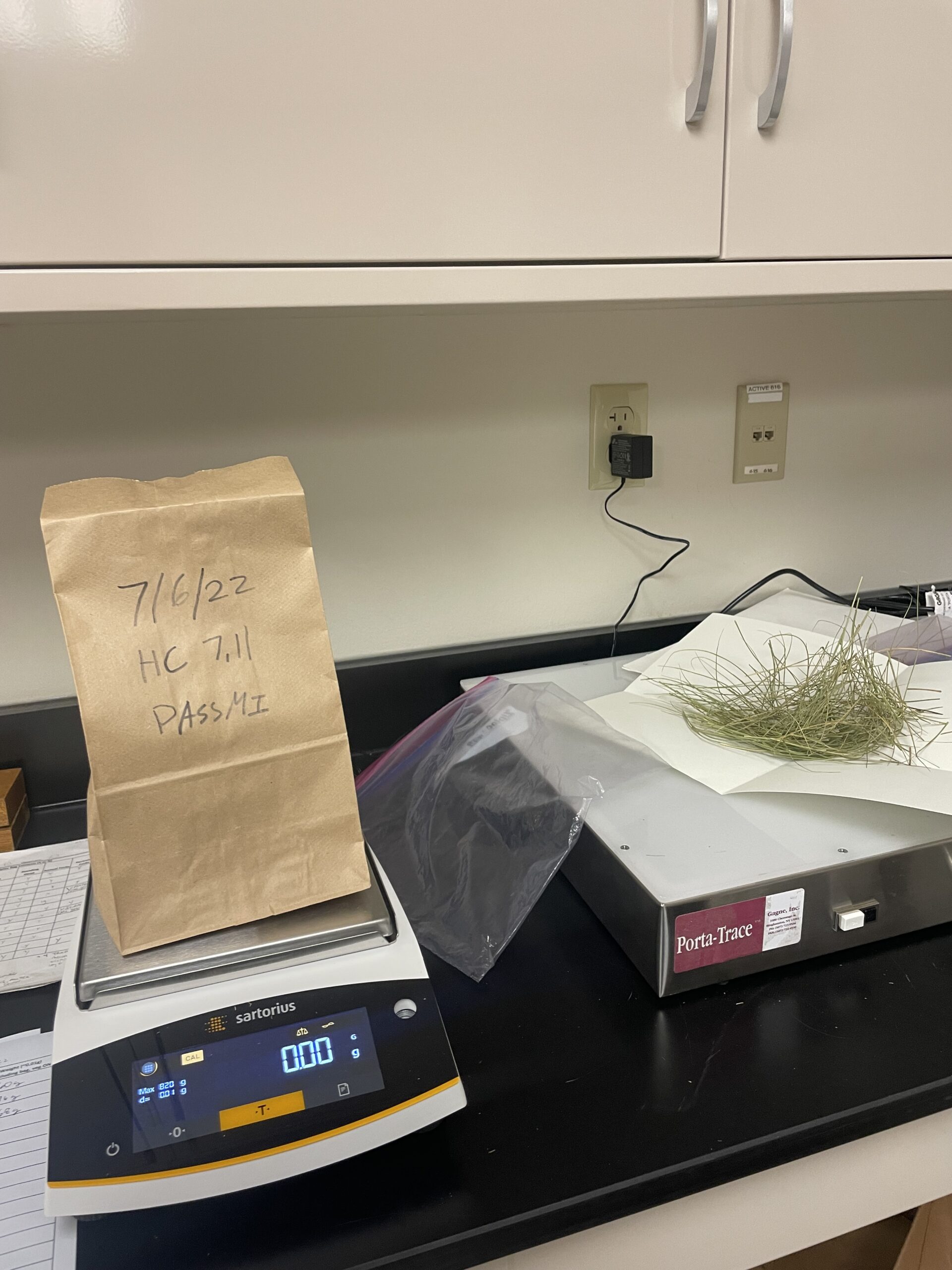

The past three weeks have included some relatively backbreaking work: clipping and sorting. Some of the grasses are sorted out by species, but most are put into the broader categories of their functional groups, warm season versus cool season.The last batch of plots we’ve been clipping are 20 cm x 1 m and were mowed in July. Some of the grasses have grown back but many are just short, brown stalks. Without ligules and mostly without hairs, these stems are identified by vibes more than anything else. It’s been difficult to trust my intuition.

The nice thing about the clipping is that it is a job that cannot be rushed. Quick work is shoddy work, and shoddy work is simply not worth doing. The first week or two of clipping was relaxing because I could catch up on podcasts and just take my time snipping away at grass, enjoying the dull roar of grasshoppers and meadowlarks. By the third week, I was exhausted. My neck and legs hurt from sitting in the grass for 30 hours a week and the insects left my ears ringing.

My internship is wrapping up next week and I’m sad to leave. The team I’ve worked with has been up to four people but mostly just Myesa and me. Working with a small crew is nice when you all get along and I’ve definitely made some lasting relationships here.

I’ve been super busy this whole summer: my weekends have never been so full. Yet, I know I still haven’t done all of the things Rapid City has to offer and I’m finding myself wishing I’d had done more, wishing that I did go to the Sturgis rally because hey, why not? I’ve been able to do so much: I’ve spent endless hours climbing around Rushmore; I’ve backpacked in Badlands National Park; I climbed a 13,000-foot peak in the Bighorns. I was half-expecting I’d have a lonely summer, living all alone in the four-bedroom Forest Service housing in Hill City but I’ve been able to have a very full experience.

I heard on the radio that the price of beef has gone down. Cows are getting slaughtered due to ranchers not being able to water them adequately in the drought; beef prices will go up in following years due to ranchers having smaller herds. Jackie likes to have her science directly benefit the shareholders: the local ranchers. I spent my summer looking at the cows’ food and how drought will impact the grasslands and while I may have been merely cutting grass by hand, it is nice to know that the project I broke my back stooping over is researching the effects of climate change.

I’ve learned a lot about grasses and grasslands and cattle and rocks this summer, but I feel like the most affirming lesson I received is that people are so willing to be of help. I’ve made a lot of great friends and have had a lot of excellent teachers, from Jackie being the most understanding and kind boss I could ask for to learning and nerding out about flowers with Myesa to my climbing friends, who have been sources of unwavering encouragement. After this summer, I’m heading back to Washington state, where I will likely continue to feel lost in life. However, it’s encouraging to know that no matter where I end up, I’ll have somebody, somewhere, on my side.