Hello Everyone,

I confess that it has been awhile since my last post, so you will have to forgive my absence. Part of my excuse is that in December I was able to take a three week break from my CLM position and go back home to northern Illinois for Christmas. I expected that the trip home would give me just a taste of a real winter with snow and ice. Well, it was fairly cold in Illinois, but for those three weeks in December it snowed more here in Needles than it did in Chicago! I did not see a single snowflake up north, and I missed the first snowstorm to hit Needles in more than 50 years! Now that I’m back in Needles I might be tempted to complain that I miss seeing at least a little bit of snow, but then I walk outside and realize that it’s 70 degrees in January, and I feel pretty good about life.

My CLM internship has been extended again, so that means that I’ll get to stay here in Needles until May, which will give me a full year in the Mojave Desert. That is great for me, and I am especially looking forward to being here for the spring and the possibility of some spectacular spring-blooming plants (but we need to get enough rain this winter – so I’m crossing my fingers). So far in January I’ve spent most of my time here at the office working on research and planning to establish long-term vegetation monitoring plots in our field office in the spring.

Since I haven’t been out in the field much since early December, I don’t have any new pictures or discoveries to share with you. So instead I’ll pull out some old pictures from the fall and we can look at one of the most distinctive desert plants here: ocotillo.

This is Fouquieria splendens (ocotillo). You can see that this one doesn’t have any leaves at the moment, and that is how these plants spend much of their year.

Fouquieria splendens, the ocotillo or coachwhip, is a bizarre plant. It is a woody shrub, with dozens of long, slender stems that branch at the base of the plant and then extend vertically straight up into the air or in a spreading arch. The plants can be up to 20 feet tall, and dominate the landscape in the broad valleys where they grow south of Needles. The stems are grayish-green with fissured bark, and are densely covered with long spines up to 4 cm long. Ocotillos are leafless for much of the year, a behavior that conserves water during dry periods.

Here’s a close up of one of those leafless branches. Those are some very sturdy, serious spines. Good luck climbing this plant.

When I first arrived in May, the large fields of these bare, thorny plants gave a particularly harsh and intimidating face to the desert. But their character changed dramatically after we were hit by the first summer rainstorm. Just three days after it rained, the ocotillos had produced a dense covering of lush green leaves. These plants, which had previously appeared gray and inescapably dry, transformed almost overnight into vibrant green spots of life against the bleak desert landscape. After a couple months and a dry spell the ocotillos dropped their leaves, and have returned to their formidable dry season appearance.

When rain does show up, ocotillo produces a high density of leaves in a hurry. They need to take advantage of their chance to photosynthesize while they have the water resources to do it.

Here’s a little perspective for you. I’m 6’3”. So we’re talking about a pretty substantial plant here. They can grow up to 20 feet tall. And they are especially striking because most of the other plants that grow around them are low-growing species.

I have yet to see the ocotillos blooming, but when the time comes this spring their flowers will add another splash of color to these plants. They produce dense spikes of bright red flowers high up on their stems. Hopefully I’ll be able to get a good look at some in a couple months, and I’ll share pictures with you (but they would also be worth looking up on your own right now). Ocotillo nectar is an especially important food source for hummingbirds as the birds migrate north in the spring. Of the desert flowers that hummingbirds use for food on their migration routes, ocotillos may be the only one that will produce nectar reliably even in very dry years. The birds require this dependable food source to give them the energy to make their long migrations.

I have not yet seen flowers or seeds from ocotillo, but you can still see some of the leftover structures. In the spring, those stalks will be full of brilliantly red flowers.

I haven’t seen very many of these, but here is a little baby ocotillo. Is it cute? Sure. Charming? Absolutely. Huggable? Not so much.

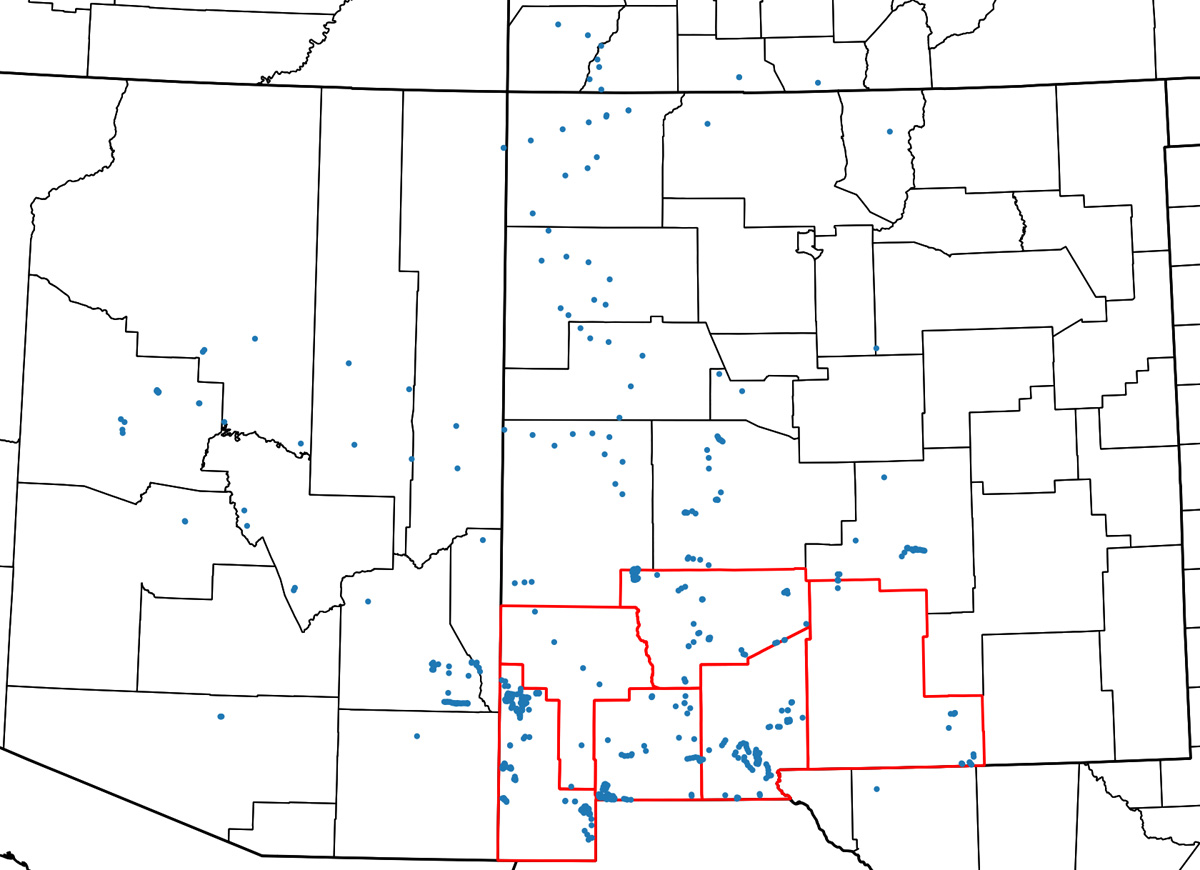

Ocotillos are a Sonoran and Chihuahuan Desert species, so we have them here in the southern part of the Needles Field Office where the Mojave Desert meets the north edge of the Sonoran. Their range extends to the east all the way to Texas. Ocotillo is in the Fouquieriaceae Family, and one of its cousins is the equally bizarre boojum (Fouquieria columnaris) of Baja California, a similar species that can grow more than 60 feet tall. If you’re looking for pictures of strange desert plants (which I recommend), this family is a good place to start.

In fact, I think I’ll leave you with even more plants to go look up. I learned about these from a book put out by the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum in Tucson (a good place to visit I’m told). There is a plant family called Didiereaceae that appears only in Madagascar. Do a search for “Didiereaceae” pictures. First, you can probably tell that they are totally wild and strange plants. Now compare the ocotillo pictures I’ve posted to some of the Didiereaceae plants, especially the genus Alluaudia (maybe do a separate search for this one). They look pretty similar right? Probably related? Well, it turns out that these two families are not closely related at all. Didiereaceae are somewhat related to cacti, and have succulent leaves that are different from ocotillos. And yet they have evolved with a strikingly similar appearance and growth habit. This is called convergent evolution, a process by which organisms that are not closely related are shaped by similar environmental conditions so that they evolve to have similar traits that have developed independently of one another.

How amazing is that!? Guys, plants are so cool.

Until Next Time,

-Steve

Needles Field Office, BLM