Hello, world!

Continuing from the last post, let’s look at Prosopis glandulosa shrubland and some associated plant communities from the ground and from the air. Once you’ve seen enough of it in both contexts, you can start interpreting soil types and associated species from aerial imagery. This has important land management implications. In the Las Cruces District, we have a rare plant (Pediomelum pentaphyllum) that occurs primarily in a subset of Prosopis glandulosa shrubland (a subset which is, luckily, identifiable from the air!). Also, the diversity of associated species and abundance of perennial grasses–both important indicators of the likelihood of success in herbicide treatments intended to restore grassland after grazing has led to an increase in shrubs and loss of grass–can also be predicted from aerial imagery. Double-checking in the field is still critical. However, you can’t be everywhere so, ideally, you check on the ground as much as you can, take photos and notes, and correlate that with aerial imagery to extrapolate to the rest.

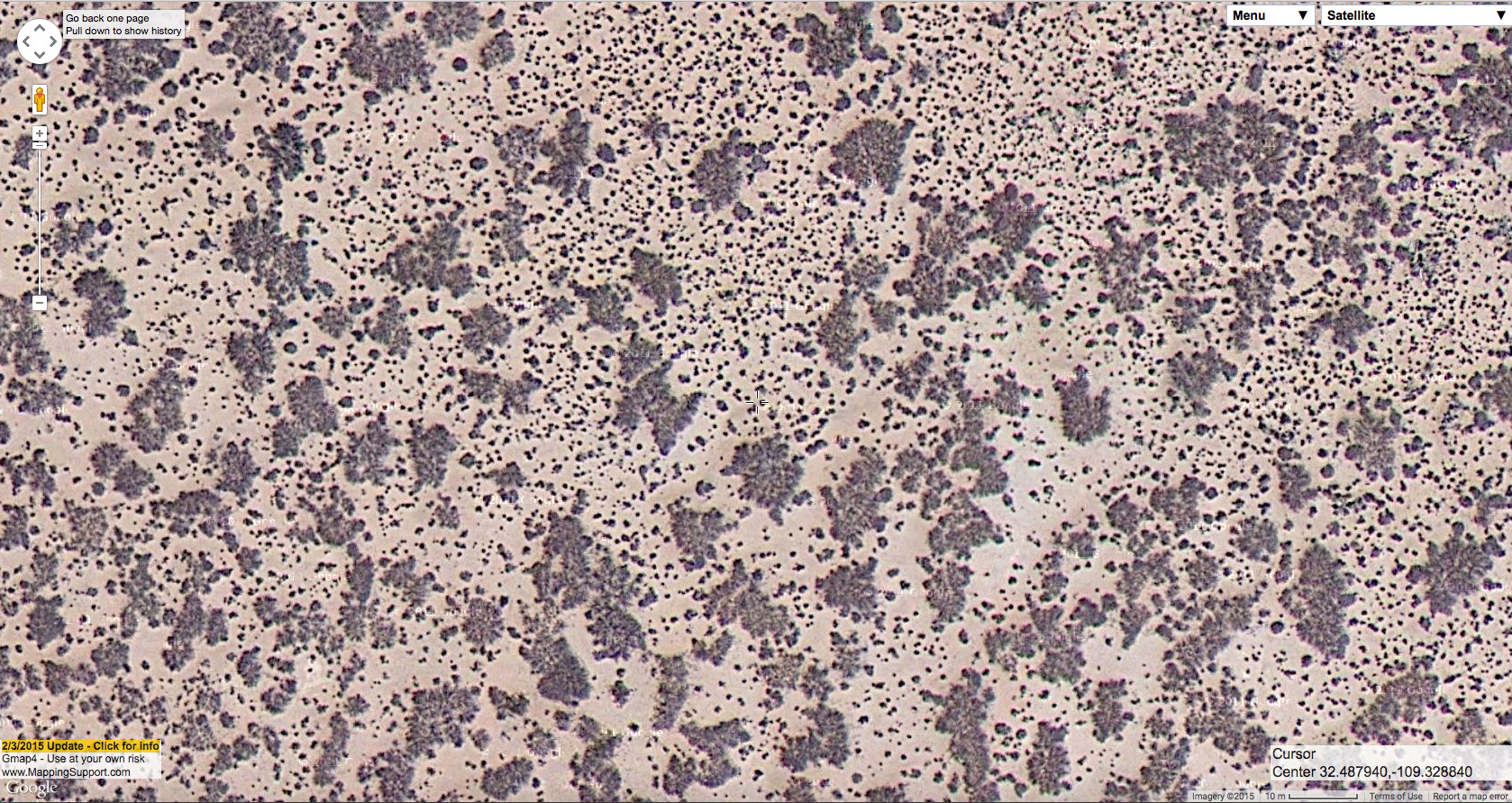

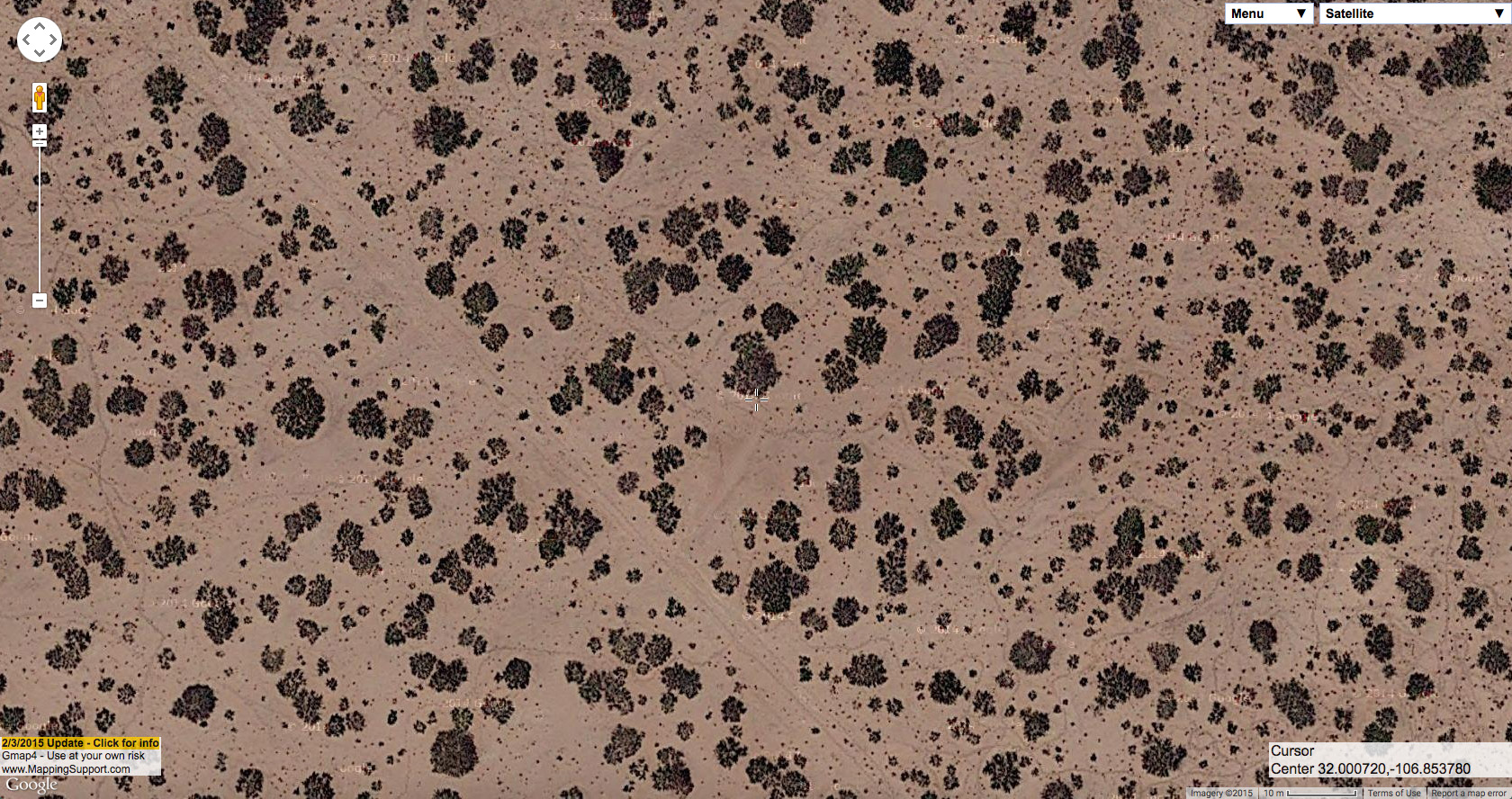

So, here’s what Prosopis glandulosa shrubland looks like in its purest form–which usually occurs with little associated plant diversity, very low abundance of perennial grasses, and a relatively firm clay-loam (or loamy clay, or perhaps just clay; I’m not a dirtologist) surface soil.

On the ground:

Same site from the air:

And another example (which you may recognize from my last post), on the ground:

Same site from the air:

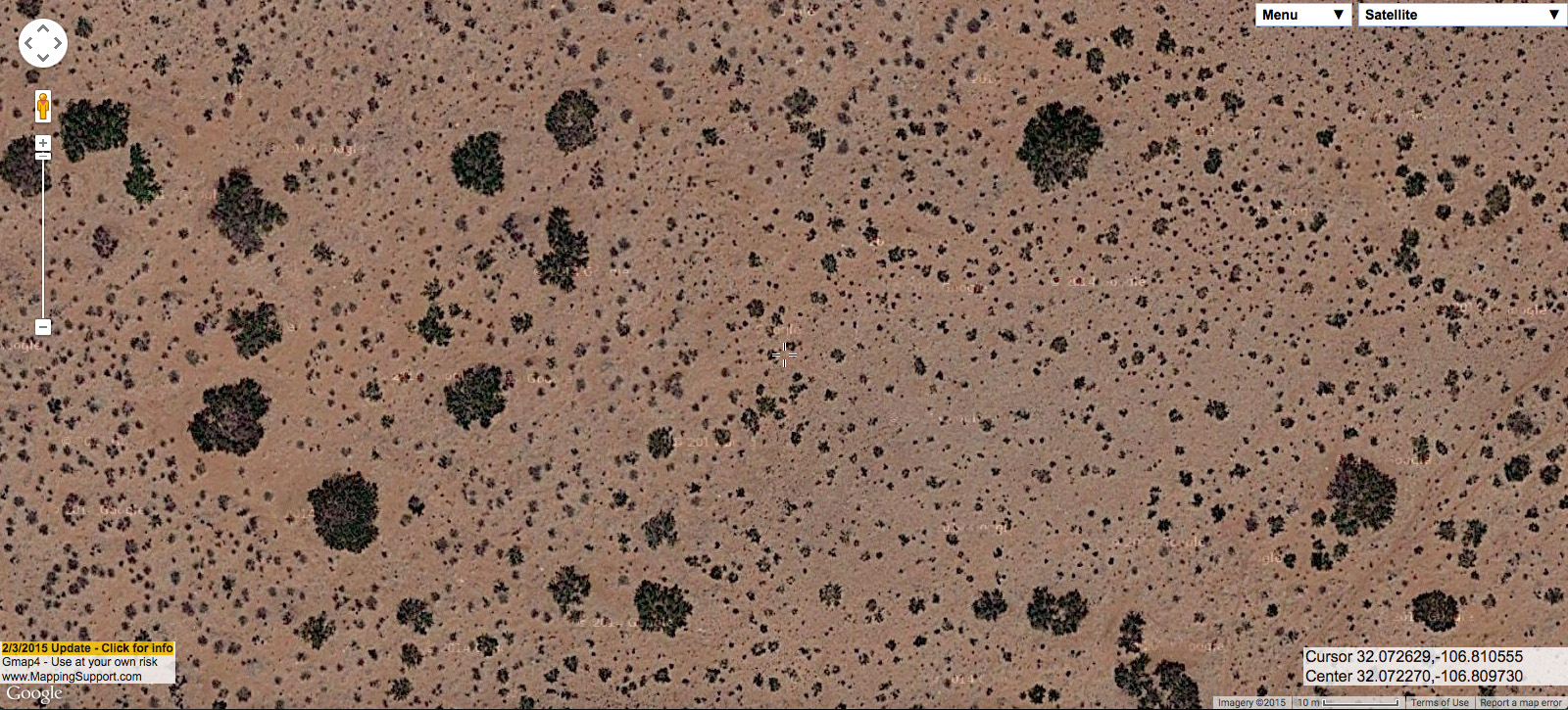

One thing you may notice from both of those photographs is that there is obvious evidence of rills caused by water erosion. This is a good indicator that there is little or no surface sand. In the second example, the exposed petrocalcic horizon along the small road is more evidence of this. The lack of surface sand is a good indication that there is probably little plant diversity at these sites and, especially, few perennial grasses. Sometimes–although not as often–very low-diversity Prosopis glandulosa shrubland occurs at sites that do have surface sand, as seen in the following example. The loose surface sand is very obvious in the field, but also identifiable in aerial imagery by the lack of any rills or gullies caused by water erosion.

On the ground:

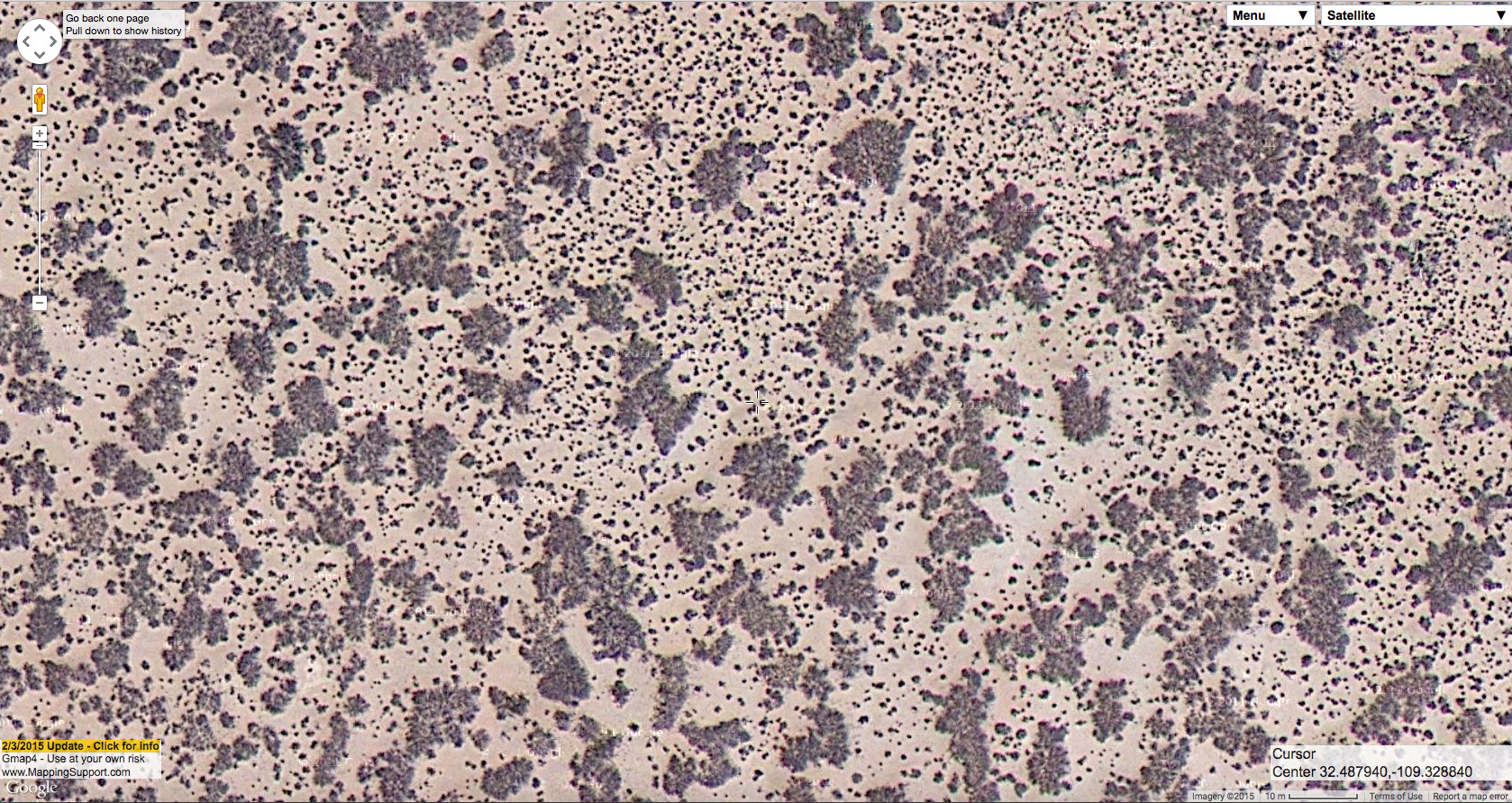

Same site from the air:

In the first and third examples shown so far, we are looking at Prosopis glandulosa coppice dunes. In this plant community, each Prosopis glandulosa has raised soil around it. It is not clear (to me, at least) to what extent the raised soil of each coppice dune is the result of deposition (soil deposited around each shrub, mostly or entirely by soil particles in wind) and to what extent it is the result of erosion (from both wind and water) in the spaces between the dunes. I suspect that, in most cases, we have a little of each. Most Prosopis glandulosa shrublands in the Las Cruces District have at least some coppice dune tendencies, but you will find Prosopis glandulosa shrubland on fairly level ground without any notable accumulation of soil around the shrub bases. The second example above is intermediate between these two extremes. The following is at the duneless extreme.

On the ground:

Same site from the air:

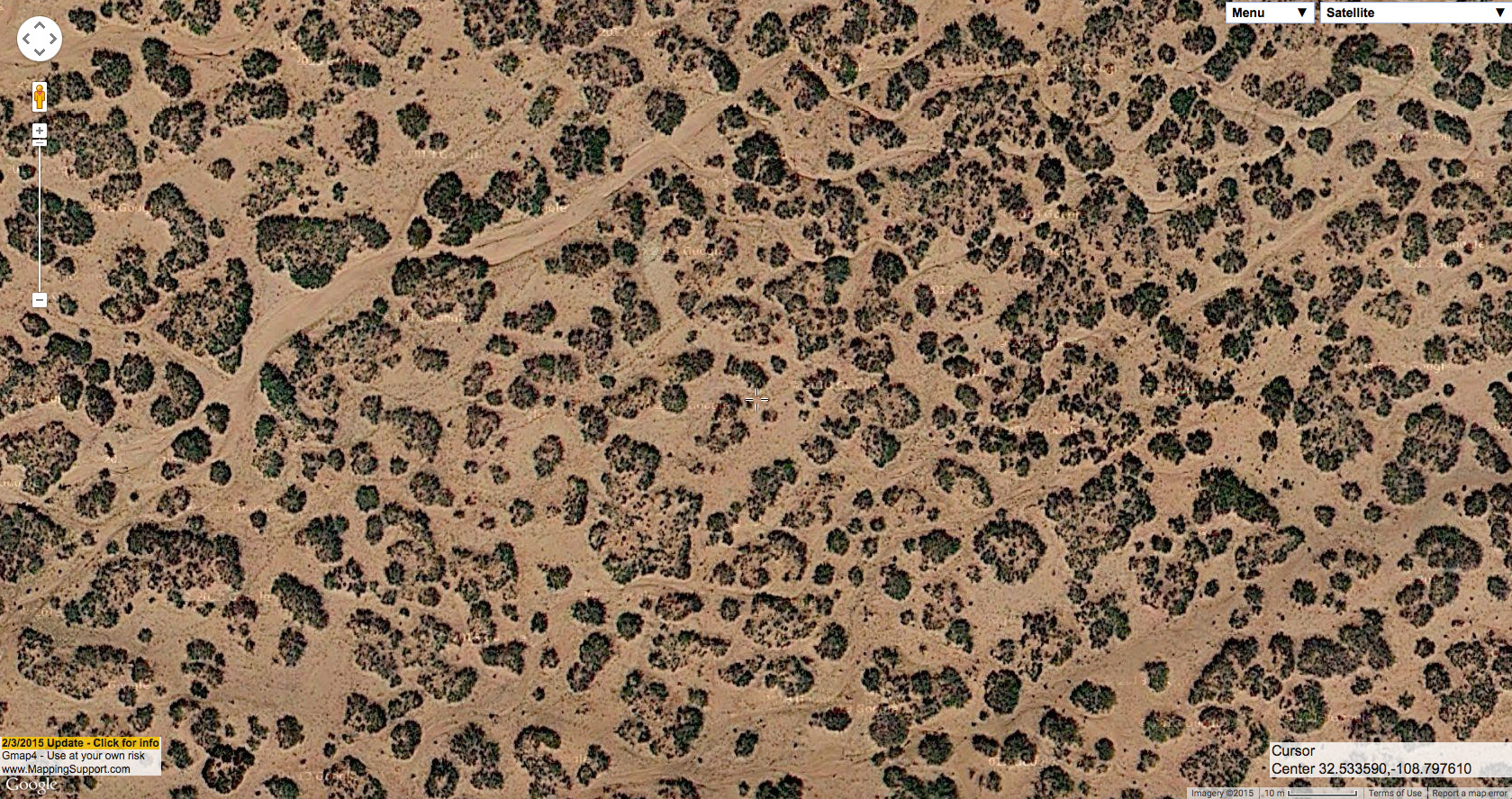

That form of Prosopis glandulosa shrubland tends to have higher associated plant diversity and more perennial grasses than coppice dunes that lack surface sand, as seen by the big, healthy Muhlenbergia porteri at that site. Prosopis glandulosa also tends to be smaller and more upright in this context. Of course, Prosopis glandulosa shrubland does not always occur in a fairly pure form. Often there are other shrubs or perennial grasses in the interspaces. At the following site, Gutierrezia sarothrae is fairly abundant in the spaces between Prosopis glandulosa, and is visible in the aerial imagery as much smaller dark blobs.

On the ground:

Same site from the air:

Usually, smaller blobs mixed in with the big, obvious Prosopis glandulosa are a good indication that you’re dealing with something more interesting and diverse than just Prosopis glandulosa shrubland. This is not always the case, as in the following example.

On the ground:

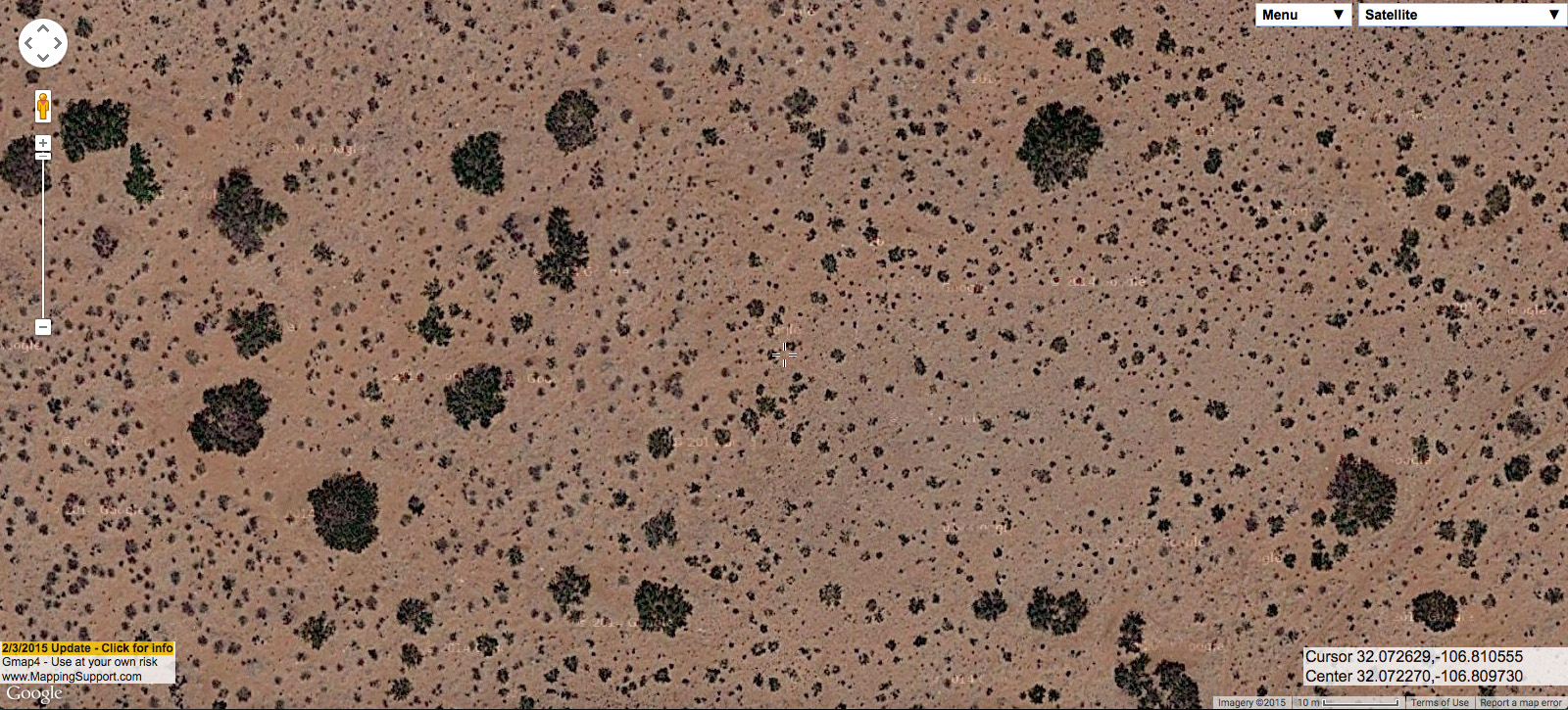

Same site from the air:

A few of the smaller blobs in the aerial image are Atriplex canescens or Gutierrezia sarothrae, but most are Prosopis glandulosa–just younger and smaller individuals. So instead of plant community diversity, they indicate demographic diversity in a single dominant species. More often, smaller blobs are other species. So, here’s an example of mixed Prosopis glandulosa and Larrea tridentata, with a few sprinkles of Gutierrezia sarothrae.

On the ground:

Same site from the air:

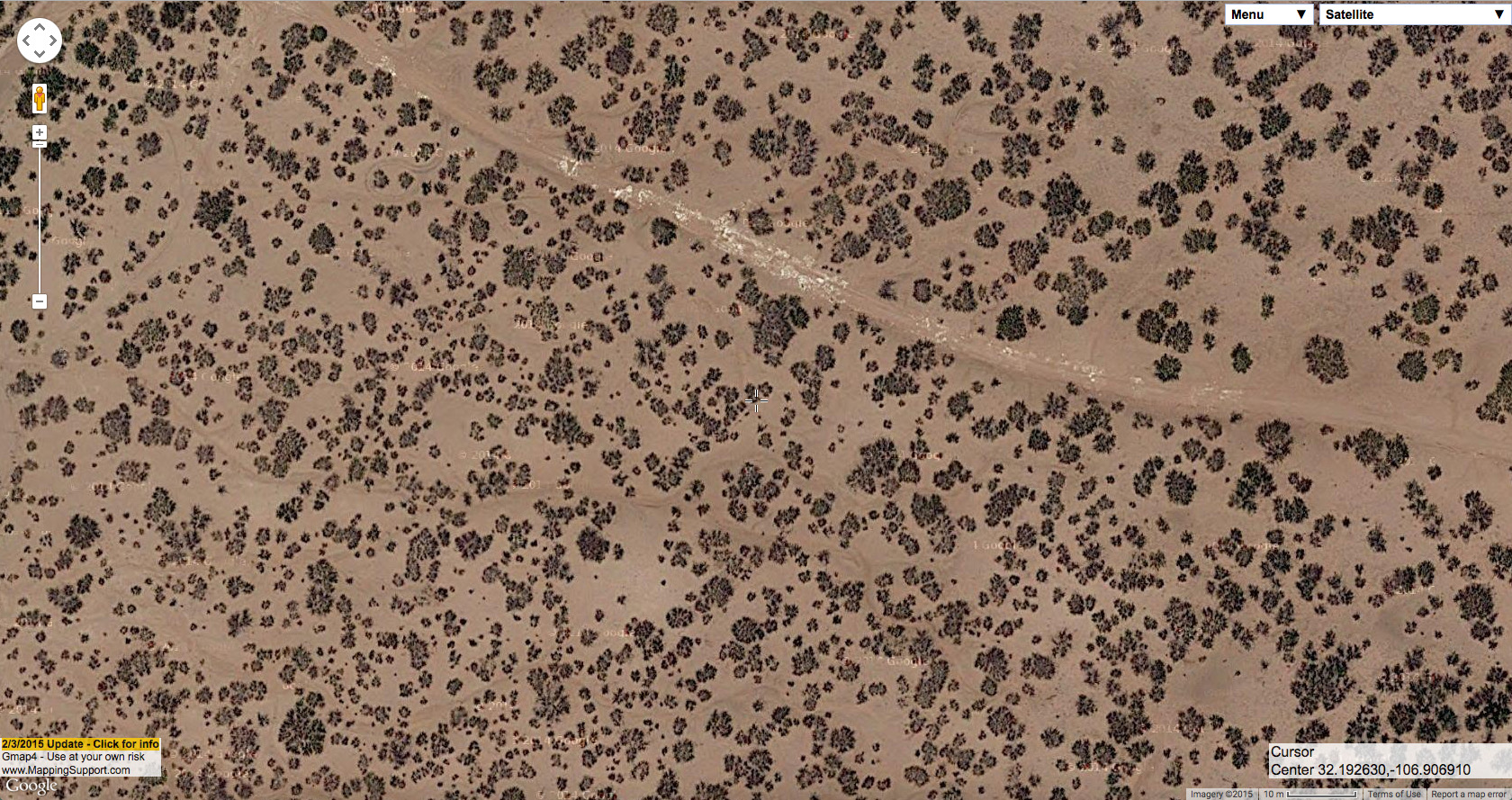

Prosopis glandulosa is also often found with Pleuraphis mutica, usually in fine-textured soils without any surface sand, as in the following.

On the ground:

Same site from the air:

Or, one might find Prosopis glandulosa mixed with Pleuraphis mutica and Gutierrezia sarothrae, as follows.

On the ground:

Same site from the air:

In cases like the two above, I would assume that we are looking at places that were formerly Pleuraphis mutica grassland with few or not Prosopis glandulosa. In the Las Cruces District, Gutierrezia sarothrae and Gutierrezia microcephala are probably the most reliable indicators of recent grazing pressure. However, although they can expand dramatically after relatively high grazing pressure, these Gutierrezia species are not particularly long-lived. Prosopis glandulosa, on the other hand, is usually a very long-lived indicator of grazing pressure. Pleuraphis mutica rarely occurs in areas with much surface sand and is relatively easy to identify from aerial imagery, so its presence is a good indicator of fine-textured, relatively sandless soil. I would also guess that these sites have relatively stable soils; Prosopis glandulosa associated with Pleuraphis mutica rarely has well-developed coppice dunes and usually has relatively few of the rills and gullies typical of pure Prosopis glandulosa shrubland on fine-textured soils.

OK, let’s move on to Prosopis glandulosa in areas that have loose surface sand. These are usually higher-diversity sites with more perennial grass. The grass at these sites in the past was probably Bouteloua eriopoda; now it is more likely to be Sporobolus flexuosus. Below is an example of Prosopis glandulosa shrubland with relatively sparse Sporobolus flexuosus.

On the ground:

Same site from the air:

Other shrubs usually associated with Prosopis glandulosa on these sandier sites are Artemisia filifolia, Atriplex canescens, Psorothamnus scoparius, Yucca elata (not exactly a shrub, but we don’t have another good word for it) and, less often, Lycium pallidum or Sapindus saponaria. Below is an example of Prosopis glandulosa with both Atriplex canescens and Sporobolus flexuosus.

On the ground:

Same site from the air:

And the following is Prosopis glandulosa with Psorothamnus scoparius. Most of the smaller blobs in the aerial imagery are Psorothamnus scoparius, but a few are just younger, smaller Prosopis glandulosa. The two have very similar morphology as seen in aerial imagery, with Psorothamnus scoparius looking an awful lot like typical Prosopis glandulosa coppice dunes, but much smaller.

On the ground:

Same site from the air:

Occasionally, you can also find almost Psorothamnus scoparius shrubland with few or no Prosopis glandulosa, as seen in the following example.

On the ground:

Same site from the air:

At the high-shrub-diversity end, you might see Prosopis glandulosa, Artemisia filifolia, Atriplex canescens, and Yucca elata all at the same site, as follows.</p.

On the ground:

Same site from the air:

Occasionally, you will even see Prosopis glandulosa mixed with Bouteloua eriopoda grassland–the plant community it has probably replaced at most of these sandy sites.

On the ground:

Same site from the air:

Once you get the hang of some of this, I think you can often get a pretty good guess of the composition, surface soil characteristics, and history of a site with Prosopis glandulosa from aerial imagery. However, everything related to the landscape (and especially, in my opinion, the New Mexico landscape) is incredibly complicated. There are exceptions to everything and thousands of rabbit-holes to go down, both literally and figuratively, in understanding the land. Ideally, this post would go on for at least another 50 pages… but I think neither I nor any readers have the patience for that.