I pressed down hard on the gas and held my breath. The truck strained as it inched forward centimeter by centimeter. Then, with a lurch, it fell back. The wheels spun rapidly, kicking up an impressive cascade of mud which rained down on the windshield in great, heavy globs. I sat back with a sigh. We were stuck.

Over the course of the summer, my co-intern Tessa and I have driven down all sorts of roads, winding dirt roads that lead to nowhere, broad gravel roads driven by thundering logging trucks, and roads covered in dense grass that bear only the faintest indication that they are roads at all.

On this day, the dirt road we were crossing was full of puddles. They started off small, nothing our trusty truck couldn’t handle. Soon though, the puddles got larger and we found ourselves taking great care to avoid the deepest spots. We got more confident as we switched into four wheel drive, but when we reached the top of a tall hill where the path below looked more like a pool of muddy water than a road, we knew it was time to seriously consider turning back. Still, we had made it this far, and we had only a bit further to go before getting back to pavement.

We drove down the hill. Slowly, as if we would anger the puddle by driving too fast, we inched our way across the mud. Then, “Squelch!” The truck stopped.

—

Last week, Tessa and I set out with our mentor, Ian, for Turtle Day 2.0. We would once again be improving habitat for native wood turtles. We were not alone though. Two trucks followed us as we headed north. One contained the Monitoring Crew and another the Great Lakes Climate Corps (GLCC). Though we had been introduced to Ottawa National Forest’s other teams of seasonal workers before, we’d rarely gotten a chance to work with them. Turtle day 2.0, however, required all hands on deck.

With shovels and mattocks on our shoulders and pruners and saws in our pockets, we hiked through the woods to reach remote riverside beaches. These beaches are known to be the favorite nesting spots of endangered wood turtles. Many of the beaches, though, have become overgrown with dense brush which makes it hard for the turtles to find ideal places to bury their eggs. This leaves the eggs vulnerable to being dug up by predators.

Our job for the day was Extreme Makeover: Turtle Beach Edition. With suggestions from herpetologists in hand, we went about digging up willow, spraying tansy, and pulling mullen, until the beaches were once again full of sandy spots that any turtle would be proud to call home. The work was strenuous, but with so many hands, the day passed quickly. At lunch time, it rained, and we sheltered in the trees swapping stories of a summer of adventures.

—

After realizing we were stuck, there were a few things Tessa and I tried. We put the truck in reverse and attempted to back out of the mud-filled pool. Earth-brown frogs hopped to and fro as the tires settled further and refused to budge.

Next, Tessa suggested that we could lay a path of sticks in front of the truck to give it some much needed traction. I thought this was a brilliant idea. Stepping out of the truck, I quickly realized that the opaque surface of the puddle hid a rut that was less on the scale of a few inches deep and more on the scale of a few feet deep. In places, the water came up to my knees. We gathered great arm-fulls of sticks, but when we tried to set them in place, they floated away.

On a feeble hope, we put the truck in neutral and tried to push it. It didn’t move. Deep down, I knew we would be fine, but as we strained to push the big white truck I couldn’t help but feel cold sweat on my palms and a tightness in my chest. The forest suddenly felt very big and I felt very small.

After another few minutes racking our brains, we realized it was time to accept it, we would need to call for help.

First, we glanced at our cell phones. No service. Next, we turned to the radio, but all of the channels looked unfamiliar. Thankfully, we had a SPOT device with us, which can send a location along with limited messages from almost anywhere in the Ottawa. The best message for our situation, “We need help, but it isn’t urgent” seemed a great deal better than nothing, yet frustratingly vague. Tessa suggested we climb the nearby hill to see if there might be cell service there.

Success! A feeble bar showed up at the top of Tessa’s phone. It was enough to get a phone call out to our mentor Ian. He’d head back to the office and grab supplies, he told us, and be there as soon as he could.

—

This month, Tessa and I have been tackling purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria). Purple loosestrife is, simply put, a gorgeous plant. It bears numerous showy purple blooms, which stand out strikingly against the greens of the forest. The flower loves any place where water transitions to land, be it a lake, river, or roadside ditch. Its dense roots cling to the mud while its tall stems reach for sunlight. Unfortunately, when left unchecked, this invasive flower can completely take over, crowding the coastline until there is only purple.

Tessa and I have been tasked with following the plant wherever it grows (within the forest), mapping it along highways as cars rush by, wading along lake shores to cut the tall, square stems, and paddling down rivers to pull the plant up by the roots.

That was our objective early on a Friday morning, as Tessa and I loaded the canoe onto the truck, or, I should say, attempted to load the canoe on to the truck. The back of the boat extended a good seven feet past the end of the truck bed. We sent a photo to Ian who agreed we should head out without the canoe. He would reach out to the partner organizations we would be working with that morning to see if it would be possible to find some alternative floatation.

We were the first ones to arrive at the boat launch. We got into our waders and ate wild raspberries while we waited for more people to arrive. After a few minutes a car pulled up, loaded with canoes and kayaks. We introduced ourselves and were greeted warmly. Before we knew it, they were showing us how to identify a reed grass called phragmites which is often invasive. They pointed out the length of the little tuft that most grasses have where the leaf meets the blade and the color and texture of the stem. These were all indicators, they explained, that could help distinguish the native phragmites from the invasive. No doubt about it, we had found our people.

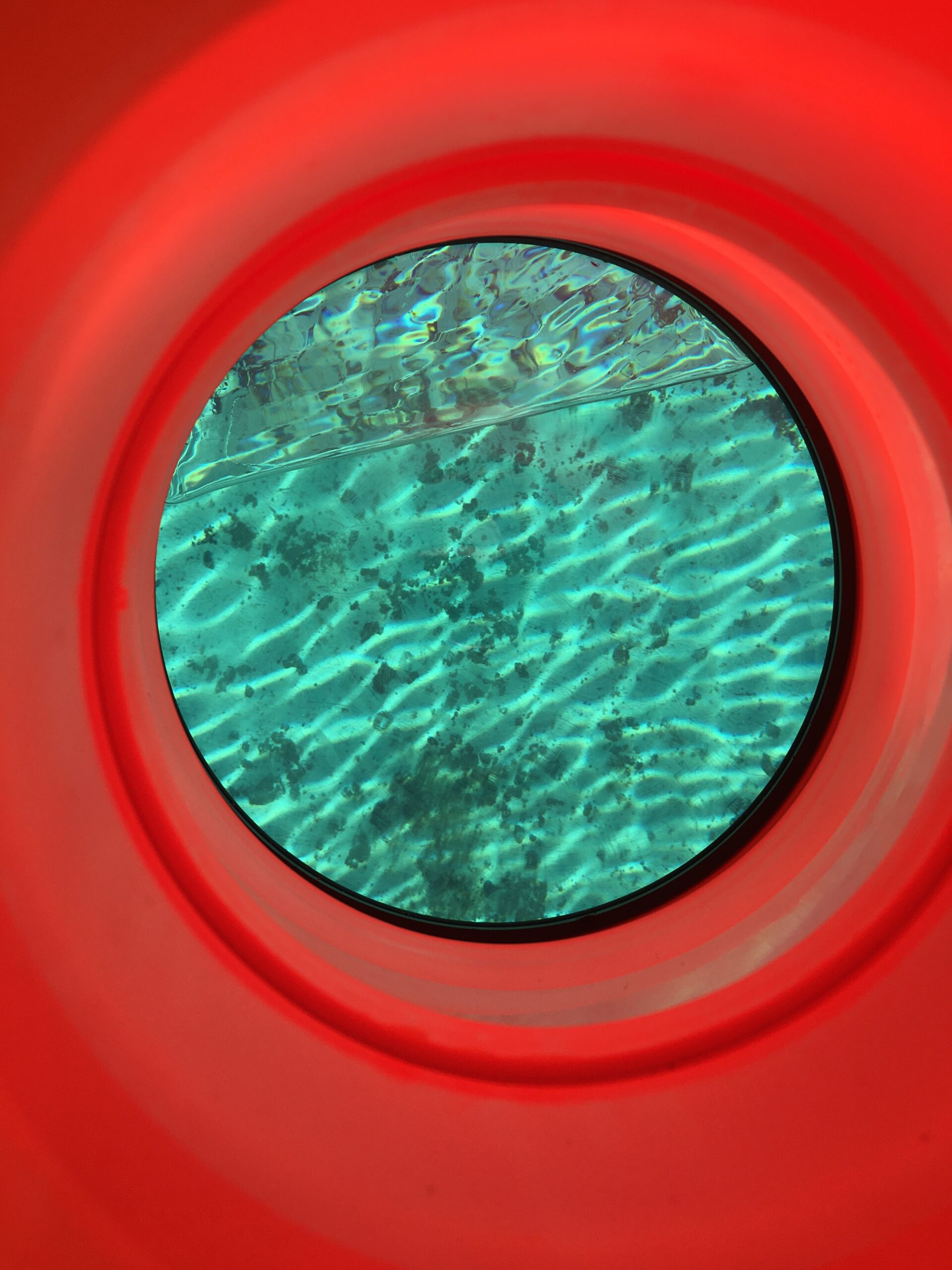

A few minutes later and more partner organizations had arrived. Some were familiar faces we had worked with before and some were new. When all was said and done, we had a crew of nine people. Upon hearing about our canoe conundrum, they had brought extra kayaks for Tessa and I. Loaded with dry bags, sunscreen, and shovels, we were ready to hit the water.

We spent the day paddling our way along a river, pulling the purple loosestrife that had made a home there. The loosestrife in this area had never been treated before, so pulling up each loosestrife proved a wrestling match. Still, with so many people, the work passed quickly. At the end of the day, we left with half a dozen garbage bags full of loosestrife, a sense of deep satisfaction, and some new friends.

—

With Ian on his way, there was nothing to do but wait. I sat on the truck bed and watched the frogs dive beneath the water. Tessa sat with me and we talked about small things. She read me a letter from a friend back home, and I read her a few poems from a book I carry in my backpack. Sitting there with someone else, the knot in my chest seemed to unwind just a little.

Slowly, the time passed. We ate lunch, and then, decided to climb the hill again to see if Ian had sent any messages. As we crested the hill, we could just see a Forest Service vehicle carefully making its way across the puddles. Ian had arrived!

In the minutes that followed, Ian reviewed best practices to avoid getting stuck and taught us how to use a winch. The device is essentially a giant lever attached to a reel of cable. One end of the winch is attached to a stuck vehicle and the other a suitable sturdy tree. As the lever is pumped, the cable gets shorter. In the end, either the car moves or the tree does.

—

On a bright, sunny day, Tessa and I drove to Wisconsin. We were headed to an invasive plant management workshop hosted by a local university, a weed management cooperative, and an assortment of pesticide businesses. Arriving at the address, we found ourselves next to lake Superior. We filled out name tags and grabbed muffins from the refreshment table as dozens of people who had the distinct look of folks who spend a lot of time outdoors filled in.

One by one, the attendees introduced themselves. People had come from all sectors to attend the conference. Some were local government workers, some were federal government workers, some came from nonprofits, and some came simply because they wanted to learn more about weed management. There were seasoned veterans and interns like us, all chatting, comparing notes, and catching up.

To start the day, we all piled into a school bus. After a bumpy ride, we arrived at a stretch of out-of-the-way roadside. The conference’s experts took us through the different weed treatments that had been applied to various sections of the road. They were happy to answer questions on everything from the right time of year to apply pesticides to how to target weeds effectively while leaving native plants minimally disturbed.

After heading back to the conference venue, we watched a presentation on local invasive species identification and management. Then a scientist and weed management expert answered questions from the audience. Sitting in the crowd gave me a chance to appreciate the deep symbiosis between research and management. He shared the latest findings on effective weed control with the room and listened with interest to the questions and observations of the weed managers. At the end of the conference, all of the experts invited the attendees to reach out to them with questions big or small.

Some of my favorite moments of the conference were the unstructured times, those moments in between the lectures and presentations when the attendees and experts got to chat informally, ask questions, swap stories, and build relationships. Listening to the conversation, it was clear that everyone at the conference was united by some common goals: control the spread of harmful invasive species, limit their damage to the manmade and natural world, and educate the public about the invasive species in their area so that management work can been done in collaboration with the community.

Most days, Tessa and I are alone. We can spend all day in the forest without ever seeing another person. Attending the conference reminded me of the larger network of people that are working all over to continuously ask new questions, tackle new projects, and promote conservation and stewardship in cooperation.

This is essential because managing invasive species is a massive task. A map of invasive plant sites in Ottawa National Forest quickly begins to look like a map of stars in the sky, with thousands of infestations scattered all over. Thankfully, though we’re not managing these sites alone. Other forest employees, numerous partner organizations and volunteers, and every person who washes their boat between lakes or wipes off their shoes after a hike is managing invasive species right alongside us.

From Turtle Day to our loosestrife paddle, all the biggest projects we took on this month we took on with other people. We’ve had the opportunity to learn from so many wonderful land managers who are generous with their time and insights. In so many ways, this summer has been a continual process of offering help to others and finding in turn that, when we need it, help is never far away.

—

Bit by bit, the truck began to move. Still, as Tessa pressed the gas, the tires spun. Finally, with a great heave, the tires began to roll. Not spin. Not splutter. Roll. We had traction. We were unstuck at last.