These past few weeks, soil has been on my mind. Blowing in through my ears, landing in the crevices of my brain. I’m hoping it’ll fertilize my mind into feeling grounded, encourage some new growth. Inevitably, I’m always drawn to soil when in need of grounding. I appreciate how literal it is, to be connected to the Earth, dirt under my nails, nibbling on roots. And I can get lost in the wonder of it all when I consider soil, how it nourishes us, brimming with life and mystery, a hidden world under our feet, supporting us as the foundation of life.

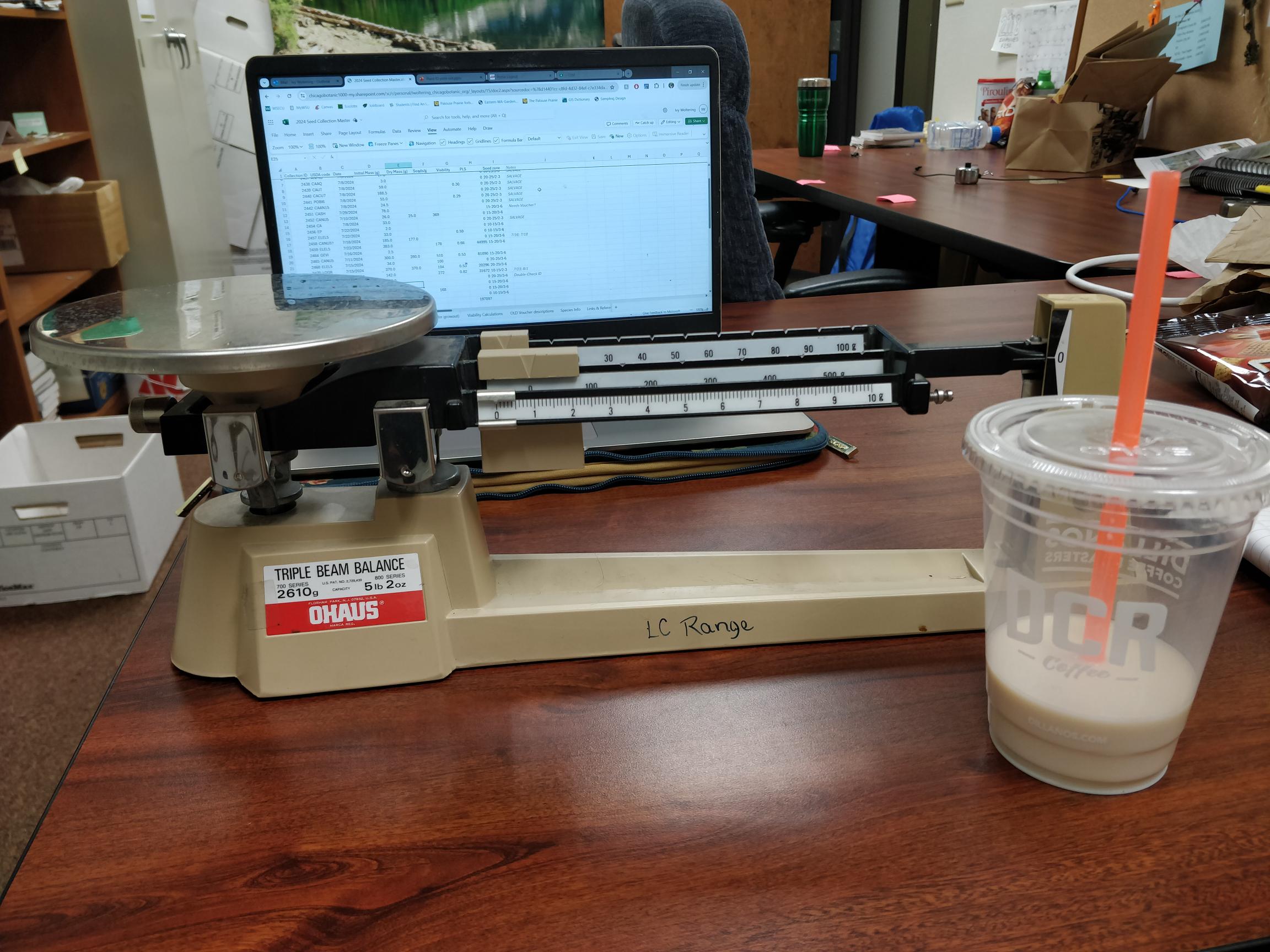

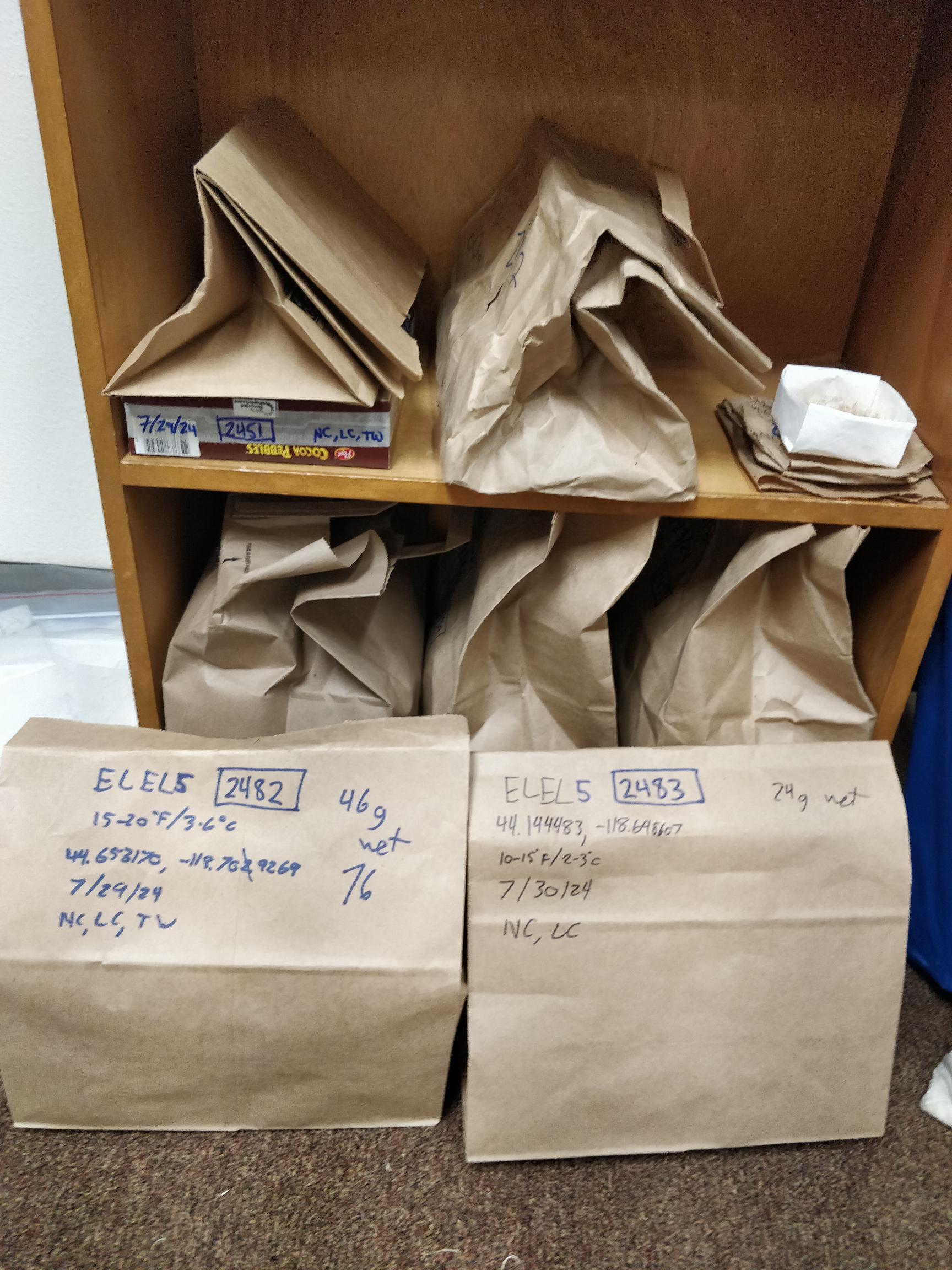

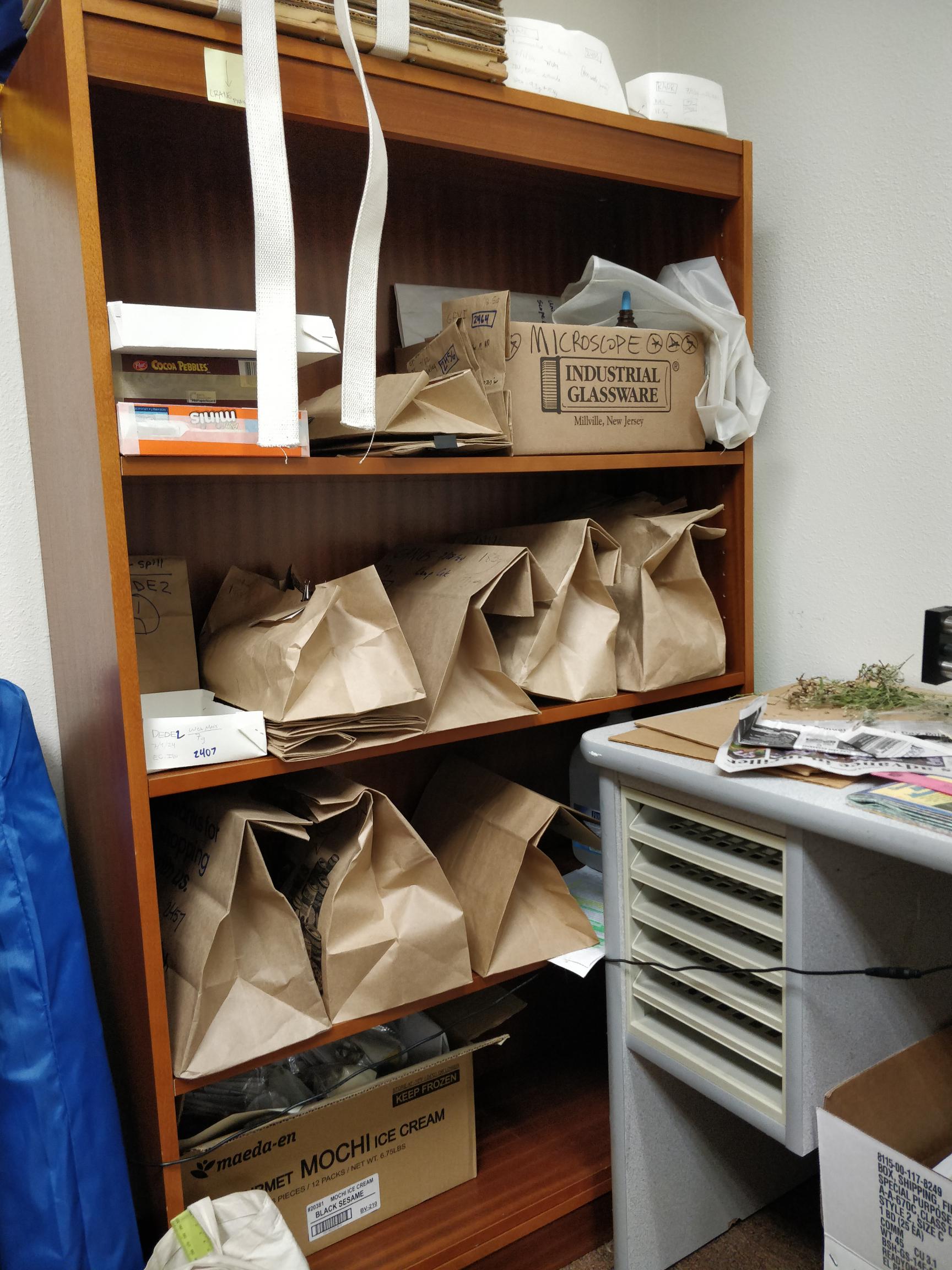

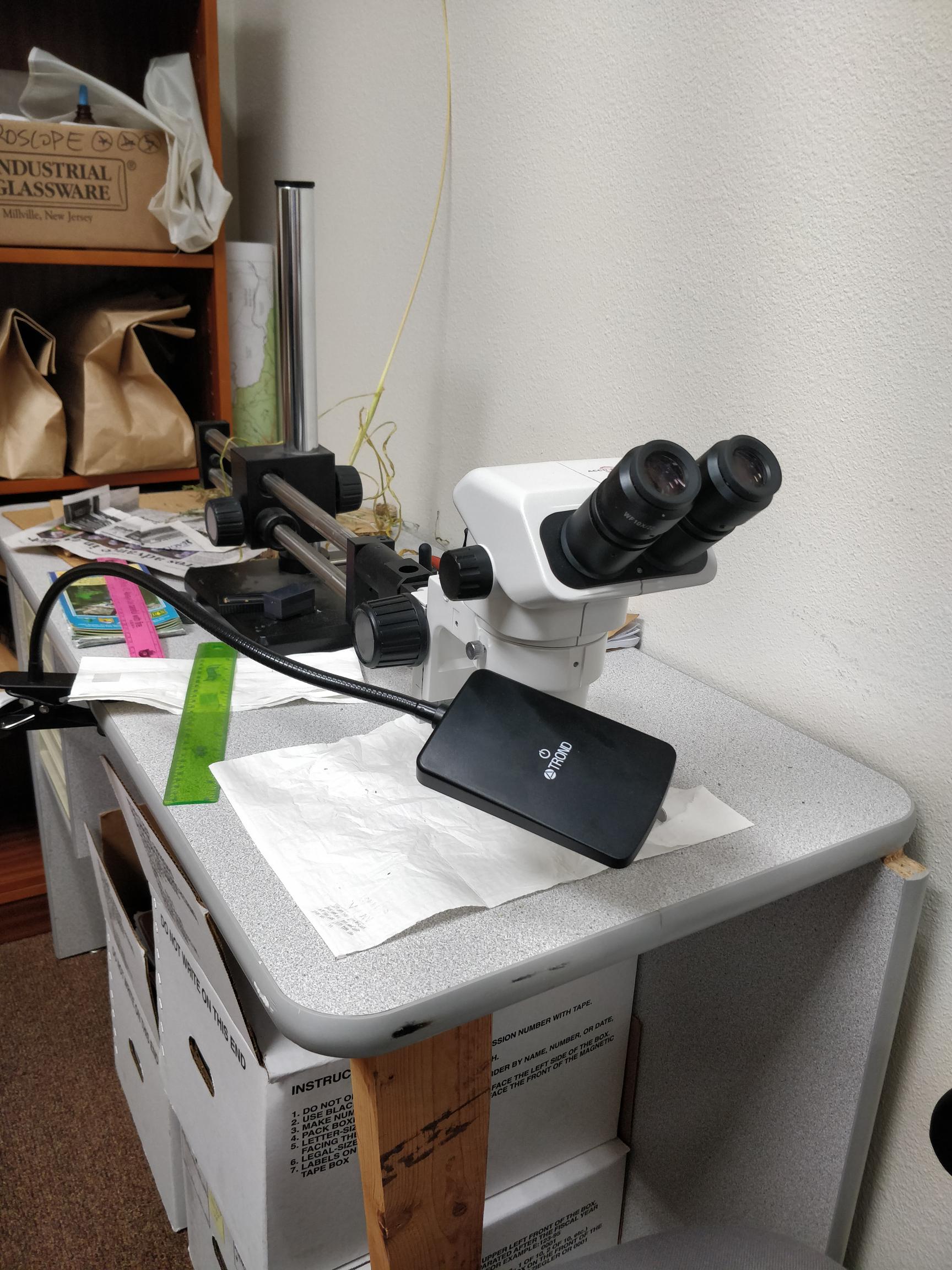

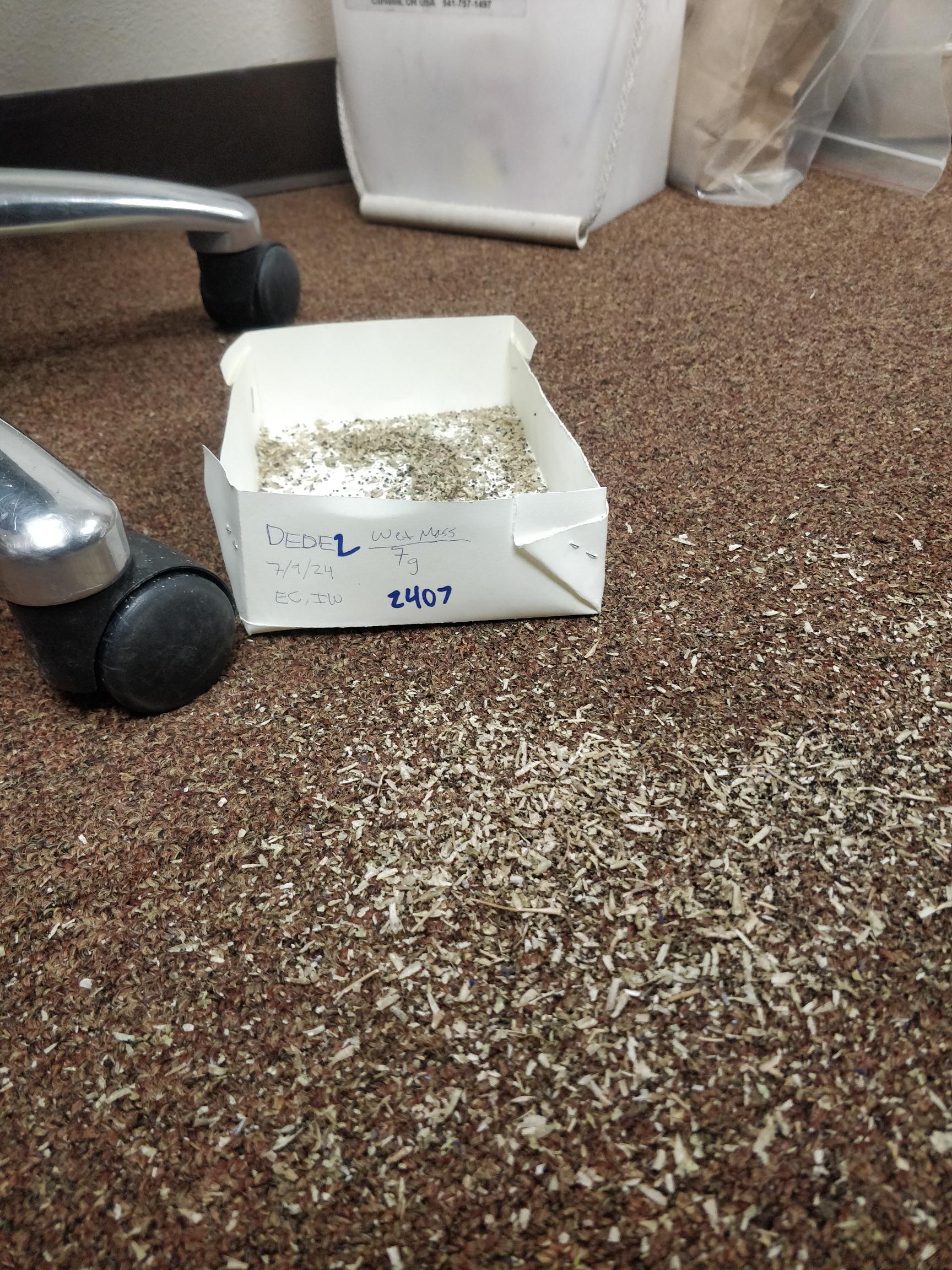

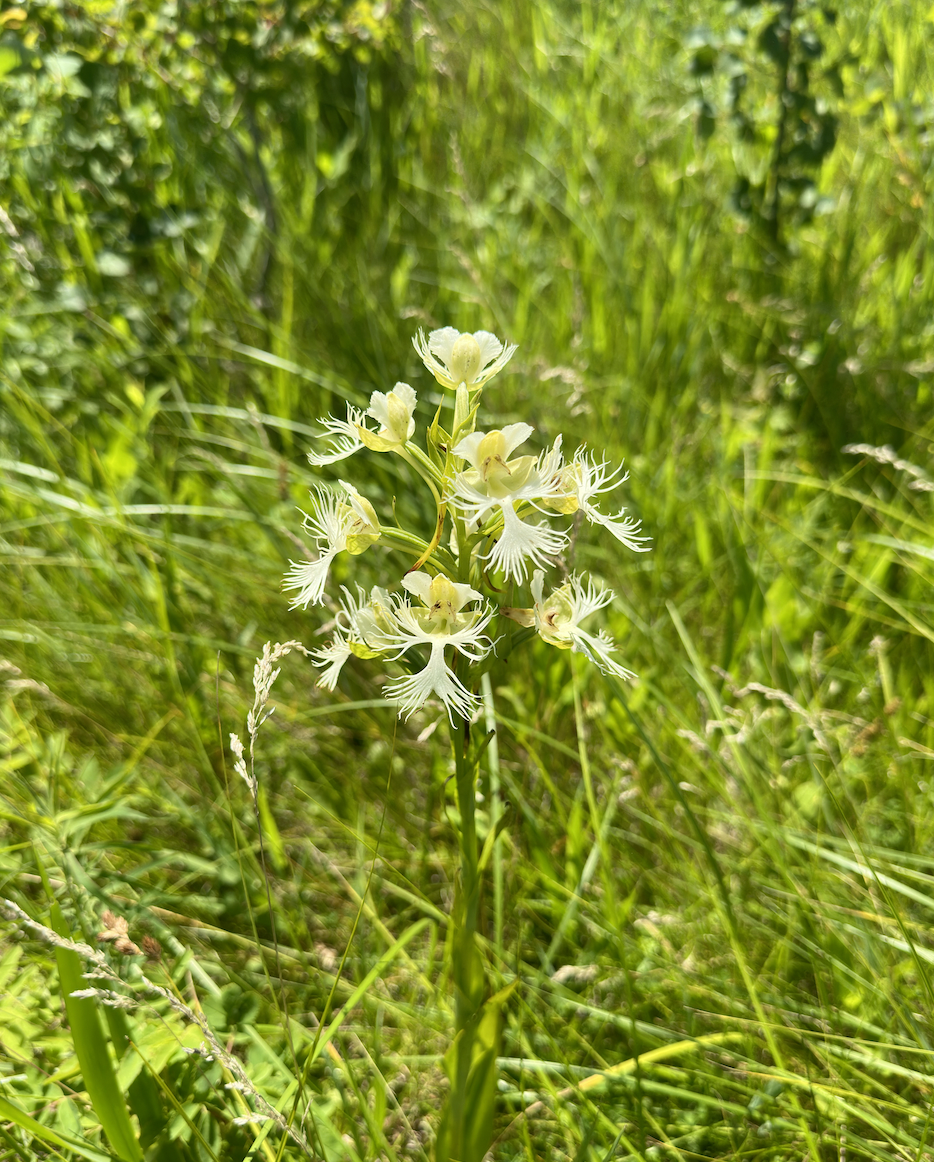

This last month, our grasslands research has included preparing bud core samples that my boss harvested for analysis. The samples start as chunks of the earth- foot high grass culms and their dense, clayey root bundles. We hold the dried root bundles under the blast of the hose, breaking off chunks of clay, combing out rhizomes and fine roots the way you’d comb out hair or wash a dog. The reveal is beautiful. There’s an immediate recognition and appreciation that finally you’re seeing the whole plant. It’s like the floor washed away and you can see all the pipes and mechanics and innerworkings of your city. Like you can finally really understand where it all comes from. Washing the soil from Pascopyrum smithii’s below ground structures reveals a story, and our boss, Jackie, translates it for us. This is her language, and she tells the story with familiarity and adoration.

“Here is last years’ culm, and here it decided to put up a new shoot! I predict that drought will have less impact on the number of buds, but more so on their development and energy invested by the plant.”

She shows us three years’ generations of grass shoots, spaced neatly along the rhizome, the newest looking young and fresh, the oldest greying and soft. From above ground, you could never translate this familial story, but understanding roots entirely changes the way I see the prairie.

The metaphors are enough for me to get lost in. When I was in undergrad, I tattooed “as above, so below around my kneecap. Soil exemplified this for me. Ecology and geology lessons left me reeling, the interconnectedness of it all…the rocks, the soil, the plants. Nourishing, growing, dying, returning. The cycles, all the cycles… inducing a mania over all the love pouring from rocks. To me, learning the ways in which soil was alive was reflected in community structure, resilience, and cooperation, and a thread of love throughout all levels of life. It taught me about foundations, being grounded, and about putting down roots.