The prairie, although not as sprawling as it once was, is an ever-changing beauty to behold to anyone who sets their eyes on it. The beauty of the prairie can easily be captured, in my opinion, through the lens of a camera. In general, I feel more people need to know what the prairie has to offer and I hope my photos can help to inspire many.

June:

In June, a majority of the plants I photographed tended to be species that preferred dryer, sandier soils like Lead Plant (Amorpha canescens), Canada Milkvetch (Astragalus canadensis), and Pale Purple Coneflower (Echinacea pallida). The Troublesome Sedge (Carex molesta) was an exception since it grew in a seasonably wet field with clay. I also felt like a sedge needed to be included in the group of photos, as sedges are more than just plants with edges!

(Amorpha canescens)

(Astragalus canadensis)

July:

The photos from July were taken from a diverse amount of locations such as the typical tallgrass prairies, dolomite prairies, and wetlands. For the typical tallgrass prairie habitats, Prairie Blazing Star (Liatris pycnostachya) and Sullivant’s Milkweed (Asclepias sullivantii) were somewhat uncommon sights, as compared to their more common relatives, Dense Blazing Star (Liatris spicata) and Common Milkweed (Asclepias syriaca). As for the dolomite prairie and the wetland habitats, Nodding Onion (Allium cernuum) and Dark-Green Bulrush (Scirpus atrovirens) were very common plants to see and photograph.

(Liatris pycnostachya)

(Allium cernuum)

August:

For August, we visited primarily typical tallgrass prairie habitats. The first two species I photographed this month were the Tall Coreopsis (Coreopsis tripteris) and Sawtooth Sunflower (Helianthus grosseserratus). Other species in this habitat included the Round-Headed Bush Clover (Lespedeza capitata) and the Great Plains Ladies’ Tresses (Spiranthes magnicamporum).

(Coreopsis tripteris)

September:

In September, there was an abundance of golds and yellows as most of the Goldenrods (Solidago sp.) were in bloom. Of the goldenrods, the Old Field Goldenrod (Solidago nemoralis) was one of the first that I noticed blooming. Nearby, Prairie Dock (Silphium terebinthinaceum) was still in full bloom with an insect that I believe to be one of the signs of fall, the Goldenrod Soldier Beetle (Chauliognathus pensylvanicus). In addition to the Goldenrods and Silphiums, the white ray flowers of White Heath Aster (Symphyotrichum ericoides) were also present. Also in bloom within the wetlands was the carnivorous Common Bladderwort (Utricularia macrorhiza).

(Solidago nemoralis)

(Silphium terebinthiaceum)

(Utricularia macrorhiza)

October:

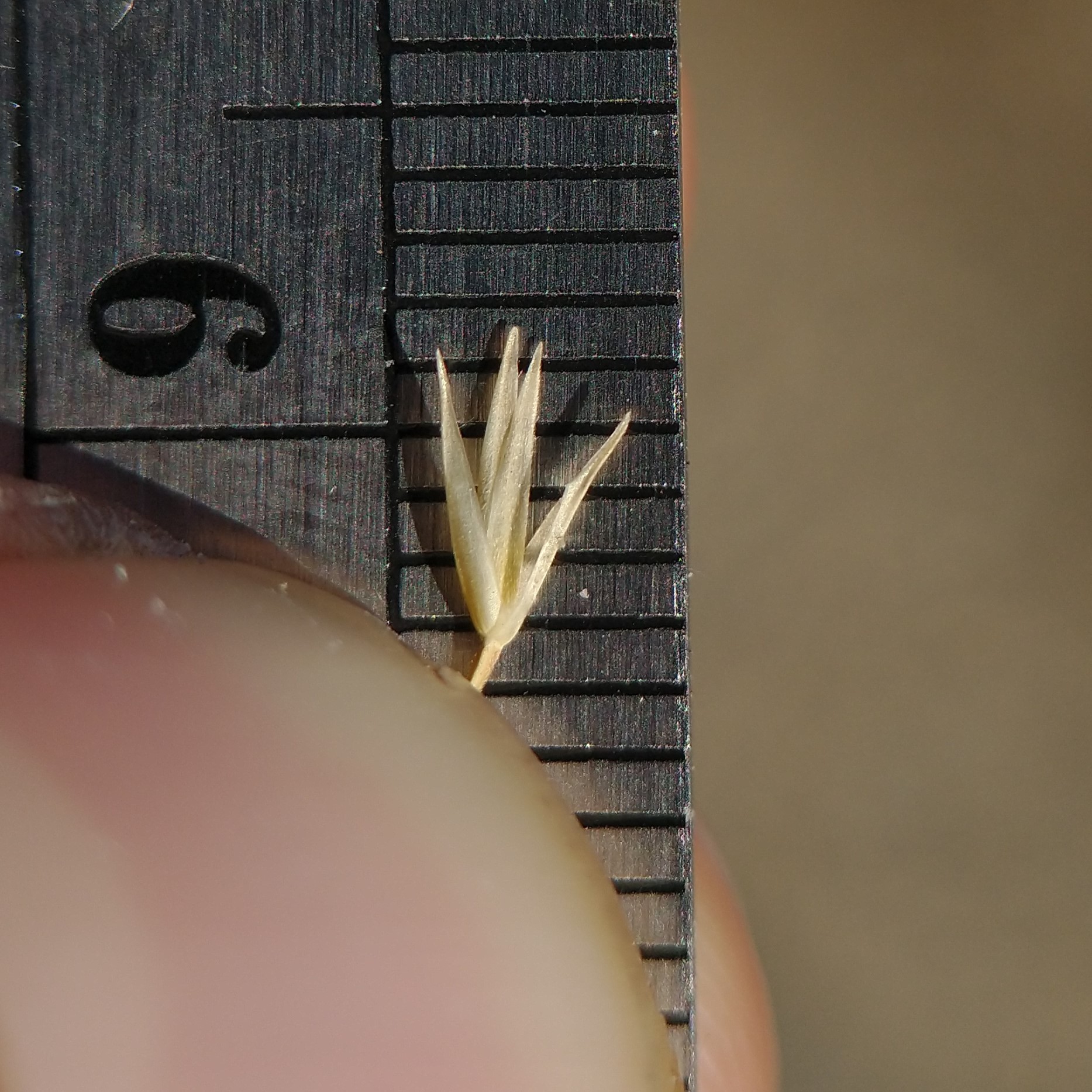

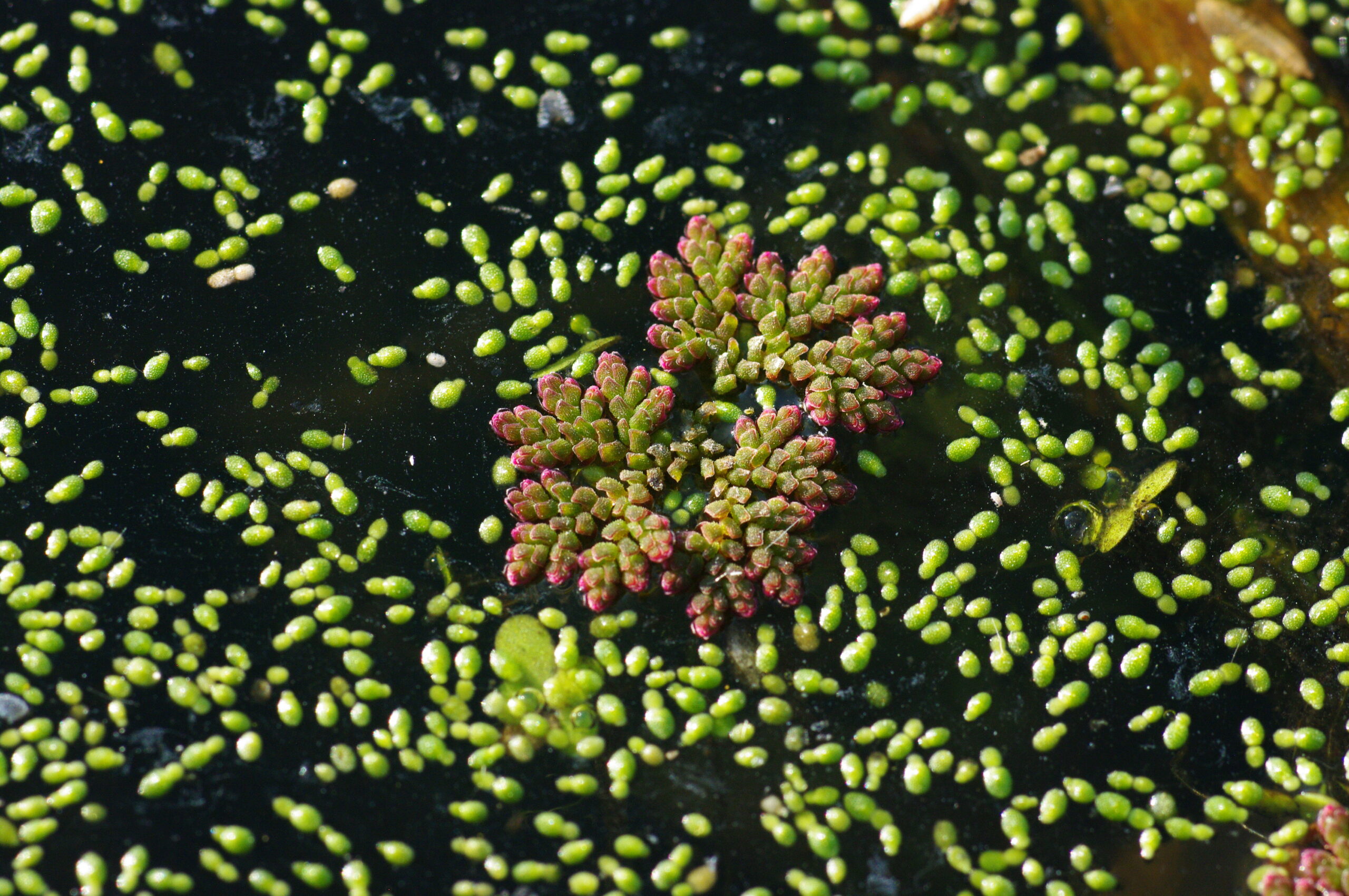

At last, October! During October, we primarily cleaned seed from the collections we made during the summer, so I did not take many photos on my camera. When we did collect seeds, we went to the wetlands and back to the dolomite prairies. In the wetlands, we came across the tiny Mosquito Fern (Azolla caroliniana), whereas in the dolomite prairie, we were greeted by the Aromatic Aster (Symphyotrichum oblongifolium).

(Azolla caroliniana)

(Symphyotrichum oblongifolium)

Although I may have missed the prairie’s beauty during the spring, I am glad I witnessed the beauty it offered throughout the summer and fall with my fellow Midewin CLM interns! The photos, although just of plants, remind me of the fun memories we made during our five months as interns. Although this is bye, for now, Midewin, I will be back to continue appreciating and photographing the prairie!