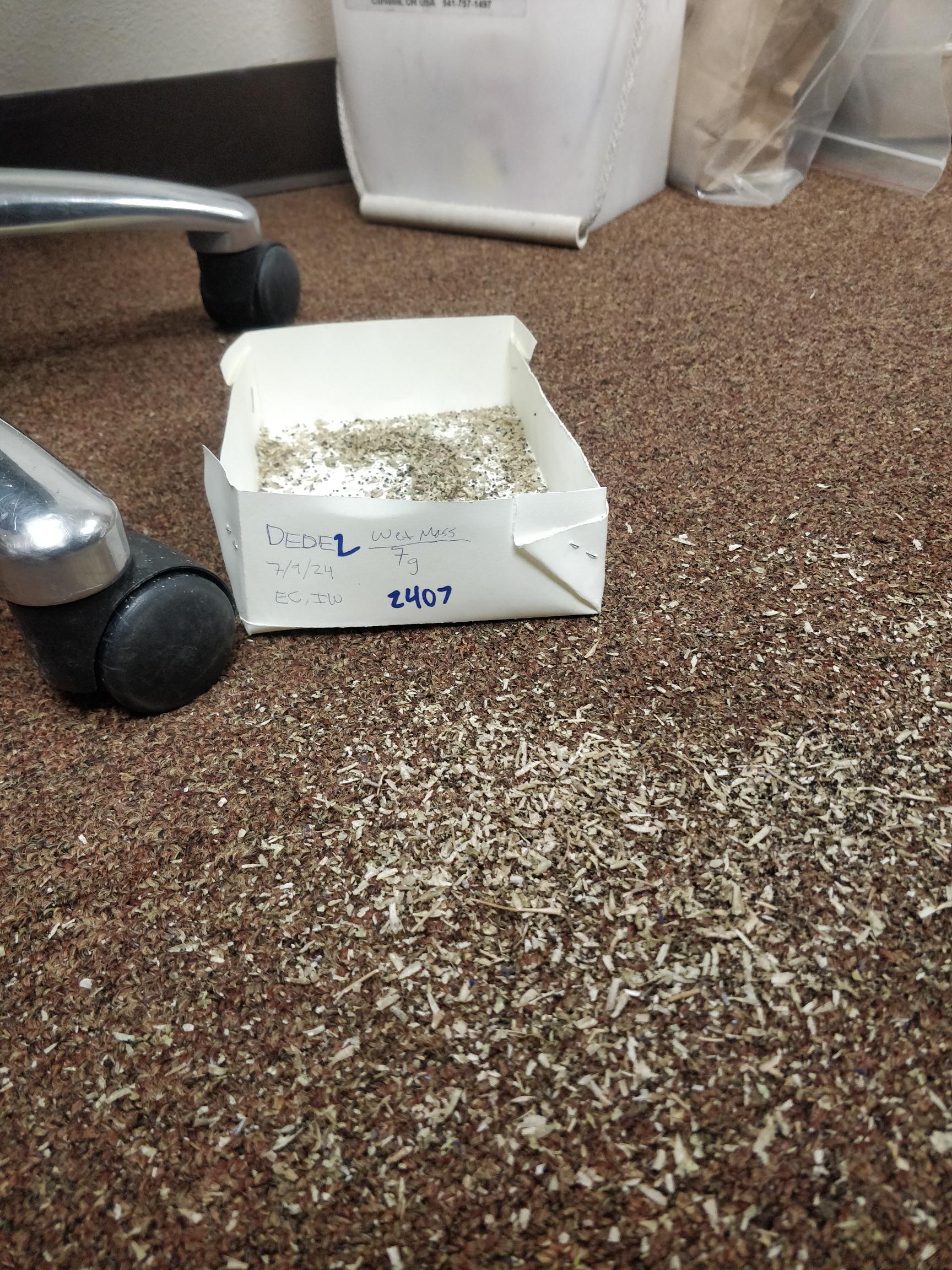

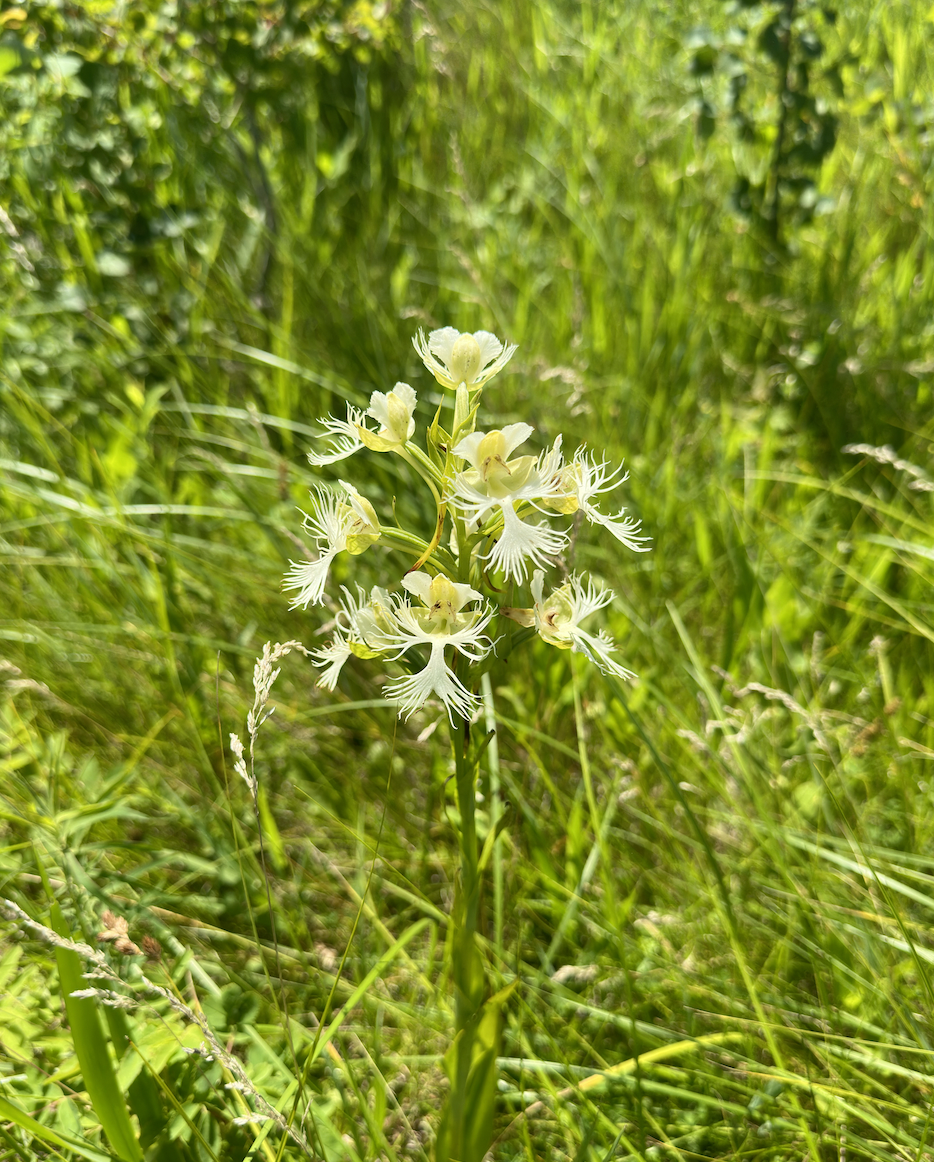

I’ve been working in the Umpqua National Forest for a month and a half now, and in that time, I’ve witnessed incredible changes in the landscape around me. I’ve made memories that I’ll cherish for a long time, and I’ve captured countless photos. Beyond the breathtaking scenery I’m fortunate to work in every day, the most fascinating transformation I’ve observed has been the plants’ progression from fruit development to seed dispersal. This shift in the natural world has also marked a change in my work, as I’ve transitioned from managing invasive species to the exciting task of seed collection. So far, we’ve gathered seeds from 14 different native species (to list a few: Oregon sunshine, yarrow, blue wild rye, red columbine, deer vetch, serviceberries, etc.)

In this short time, I’ve learned so much. Being part of a larger botany team—nine strong—composed of like-minded, hardworking individuals has been an incredible experience. Our shared enthusiasm turns each day’s work into a collective endeavor that feels both purposeful and rewarding. We’ve supported each other through challenging tasks, celebrated our successes, and learned from the forest and from each other.

However, the recent wildfires here in the Umpqua National Forest have posed a significant challenge. These fires have lead to forest closures that overlap with many populations of interest, which has forced us to adapt and develop new strategies. These have included scouting for new populations to collect from that are large enough and with viable seed, with no previous historic data. Another hardship has been waiting for waivers to come in to permit us to enter parts of the forest closed due to fire activity, which has delayed both scouting and collection efforts.

The work we do in managing invasive species and collecting seeds becomes even more crucial in this context, as these efforts help to ensure that the forest can recover and continue to thrive after a fire. In the end, my experience here has deepened my appreciation for the delicate balance of nature and the critical role we play in preserving it.