Ross Gay, in his collection of essayettes, The Book of Delights, ruminates on the nature of delight. He believes delight is a type of invitation to notice the things and events happening and unfolding around us, and find joy in their spontaneity and sorrow, their strangeness and their beauty.

Which is to say… seeds are here! Across the Tongass, plants are teeming with seeds of their own making. And we are taking some of them. Collecting seeds is a delight, which means it is about paying attention. It is also a meticulous and at times, tedious, act. For this post, I will revel in this delight: the detailed beauty of fruits, capsules and pods, and their accompanying seeds.

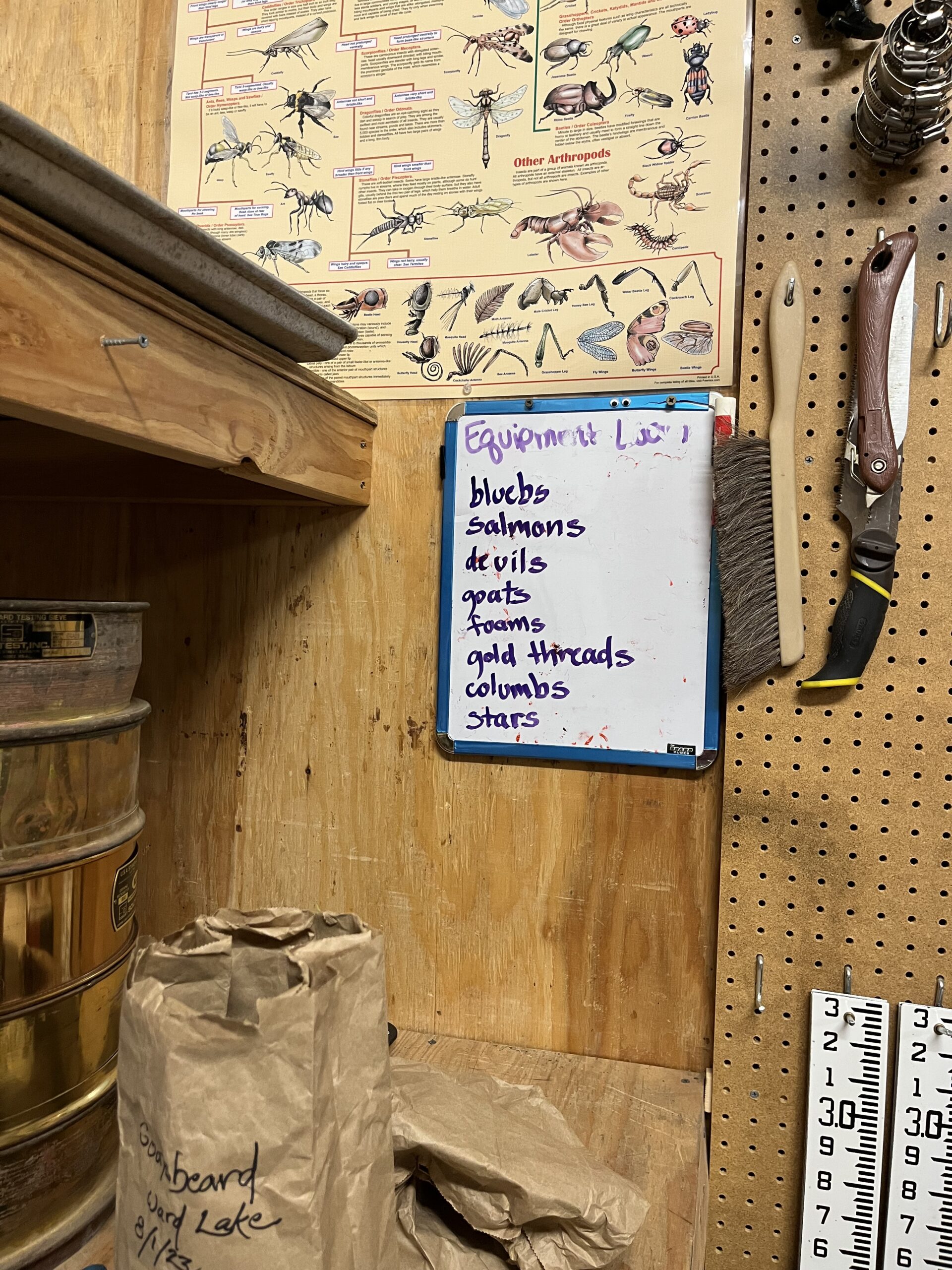

Western Columbine (Aquilegia formosa) is an elusive forb that often stands alone or in smaller groups, making it difficult to find an extensive enough population to collect from. But, early this month, we encountered a steady group of them on the side of a freeway on Prince of Wales Island. Only a few bowing red and yellow heads remained — most had hardened and browned and were full of tiny black seeds. These seeds became our first collection.

Blueberries, (Vacinium sp.) with their sour notes of blue, are packed with 20-30 seeds per berry. There are subtleties in the varieties of blueberry — the bog and dwarf blueberry are smaller, and sweeter than these traditional, larger wild blueberries. Vacinium alaskensis are abundant in this forest, pops of blue and purple carpeting the forest floor. And they were our second collection.

Foamflower (Tiarella trifoliata) keep their seeds close. They go to seed so quick, it is easy to miss the event: tiny white clusters of flowers that, when blooming, look like mini constellations of stars mirrored onto the forest floor, elongating into seed pods, each filled with sometimes three or five, but more often one, single black seed.

By and large, this month was berry month.

Devil’s Club (Oplopanax horridus) are bright, flat umbrellas of green. Their stems are full of sharp spikes, and they balance large triangles of red berries atop their leaves. Bears relish them; we take a few from every plant we can get close to.

Salmonberry (Rubus spectabilis) pack themselves tightly into stream systems and along roads and trails. This month, droplets of plump berries hung from their branches, coming in colors gold, red, or sometimes a combination of both. They taste like water, but bitter too.

And the Fireweed (Chamaenerion angustifolium) — the most vibrant shade of purple-pink you will ever see, brightening the road systems and stitching up the slopes of tall mountains. We collected their seed pods just this morning — sleek and slim green-bean-like capsules, pink on top with a green underside, each filled with up to 8,000 seeds. Abundance.

Stink Current, Ribes bracteosum, leaves your hands smelling of lemon and mint. These delicacies became our most recent collection.

It is clear that each plant and their seeds are exceptionally designed to work for them, their morphology, their pollinators, their eventual dispersal. Everything about them is carefully and thoughtfully designed. They produce seeds of their own making.

After harvesting comes drying, sorting and cleaning the seeds for storing. This is a tedious process, one that is also all about detail and care (especially when everything is soaking wet!).

As seed collectors, we are one mode of transport, one of these plants’ dispersal units. In the process, we try to ensure that we are leaving enough behind for the bears, for the birds, for the plant’s own survival and promise of future generations. If we take, we must also give back.

Seeds are gifts from the earth. They are plentiful, but they are also limited — a resource we collect in the case of needed restoration, which is also plentiful.

Joy and sorrow. Seeds are delightful.

On a walk down a trail at the end of a long day, exiting dense stands of red cedar and western hemlock, just entering a muskeg, there, delicately dropped in the middle of the trail: a speckled eagle’s feather. An offering. A delight.