I had a teacher once who told me “seeds are everywhere.” They just don’t take root everywhere.

Working on the Tongass, living on Lingít Aaní (Tlingit, pronounced “KLING-it”, Land) has meant many things. I have witnessed how deeply rooted harvesting and foraging is in Alaskan culture. I collected seeds and learned that this ancient practice is one that joins science and art. I grew to understand how variable a plant’s phenology can be — how unpredictable and essential an act it is to pass on genotypes, pass on restoration, pass on seeds through generations.

Seed collection is an intimate act. Over the past months, I worked largely on the microscopic level — leaning through understory to discover the smallest of berries or fixing my eyes on the ground to notice the smallest of flowers, straining my eyes through a hand lens or cleaning seeds by hand invites you to zoom in even closer. With some plants, like the pungent and prickly Oplopanax horridus (Devil’s Club), this intimacy is difficult to achieve, often requiring two people to get close to the plant — one to climb up high and bow the toppling head of berries down near enough for the second person to reach up through the spikes to strip the berries into a bucket. Days collecting Devil’s Club left us with torn clothing and smelling of celery and rainforest. We took, and so did they.

This intimacy extends beyond the collection and into the entire process. During the planning and scouting phases, we paid multiple visits to the populations we anticipated collecting from, tracking their phenology and guessing when they would go to seed. Many times, we thought we had it planned and predicated exactly right, that we were tuned into their growth and timeline. Then when we arrived to collect from them, they’d fooled us — gone to seed within a span of a few days or a week. Their seeds were not for us.

I found that small acts of intimacy were present all over the Tongass, including interactions between strangers in town. The District Office here sits on the rock cliffs above Bar Harbor, along with the bunkhouse. I spent many evenings on these docks, growing accustomed to the wobbly walk and coming to know the names of certain resident boats and fishermen. One evening, a stranger handed me a bouquet of fresh herbs — English thyme, rosemary, Japanese kale. He reached down to collect the herbs for this spontaneous gift from the variety of potted plants trailing off the side of his boat as he paired down his deck garden for the colder months. We exchanged smiles as the plants passed from one hand to the other. I shared my gratitude.

This is not the first time I am writing about gifts during this internship. In an earlier post, I spoke about the delight of seeds, how they are like small gifts from the earth. In my first post, I wrote about abundance. I have found both here on the Tongass — gifts and abundance.

Yet this season’s seed collection comes at a time where native plants and their seeds are growing increasingly scarce, removed from the land by people, infrastructure, hot and widespread wildfire, eroding streams and drying wetlands. I witness abundance; I also think about the gradual loss of habitat and native plants on this planet.

This is why we collect. Native seeds are gifts for the future.

I was introduced to so many plants while I was here. Many were strangers who I gradually developed a relationship with. I tracked their phenology, gathered their fruits, cleaned their seeds. They signaled cues of growth, gave up juicy berries that painted my jeans in smears of red and purple, offered their seeds.

We collected 1,577,772 seeds, that is, 17 pounds of seed from 17 species and 23 populations, ranging across southeast Alaska’s rainforest, lakeside, alpine, and muskeg ecosystems. Six of these populations will be stored locally at Ketchikan Misty Fjords Ranger District. The remaining 17 we labeled, packaged and shipped to Bend Seed Extractory.

We were able to restore and recover 2 miles of salmon habitat on two streams. Some of the seeds we collected this season will return to those stream banks in years to come. It feels good to know where a handful of the seeds we collected are going.

We collaborated with other departments, expanding our experience beyond Botany and seed collection. With Timber, we visited micro- and macro- timber harvest areas and surveyed for rare plants. With Recreation, we hiked-in wooden planks to repair a bridge and helped maintain local trails. With Fish and Wildlife and Ketchikan Indian Community, we dug trenches and hauled logs into stream beds with winches, blocks, and tackles. With Archeology and Landscaping, we hiked into cabin-building sites and assessed the area for archeological evidence, probing the ground for charcoal and remnants from the past.

This exposure to other specialties in the Forest Service was eye opening and so much fun. It also interested me to think about the diversity of habitats and species seed collection will impact. Sometimes it is seed that will go into the soil of a major bird migration route or a seed mix specifically formulated for riparian areas (one of the goals through seed collection here on the Tongass). Sometimes it is seed going into steam banks, supporting soil stabilization and spawning salmon. Other times, the seed goes toward grouse habitat, maybe even city parks.

Seeds will be everywhere.

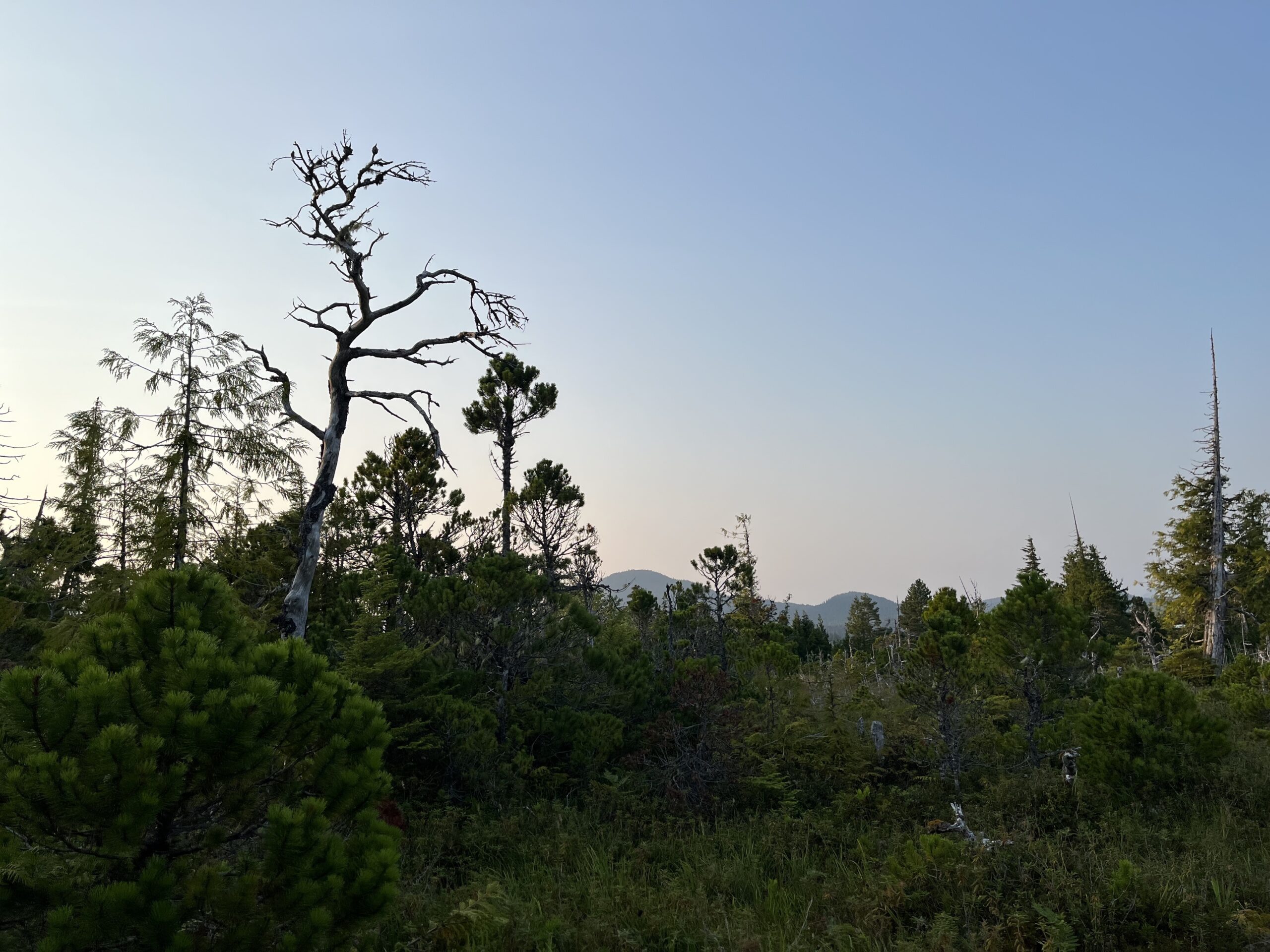

Alaska, I love your silvery blue mornings. Your fog and rain. I love the smell of red cedar. I love watching the shore pines bathe in the wideness of your sky. I love your islands shrouded in clouds that break up the ocean’s vastness. The bouncing, soft ground of moss beneath my feet. The eagles, bears, salmon, deer. How the people here live closely to the land — hunting, foraging, fishing, gathering. The pace of life in Ketchikan slows over winter and expands in the summer. Locals almost hibernate, before spending their summers out at sea or, in our case, in the forest.

I have learned, while being here that humans can live in pace with the seasons. And some of our greatest teachers in this lesson are extraordinary adapters: the plants. Their chance of survival is so slim, conditions are varied, places are packed, and so many of our current land practices adversely impact their ability to take root.

Seed are everywhere. And sometimes they do take root. They are small, but meaningful. And so, we collect.

I have completely fallen in love with the process, the plants, and the people.

Thank you, Alaska, for your many lessons. I will carry your seeds with me, everywhere.