Driving up from the Central Valley of California, I was struck by the rapidly changing landscape as I wound my way up Highway 50. Already, I knew I was lucky to work here for the next several months. Not only was I met with gorgeous views, I noticed a remarkably cooler temperature, feeling grateful to escape the almost-one-hundred-degree heat back home.

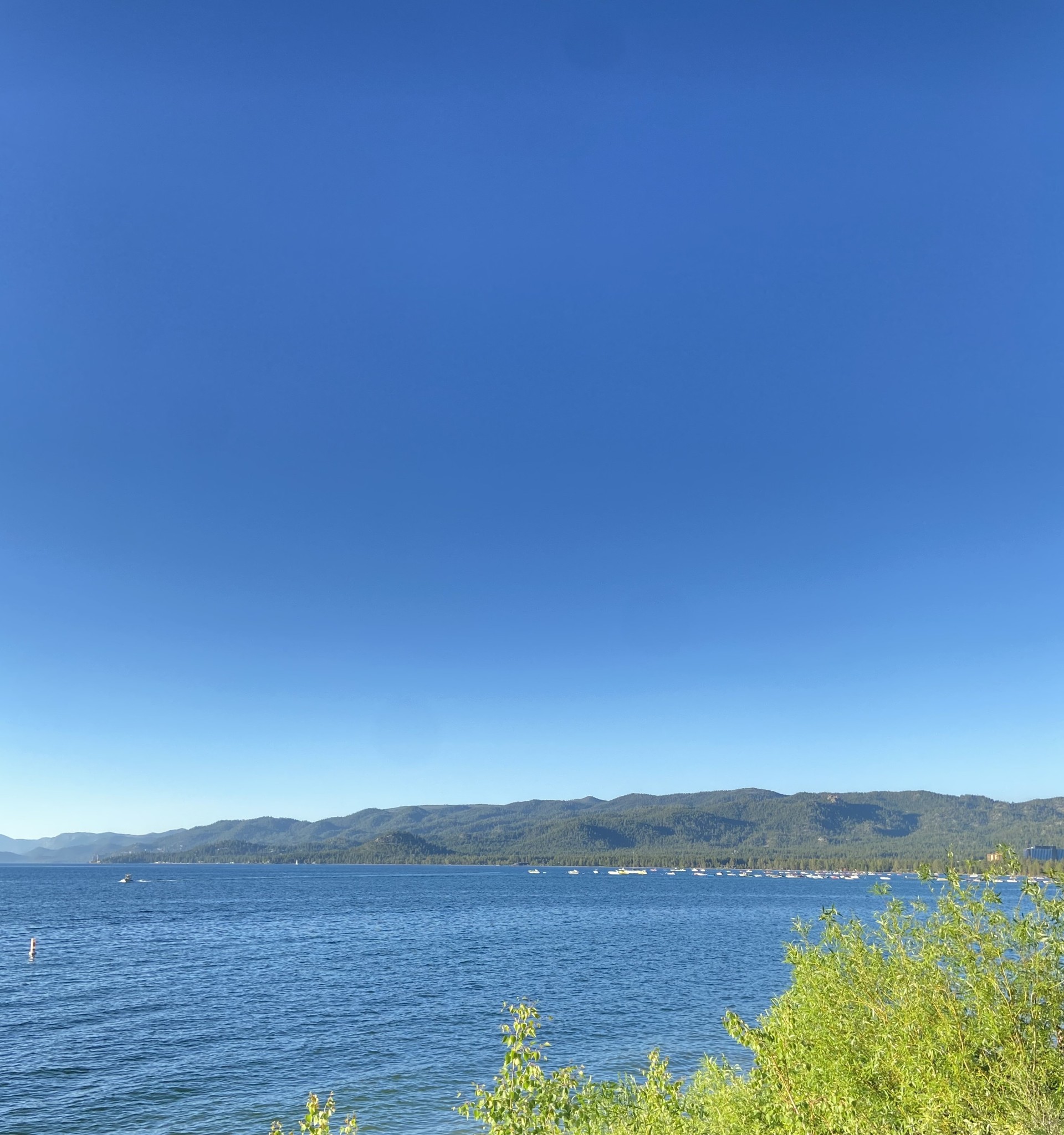

Lake Tahoe is nested within the Tahoe Basin, surrounded by peaks on all sides. At about 6,500 feet above sea level, the Lake Tahoe Basin Management Unit is where I will employ, hone, and develop my skills as botanist.

Almost immediately, I began exploring the flora of the Lake Tahoe region, expanding my collection of iNaturalist observations. Being at a such a high elevation, this area can support plants unique from the lower, hotter, and drier areas to the east and west. Some of my favorite sightings of native plants include Scouler’s St. John’s wort (Hypericum scouleri), white bog orchid (Platanthera dilatata), Washington lily (Lilium washingtonianum, although it was not in bloom), and Oregon checker mallow (Sidalcea oregana). The majority of these were found growing in meadows or along streams. The Washington lily, however, inhabited a very sunny and dry slope.

A lot of my time in the field so far has been spent remediating introduced species invasion to reduce their impact on native flora and their habitat. One of the particularly prolific species is bull thistle (Cirsium vulgare). Bull thistle tends to grow in damp areas–in the vicinity of streams or in wet meadows. The preferred treatment for this weed is manual pulling, with a hori-hori making sure to take as much of the thick taproot as possible. If a plant begins bolting or flowering, the inflorescence has to be cut, bagged, and tossed in the garbage. Its sharp spines make leather gloves absolutely necessary. A native look-alike species, Anderson’s thistle (Cirsium andersonii) looks extremely similar, and I spent some time learning to distinguish the two. For one, the flower head is vase-shaped in bull thistle and cylinder-shaped in Anderson’s. The leaves on bull thistle are much rougher and its stems grow spines. It is also very helpful that Anderson’s thistle usually grow in drier locations, so the two species often don’t overlap.

Toward the end of the month, me and Kendall, my co-intern, have begun preliminarily checking out seed collection sites, and I am especially looking forward to doing more work with the whitebark pine. I hope there is much to update about this in the future.