With my season nearing an end, my co-intern and I are putting the final touches on processing our seed collections from the past month. Although we still have a few more populations to visit, we successfully collected seeds from seven of our high-priority species across 25 sites. These include Achillea millefolium, Bromus carinatus, Elymus elymoides, and Eriogonum umbellatum.

We also had the chance to collect seed from two unique species. The first was the Washoe tall rockcress (Arabis rectissima var. simulans), a critically endangered member of the family Brassicaceae. The location for this population is slated for parking lot construction as part of a bike trail along the east side of the lake, so we received permission to perform a salvage collection which will be used to seed the surrounding forests. We collected at least 62 grams of seed for this species, despite their incredibly small size (1-2 mm each).

Tahoe yellow cress (Rorippa subumbellata) was the other unique species. This Brassicaceae only grows on the shores of Lake Tahoe, and a lot of effort has gone into its conservation. We recently visited two populations in hopes of collecting its pods, but the majority were still maturing. We plan to return a week from now, when the seeds will most likely be ready. One consideration we had to make was avoiding its look-alike, the curvepod yellowcress (Rorippa curvisiliqua). Fortunately, the fruits of the two species look very different.

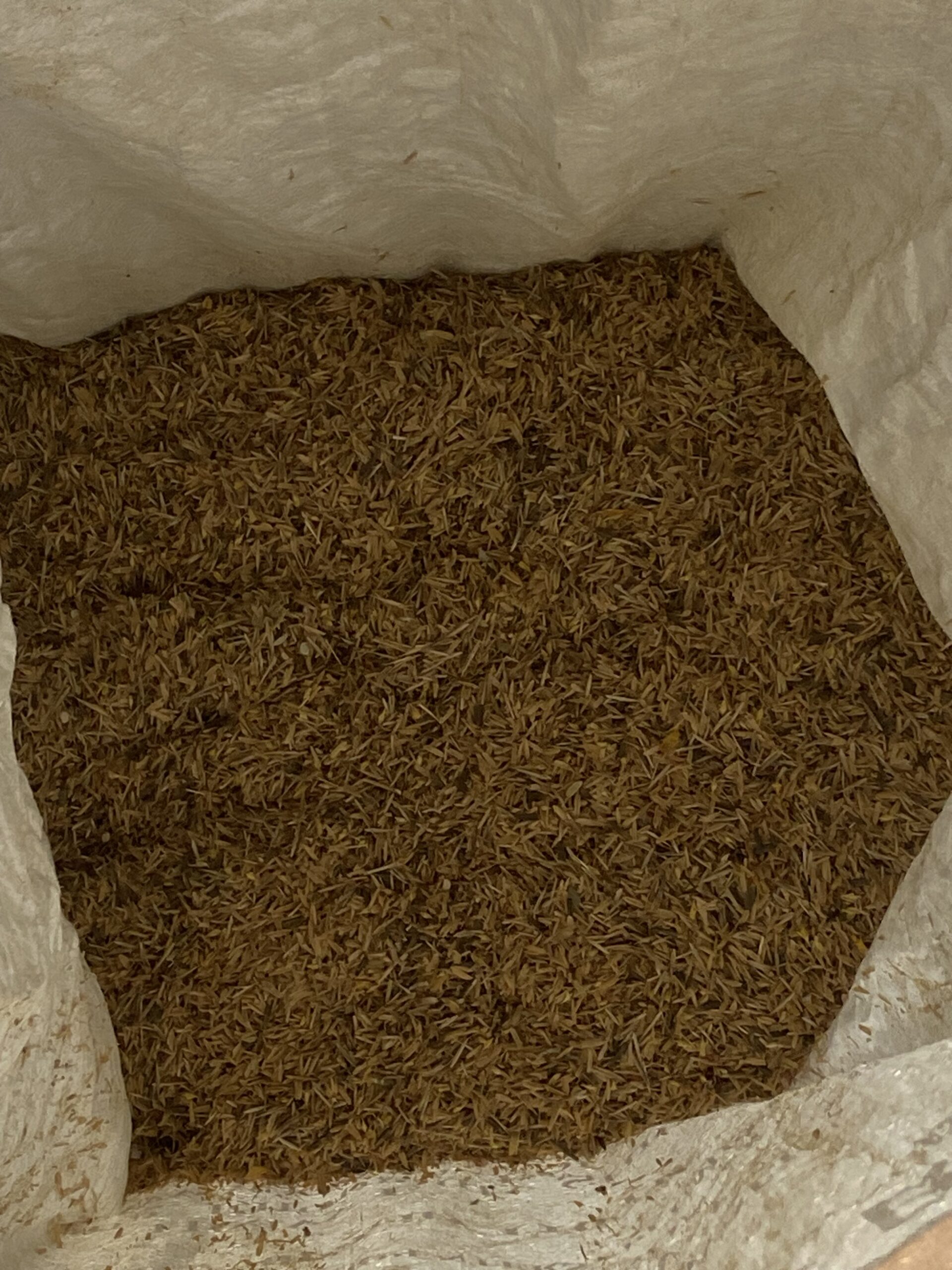

Using seed collected from previous years and purchased from a local native seed vendor, we are in the process of putting together seed bags to be used for revegetation at Incline Lake. This is a manmade lake from the early 1900s that was a popular resort and vacation spot and is now being restored to its original meadow habitat by LTBMU. Each seed bag will cover a quarter acre and includes specific weights of seed from seven different species. Soon, we will use these bags to continue previous years’ work in seeding restored landscapes at Incline Lake.

As always, I take the opportunity to appreciate the beauty of the area, especially when I get to climb up high for a bird’s-eye view.