September has really started to feel like fall. Skeletons and ghosts are showing up in people’s yards. The greens have started to fade to gold and orange. The mornings are crisp, and the days are getting shorter, which has made making waking up much harder but has also resulted in seeing some beautiful sunrises.

This month has been full of seed collecting. We’ve continued to collect berries, and one of my favorite’s has been mountain ash, Sorbus scopulina. To me, the bright orange berries seemed to have come out of nowhere. Two months ago, the drainages and damp hills were a web of dark green, but now the mountain ash berries peek from the foliage and look like little gems in the sun.

Another fun collection has been rabbitbrush, or Ericameria nauseosa. It grows as a shrub in exposed and dry areas. It blooms a golden yellow, and as it goes to seed, turns fluffy and white from the pappus (hairs) on the seeds. It is fun to collect because it is easy to get a lot of it! The shrubs are fairly large and produce a lot of seed, and usually many shrubs grow together. In one day, Eliza and I ended up with a haul of thirteen bags!

In addition to seed collection, Eliza and I got to help with a whitebark pine survey at the Lost Trail Ski Resort. Whitebark pines (pinus albicaulis) are a threatened species that grow at high altitudes. The ski resort proposed new ski runs and lifts, and our job was to count the number of whitebark pine in the area to help them manage the new developments in accordance with the guidelines for threatened species protection. Whitebark pines have five needles per bunch (fascicle), which is how we could tell them apart from lodgepole pine, which also grows at high altitude but only has two needles per fascicle. Most of the trees were small, less than five feet, and blended in with the lodgepole seedlings, but we counted over 100 trees in about 10 acres.

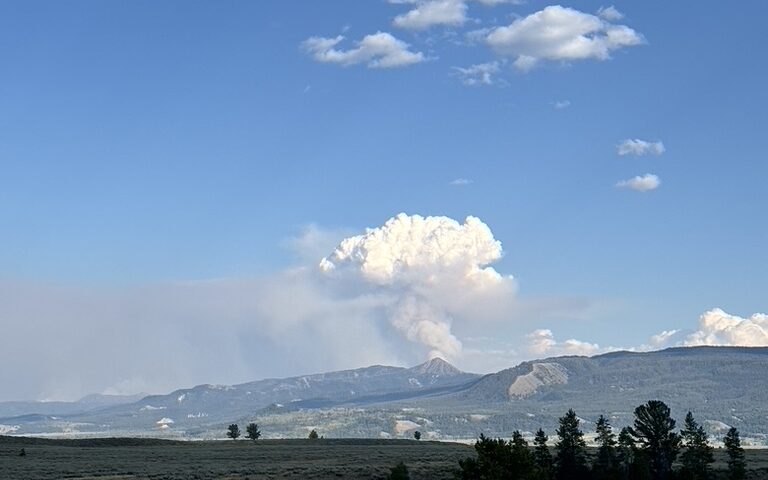

Something that has been less exciting about September was the smoke. There were a few fires in the Bitterroot Valley that made for a very smoky couple of weeks. It was a bummer to look outside and not be able to see the mountains across from us. The smoky days felt somewhat like rainy days because we were stranded inside, but they were not at all cozy. Fortunately, we were out of town and (less fortunately) staying home with COVID for some of the worst of it. The benefit of the smoke was that when it cleared, I had a renewed appreciation and awe when seeing the mountains.

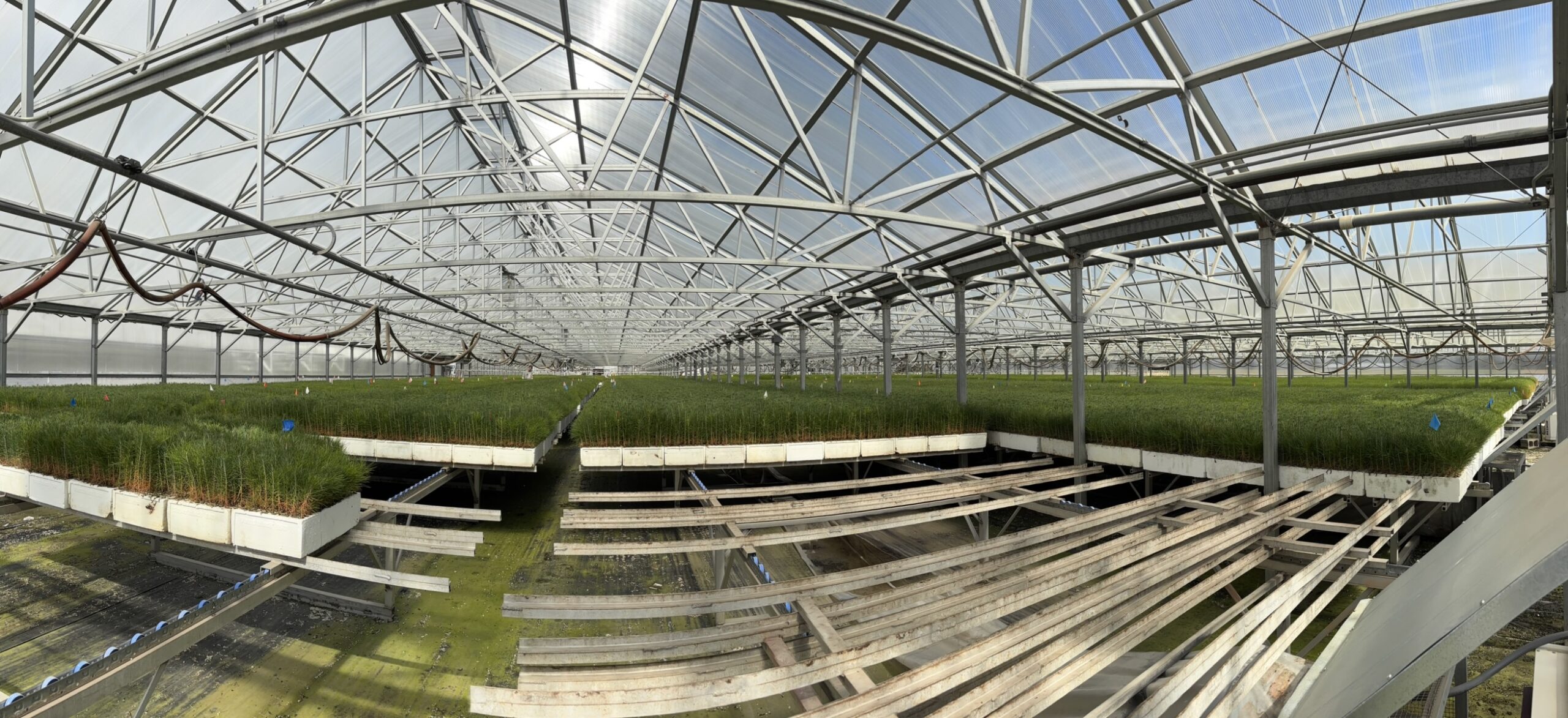

This past week, we went to Coeur d’Alene to visit our region’s nursery. It has been really cool to see how our seed collections are used. The nursery had rows and rows of plants being grown out for seed transfer zone studies. These seed transfer zone studies compare morphological data to find patterns and delineations between populations that then become seed zones. This is important because seeds taken from one place within a seed zone will likely grow well (and be well adapted) when planted in other parts of the seed zone. They also grow seeds out for seed increase, meaning they use wildland seed collections to grow plants, then collect seeds from those plants, increasing the total amount of seed from that population or species. Nathan, the seed transfer zone manager, told us that often with the wildland collections start as a handful of seed, but after the seed increase plantings they collect pounds and pounds of it.

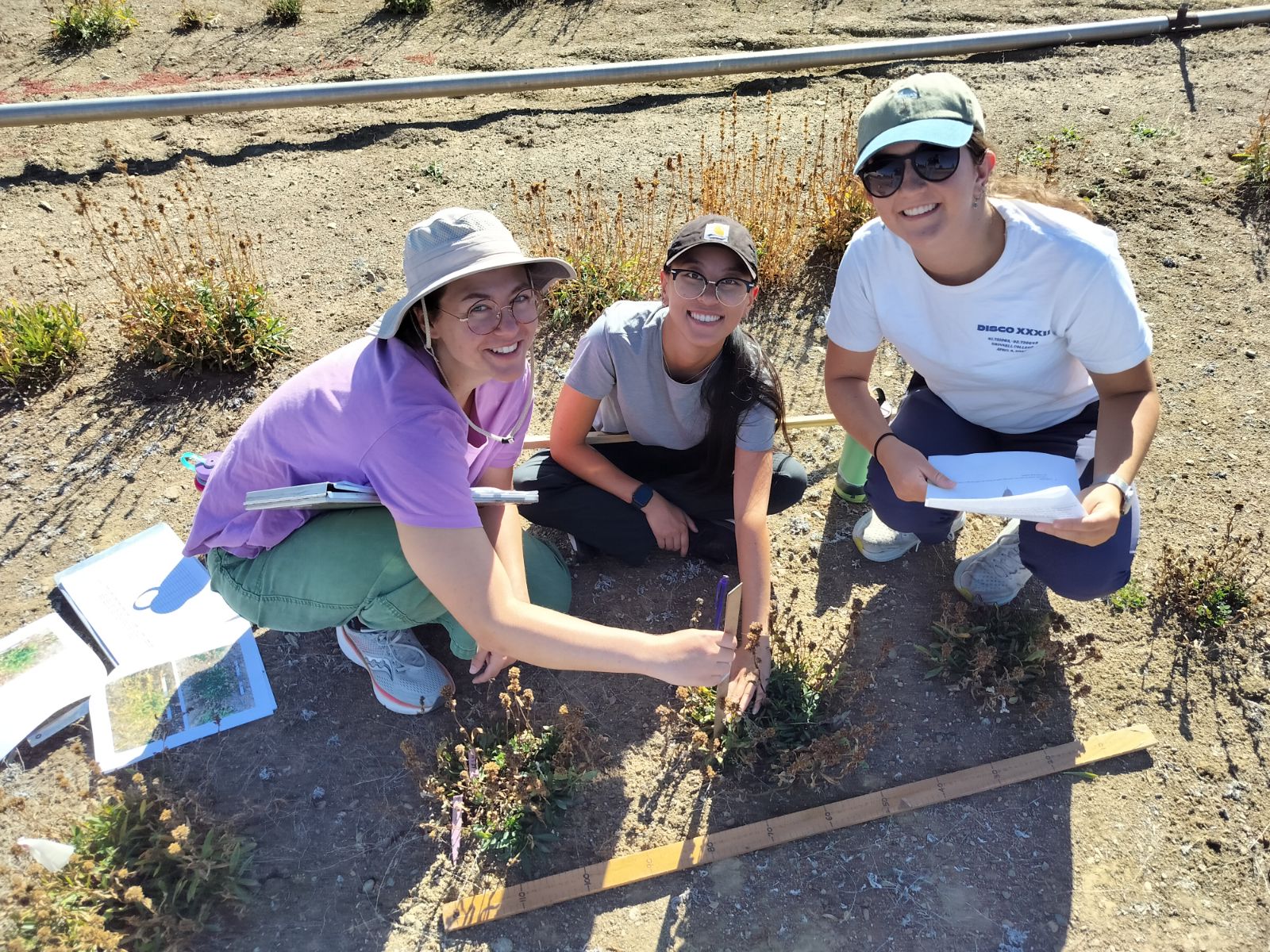

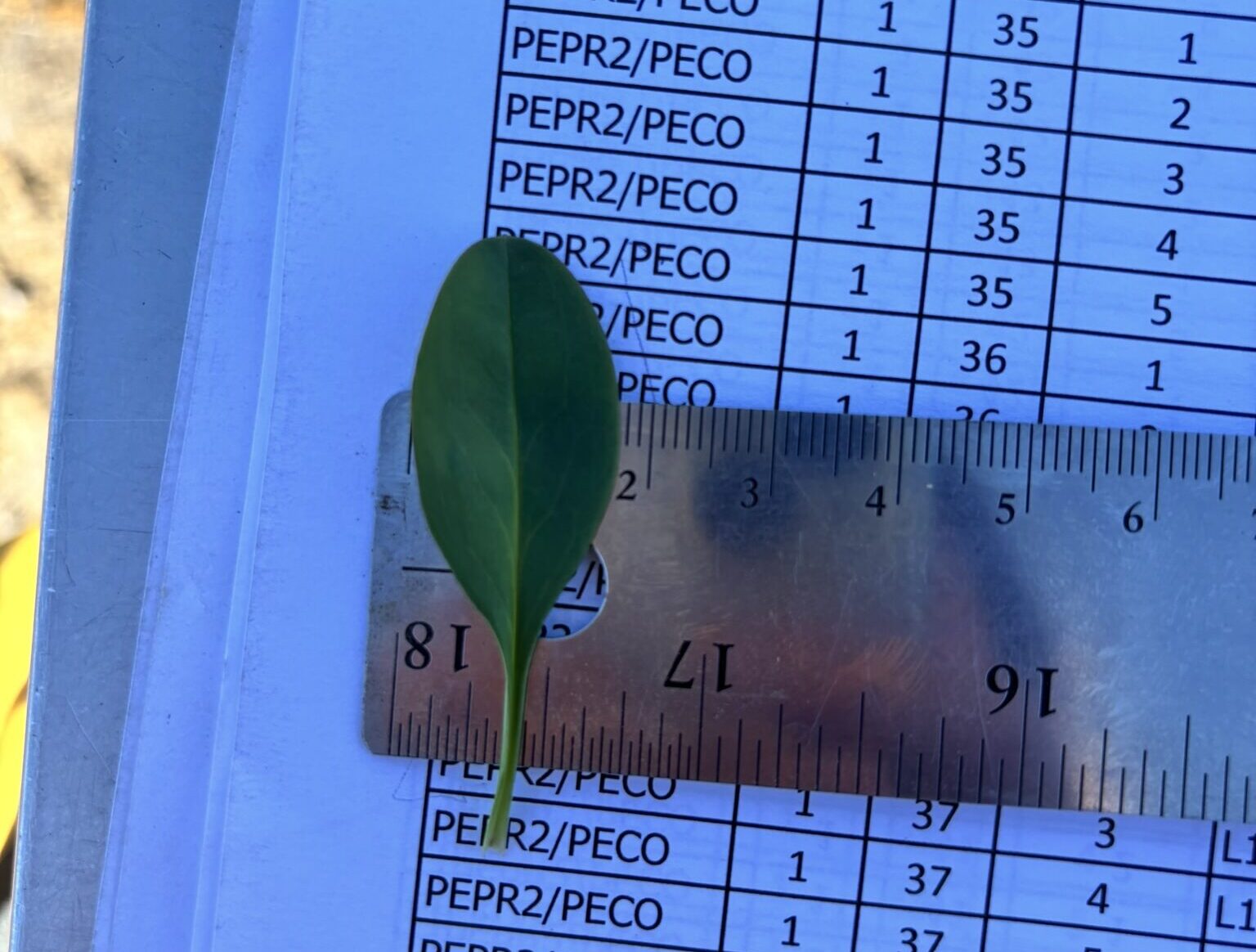

Our job at the nursury was to measure a ton of Penstemon procerus plants. There are four rows that are called “repetitions” and one row on each side to act as a buffer to prevent any outer rows from experiencing an edge effect. For our measurements, we assessed overall plant vigor, counted flower heads, measured the overall plant width and basal leaf height, and measured the dimensions of an average leaf. After about 10 plants I realized it was going to be a long day of sitting on the ground, bending over plants, and counting.

The work was very repetitive, and Hannah and I tried many things to make the work more exciting and comfortable. We played music, found different things to sit on, had reward cheez-its, and made up different stretches to ease our aching backs. Despite the tediousness, it was satisfying to get more efficient at the measurements and see us slowly creeping towards the end of the row.

Another major operation in the nursery is to grow conifer seedlings. The nursery receives 3000 bushels of cones each year that they process, store, and save for future planting. To extract the seeds from the cones, they dry the cones over kilns. Once the cones are dry, the scales open and the seeds easily fall out. The seeds are stored in barrels and kept in a freezer until they are grown out in the greenhouses. According to Nathan, they have enough conifer seeds stored in freezers to keep producing 5 million seedlings a year for 10 years!

The nursery greenhouses are full of baby trees that come from the processed cones. In total, they grow around 3.5 million trees every year, which are then sold to be planted in the forests again. One of the trees they grow is whitebark pine, around 150,000 seedlings each year. Nathan said they are difficult to grow, as they are slow growing, don’t germinate well, and are very sensitive to heat.

In addition to growing whitebark pine seedlings, they’re also breeding resistance to whitebark pine blister rust. They collect and sow seeds from “parent” trees that appear to be resistant to the fungus. Then they expose the offspring to blister rust spores (10-20x the fungal spore amount than they would be exposed to in the wild). The percentage of blister rust resistant offspring determines the strength of parent tree resistance. Highly resistant trees are then bred with other trees to increase the number of blister rust resistant whitebark pines, hopefully slowing their decline.

Time seems to be moving much faster the longer I am here, and I can’t believe I’m approaching the last month of the program. I continue to learn so much and I’m looking forward to more seed collections, another visit to Coeur d’Alene, and more whitebark pine surveys.

Cicely