Eliza and I are ending our term in one week. October has been the quickest month of all. It started by saying goodbye to our co-intern, Li, and finished with matching alien Halloween costumes. Now, snow covers the tops of the mountains, and the fall leaves lose their last bit of color. Despite the turn towards winter, there was still a lot to do this month.

At the beginning of October, Eliza and I went out with hydrology to do water sampling. We drove out to this little creek on some private property. We hiked to a shallow creek that flowed through tall grasses and shrubs. To set up our equipment, two people ran a tape measure across the stream while the others set up the probe and the flow-measurer, which was this fancy-looking stick with a fan on the end. We measured the depth and flow across the stream, and recorded temperature, pH, and dissolved oxygen levels.

By measuring the flow and the depth, the hydrologists can calculate the water discharge. The water samples are tested for nutrient levels, which when multiplied by water discharge, shows the pollution effect on the Bitterroot River. depth x flow = discharge discharge x nutrient levels = stream’s pollution effect on Bitterroot River

Streams have a total maximum daily load, which is how much nutrients can be in a stream and not harm the wildlife and plants. So, by measuring the nutrient levels, depth, and flow, they can determine if the total maximum daily load is being exceeded.

After using the fancy probe, we took two water samples. The samples are sent to a lab and tested for nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus. One water sample was taken straight from the creek, and the other was filtered. The filter removes the particulate nitrogen (nitrogen attached to sediment or organic matter) and leaves any dissolved nitrogen.

The dissolved nitrogen is more readily usable to organisms than particulate nitrogen, so its effect in the stream is greater. This means knowing the total nitrogen levels (unfiltered sample) and the dissolved nitrogen levels (filtered sample) is important to tell the whole story.

We also learned that phosphorus is often attached to particles in the stream bed, whereas nitrogen is more often dissolved and easily flows downstream. This means if a stream is being polluted at one location (dumping sewage or agriculture runoff), the high levels of nitrogen and phosphorus can have different effects. Because nitrogen is less “sticky,” it can cause more issues downstream than at the source of the pollution. Because phosphorus is “sticky” it can accumulate at the source of pollution, and can’t be washed away.

Another cross-training we did was a soils survey for a proposed fuel break. For the survey, we walked along a transect line and dug a hole every 200ft. In the hole we recorded the top layer (duff, moss, bare soil), and the presence of roots, charcoal, rocks, and mycorrhizae.

Andrea, the soils technician, also needed to determine the soil texture. She would feel the dirt and declare it as loam or sandy loam or even silty loam. The way she described learning the soil textures reminded me of the way I’ve learned the plants here. After feeling the soil so many times, she developed a sense of what each soil type feels like without being able to articulate it explicitly. This is how I feel about distinguishing grasses or Asteraceae species. When I see them, I know who they are (or at least who they are not), but when I try to describe the leaf blade angles or the shape of the bracts, the differences become hard to explain.

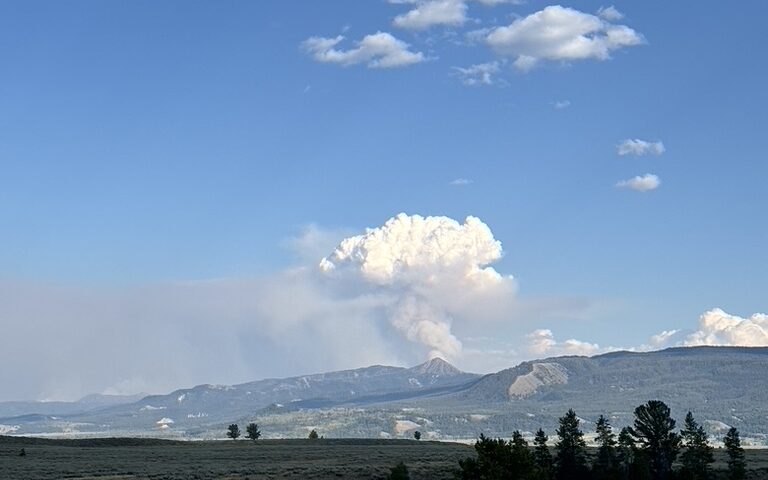

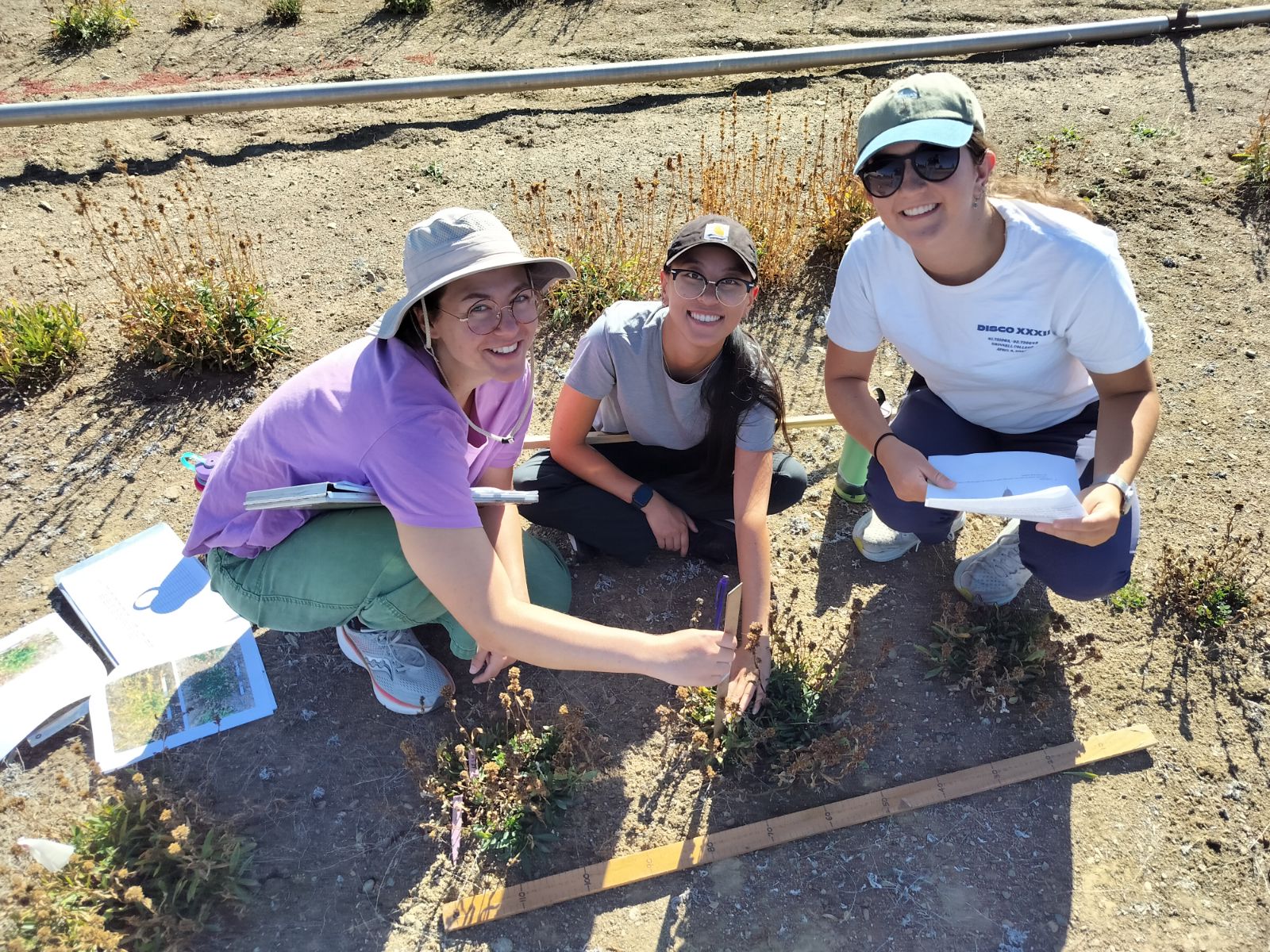

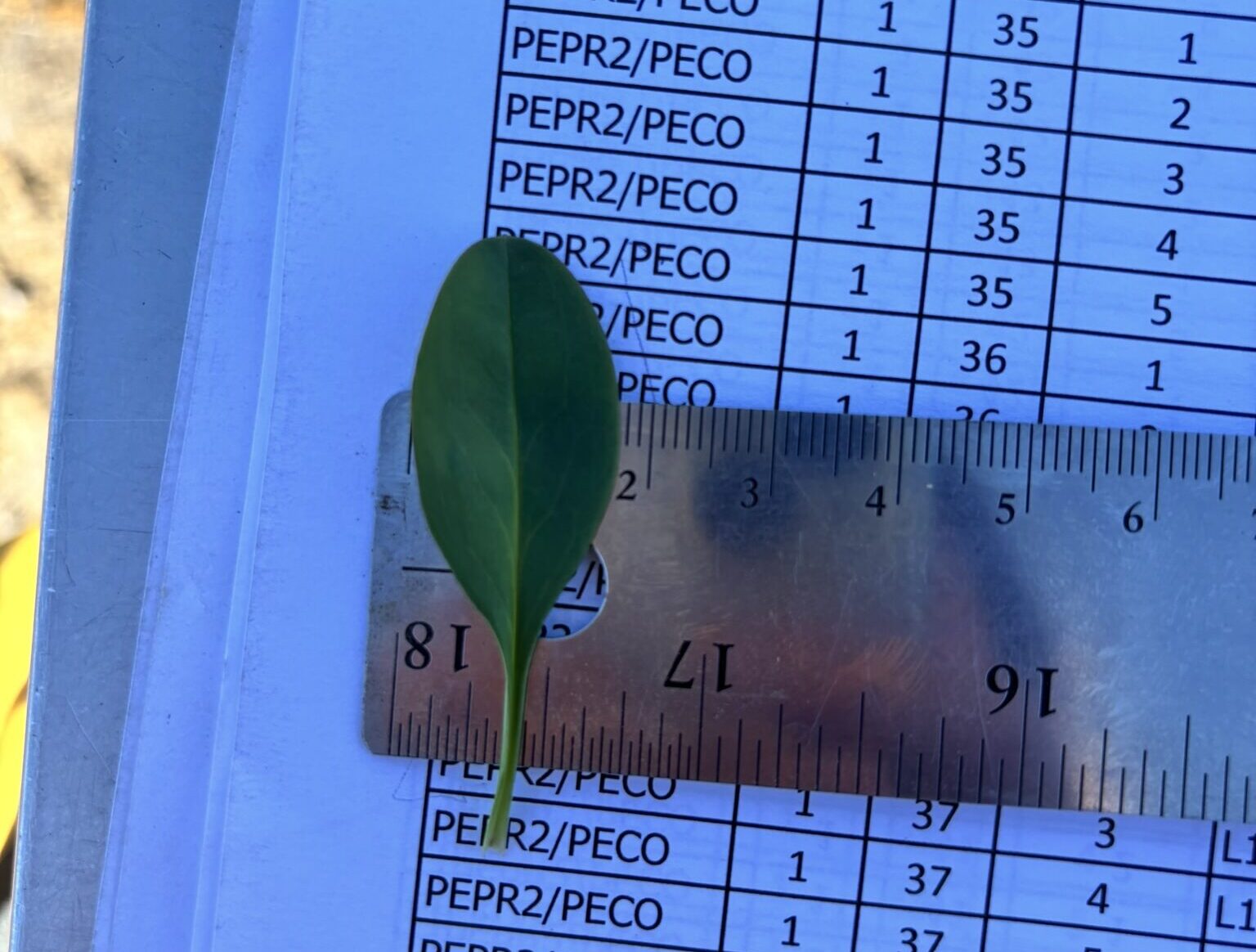

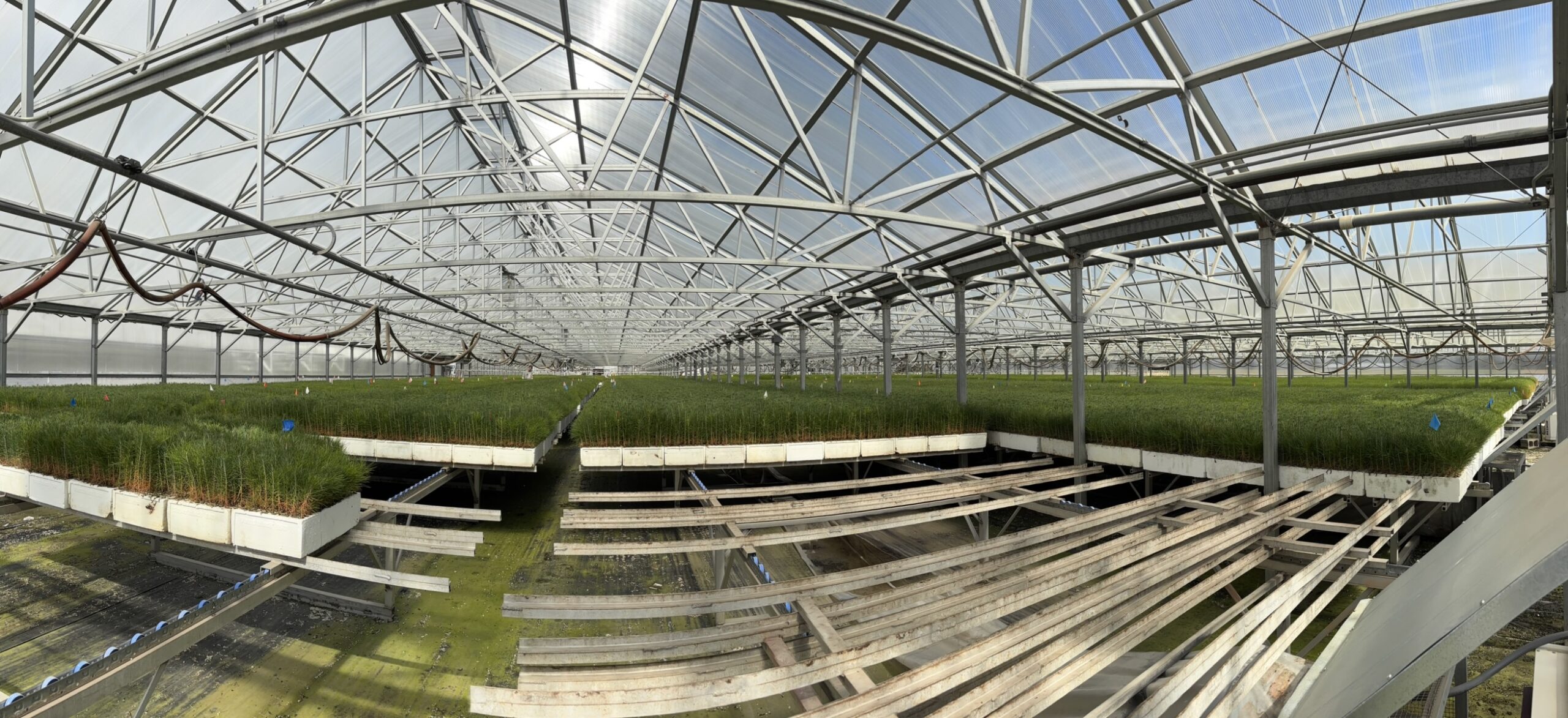

With Botany, the last weeks of October have been dedicated to planting pollinator islands. The area where we established the pollinator islands burned in the Trail Ridge wildfire in 2022. Right now, it looks quite destitute with blackened trees and bare soil, but apparently, bumblebees like to make their nests in areas with exposed soil and downed trees. However, the bees need a food source, and currently, the vegetation is lacking. So, the idea with the pollinator islands is to provide food sources in areas where bees might like to nest.

In each pollinator island, we planted 188 plants. We used hoedads, which is a tool I had never heard of but made the planting fairly easy. Unfortunately, in the past, the plugs haven’t always survived very well. In order to find and track plug survival in the following years, we measured each plug’s distance to the center and the azimuth. This was a lot of measuring, but I got much better at using a compass!

However, during this project, we were racing the season change. The temperatures were dropping, and we wanted to get the plugs in the ground before it froze. We encountered two snowy days, one of which resulted in having to turn around after enjoying cups of hot chocolate, and the other required sifting through the snow to get the plants in the ground before it was too late.

Overall, I really enjoyed this project. While collecting seed is important, we don’t get to see the positive effects. The work for this project felt very tangible and it was fun to directly change the land.

Our second to last weekend Eliza and I hiked Trapper Peak, the tallest peak in the Bitterroot range at 10,157ft. Its stark silhouette always inspired awe and mystery, and after talking about hiking it the entire time we’ve been here, we were finally ready.

We started at dawn and hiked up with the sun as it rose over the valley below. Soon, the navy sky lightened and the pinpricks of remaining stars faded. We kept passing lookout spots for this wide canyon. At first the view of this canyon was a dark abyss, then it turned monochrome-blue with the morning, and finally, the sun peaked over the Sapphires on the eastern edge of the Bitterroot valley and cast a magnificent fiery light onto the tips of the peaks.

We hiked up and up, removing layers as we got hot from the incline and putting them back on as the altitude sucked the heat from the air. Eventually, we made it past the tree line. The summit was in sight, across a large talus field. We scrambled and hopped across rocks, and eventually made it to the very top.

The view was beyond incredible. We could see everything: the bubbling hills of the Sapphires, the harsh canyons that line the valley, the dense forests of the West fork, and a new view of the jagged peaks that stretched, seemingly forever, to the west. It truly did feel like we were on top of the world.

And what an amazing way to end our experience here, to stand at the peak of the mountain that we have seen almost daily, the peak that towers over the rest of the valley, that seems so grand and inaccessible standing below it. Standing at the top of Trapper, it felt like I was looking at every field day, rare-plant survey, and seed collection all at once. From the top, we could see the entire valley: highway 93, the river lined with cottonwoods, the farms and ranches spread onto the slopes of each side of the valley. It seemed like a perfect place to live.

This experience has been so amazing and I have learned so much. My first week here I was so overwhelmed with moving to a new place and learning so many new plants, but what was strange at first soon became comfortable and familiar.

At first, the dry air seemed to steal all the water from my nose and throat, but eventually, I came to appreciate the lack of sticky summer air that I was used to. At first, unfamiliar shapes and patterns of plants surrounded me. Now I can walk through the forest and call out the names of plants around me. At first, the town of 800 that Eliza and I call home seemed oppressively small, but I quickly found comfort in the simplicity of being a short walk to the grocery store or solitude at the river.

I got so lucky with my co-interns and botany team, and they were such an amazing part of the experience. I am so grateful for my time here and everything I’ve learned about plants and about myself. I will greatly miss the beauty and serenity of this valley, but I am looking forward to being home.

– Cicely

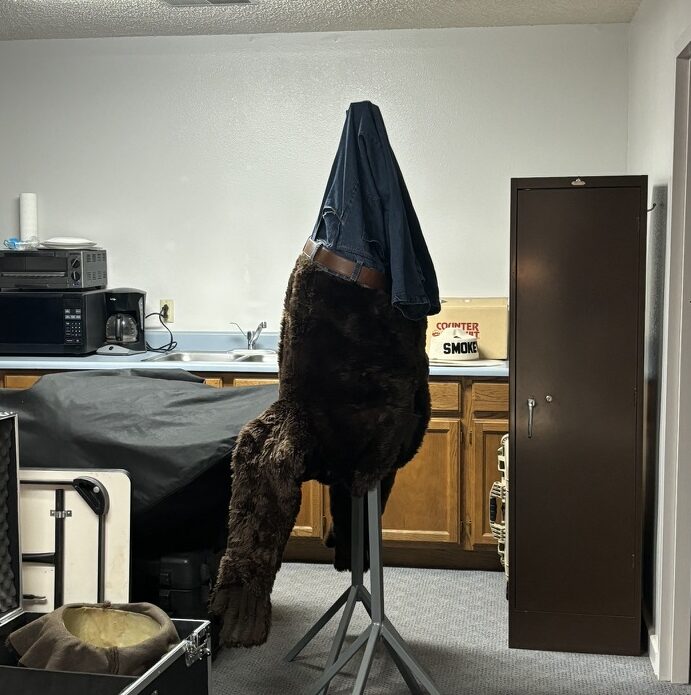

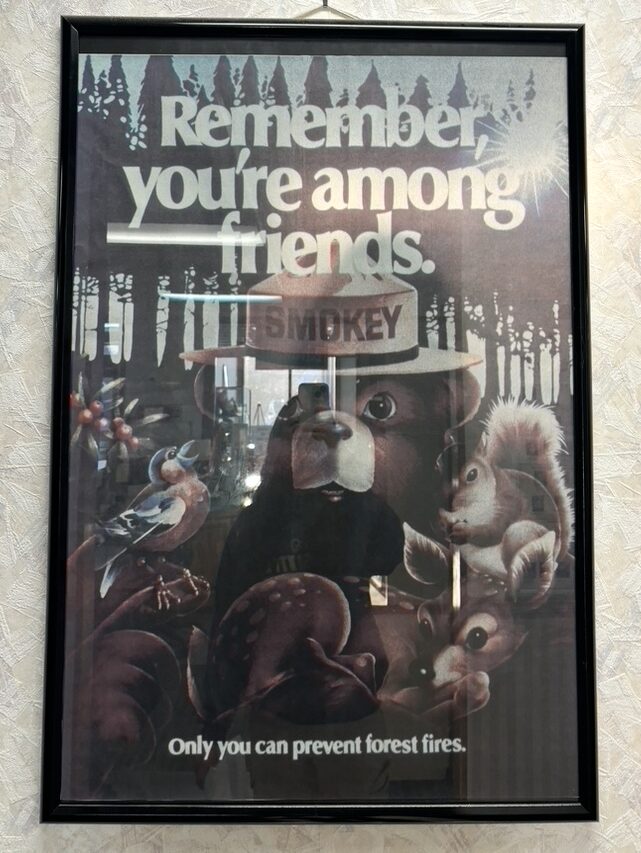

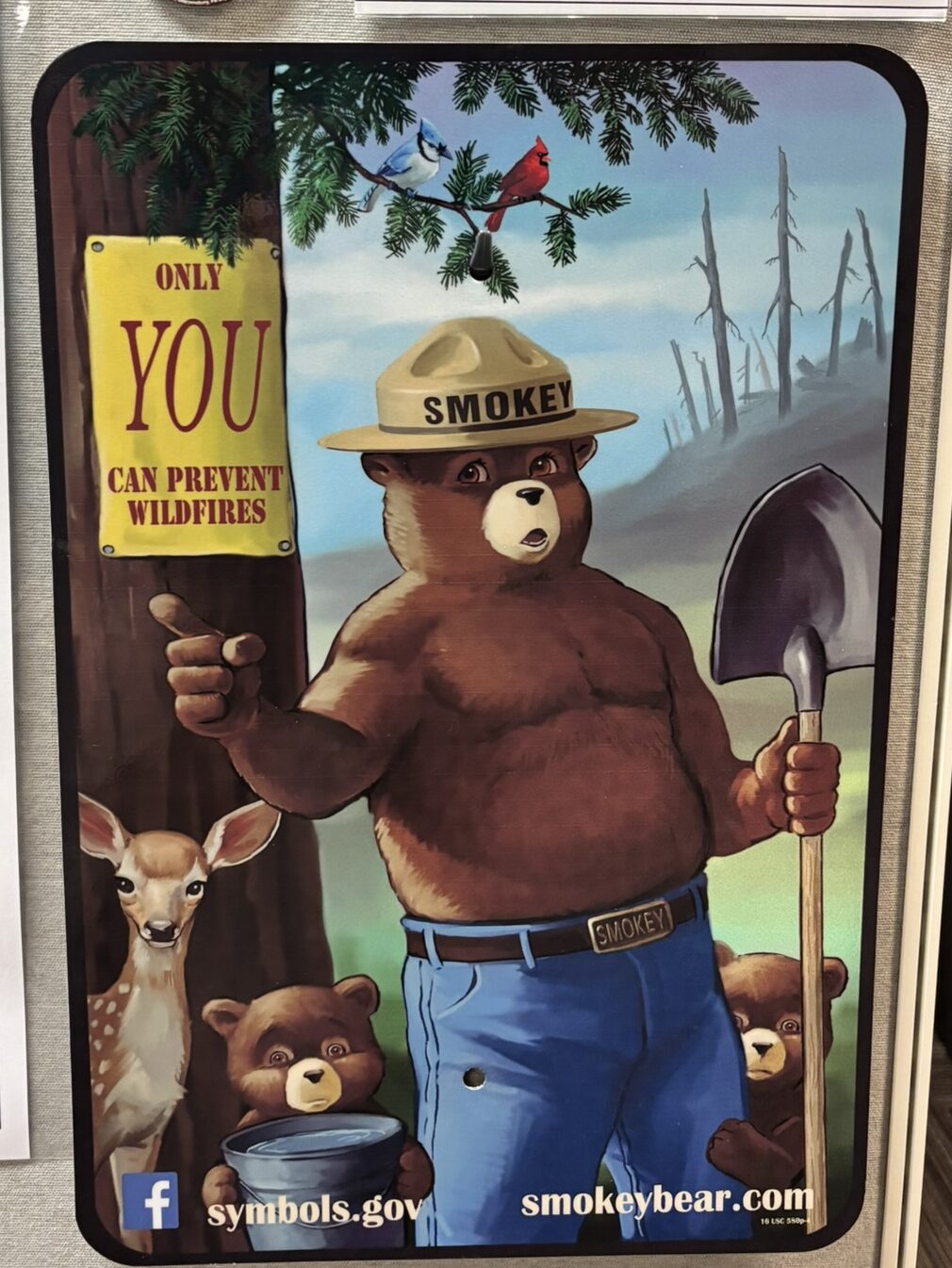

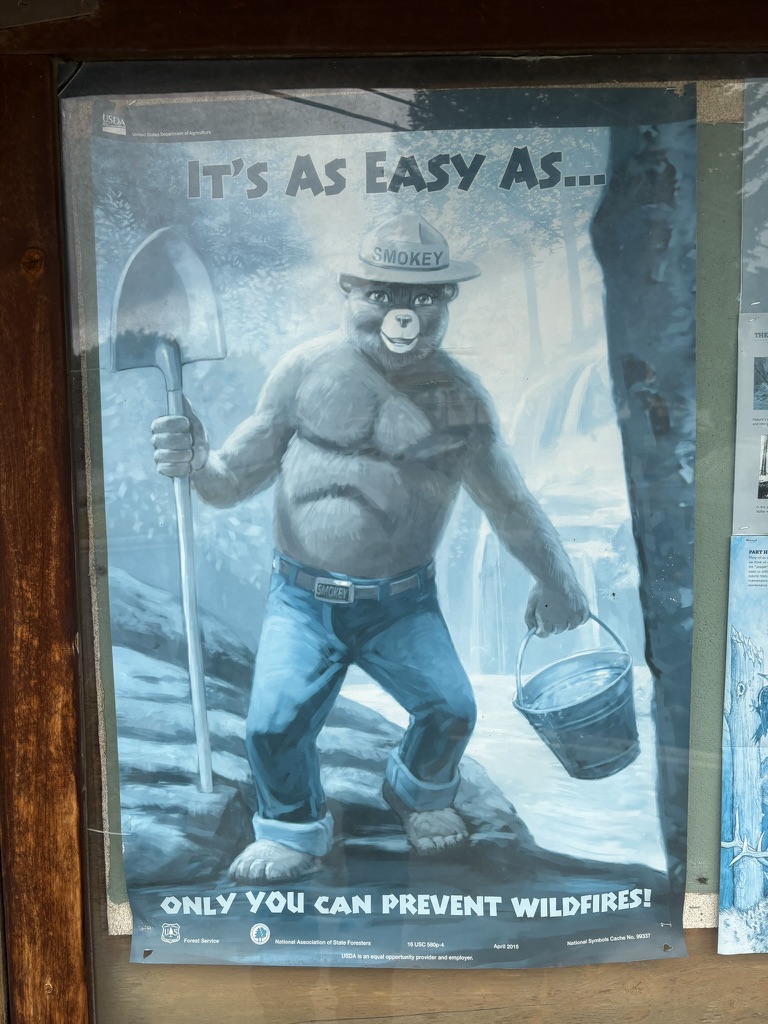

Smokey Collection:

Sunrise and sunset collection:

Plant collection:

Amazing view collection: