After this last month, I’m feeling like a lucky human. It’s one thing to know and recognize a plant during the peak of its life cycle, its blooming state. I liken knowing a plant at this level to a surface level relationship – simple, somewhat predictable, and perpetually showing the most beautiful side of oneself. But these types of relationships often lack depth, complexity, and greater meaning. When you start to recognize and become familiar with a plant after the height of its season, a certain depth of connection comes into being. While some plants carry subtle hints of their flowering stage into their seed stage, they can be quite unrecognizable at first. Like watching a child grow over the years, there’s a stark and raw beauty that arises when you get to know a plant over the various stages of its life cycle. Even when it’s not at the peak of its life and even when it’s in its dried, brown, and withering states.

Gathering the seeds of various plants this season has allowed me to observe them in all of these stages, focusing especially on their later stages. I’ve seen them go from small buds to old dried withered plants in but a few weeks. The blessed cycle of life, from birth to death and rebirth again, happens quickly here. And it’s especially pronounced when your job is to pluck the ripe and ready seed from the withered hands of a dying plant. I enjoy identifying, observing, and working with plants in this latter stage of their life. I think they’re incredibly beautiful in this stage of their life, and I realize how rare it is to interact with them intimately during this season – especially the wild ones. Additionally, observing plants during this stage in their life cycle has made me feel even more in awe of their existence – both native plants in general and, more specifically, their seed development processes. The fact that the seeds from this region of Alaska have the ability to mature at this time of year and then lay dormant through the long, harsh winter astounds me. Especially since, when you cut them open, they aren’t completely dry. They have to maintain some moisture. To go through such harsh conditions as a small living organism is simply amazing.

And it’s not even as linear and straightforward as that. The other morning, we had our first frost. When we went out to gather the seed off of one of our beloved sedges, Carex canescens, the dew had frozen, with tiny icicles clinging to the vegetation. Later that day, it was surprisingly clear, and the sun warmed up everything enough to give me a sun burn. This begs the question: at what point should we stop gathering seed? Since we were inevitably going to warm up the seeds again and they would thaw, at what point does the frost/thaw oscillation begin to wake up a dormant seedling? We decided it was probably still fine to harvest the seeds since, in nature, they would have frozen and thawed anyway. But it got my mind racing with questions about the lives of seeds: how they know when to wake up and how long they can live in the seed state or seed bank before they lose their viability. And this isn’t to mention the grass seeds of this region, most of which have not fully developed yet although it’s almost October! We even saw a grass still flowering last week. What a wild world these plants create for themselves. They truly become more astounding the closer you look and the longer you notice them!

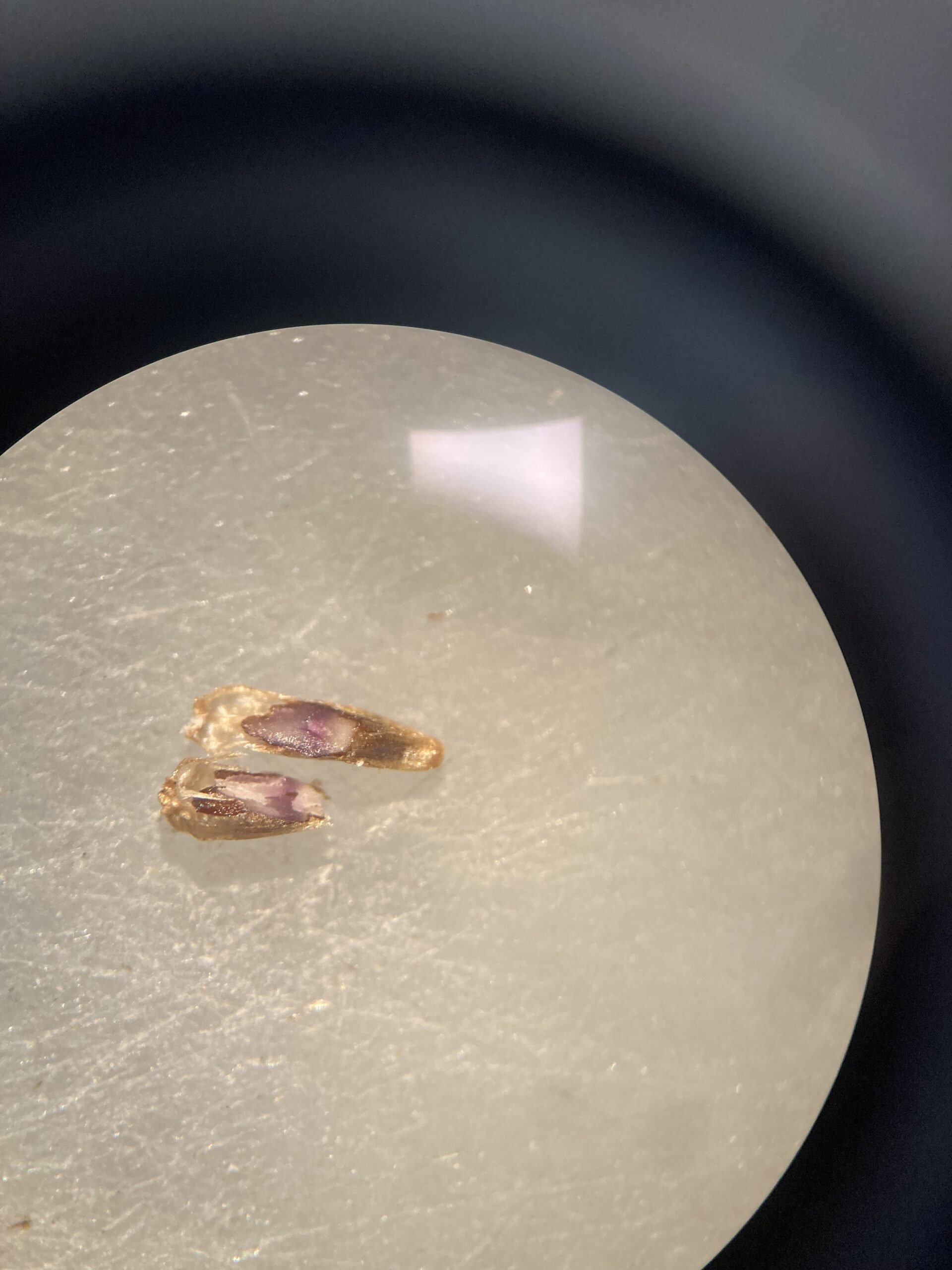

Focusing on and appreciating these lesser known aspects of plants deepens my connection to them and to the greater environment, allowing me to understand the subtle details and differences in their relationship to the whole ecosystem. Sometimes I wonder how many people have formed a close enough relationship with the star gentian (Swertia perennis) to notice how it likes to grow around the edges of the muskegs in south central Alaska and can recognize, just by looking at it, when its seeds are mature. I wonder how many have monitored the transition of the coloring of the megagametophyte of the marsh cinquefoil (Comarum palustre), which blooms curious red flowers in the standing water of marshes in these northern, harsh environments. Who has studied the seeds of Cottongrass (Eriophorum angustufolium) under a microscope and ogled over their sparkly brass seed coat? I wonder how many have had the opportunity to get to know some of these native plants on this level and to this degree. It sure comes with some weird niche knowledge, but being a plant nerd, I take pride in it and am sure it will come in handy at some point down the road. I feel very lucky to have been able to form a relationship with these plants in this way.

At this point, the next stage in restoration process has already begun, and it is exciting to pass it off. We’ve connected with the folks who are growing the native plant starts for next season and have delivered a portion of the seed that they will receive from us. They’ve also begun sowing the seed for next season! Additionally, we visited the restoration site and did some direct sowing of some of our seed collections including, Calamagrostis canadensis, Heracleum maximum, and Angelica lucida. Harvesting, drying, and bagging the seeds brought out a level of satisfaction, but getting them to this stage took many hours of work and was at least a several-weeks-long process for each species. However, seeing the seeds returned to the ground – especially to their final resting place and future site of evolution – was both settling and satisfying for the spirit. I wished them well on their way as I tossed seeds into the black, barren dirt beside Resurrection Creek at the restoration site. “Grow well and help heal this land!” I whispered as they danced their way back into the soil, settling in for winter and, hopefully, reawakening come spring. They’ve had quite the interesting and rare journey over the past few weeks and definitely deserved their time to rest in the wild habitats they’re most accustomed to.