It seemed telling, that the first day I went to check on a lupine population we planned to harvest from, the aspens announced the arrival of fall. It was early August, and thus, to me, unexpected. As I drove up the road towards the lupine patch, I passed the baby swan that we see every time we pass by Tern Lake. The baby has grown a bit larger every time we pass it, marking fast growth in a quickly moving season. When I arrived at the trailhead, I didn’t have to walk very far before I was in the aspen patch where a dense population of Nootka Lupine, the native variety of Lupine on the Kenai Peninsular, resides. I found the pods had turned from a bright green to a deep black. Some had popped open and released their seeds already. Above me the wind rustled the aspen leaves in waves, with the occasional unexpected, deep, swirling breath that signifies the onset of autumn. Suddenly the seeds were ready and fall had arrived, seemingly before the summer had arrived. Time, and thus seed development, happens in a strange and sudden, almost nonlinear, progression here and it’s been keeping us keen and on our toes, ready to harvest on any given day or moment.

The next week we went back to that lupine patch with a couple extra helpers to harvest our first seeds of the season. After weeks of learning, mapping, and monitoring plants, it was surprisingly gratifying to finally pluck the first fruits of our labor and bring them back for processing. In a few hours we had harvested what culminated to about 30,000 lupine seeds. Harvesting seeds from a wild plant makes you notice things about that species and their ecosystem that prior to, you might not. For instance, when lupine pods dry, they spiral. And when they dry out enough, the pop. As we were harvesting the lupine pods, we could hear them popping, spreading their seeds, as they naturally do. Our goal then, was to catch the pods after they had dried but before they had popped, a tall feat in a quickly moving season. Sometimes this window seems to only last a day.

Another thing we noticed about nootka lupine in its natural habitat is that a certain type of small worm thoroughly enjoys its seeds. After popping open a pod, we would often find multiple worms inside of them who had made evident munching holes through several of the seeds. Thankfully there were enough pods and seeds that were worm-free to be very worth continuing to harvest and keep these seeds. Initially, these worms struck me as a bad sign. As one would relate to a food crop being full of worms, they instinctually sent a wave of disgust and dread through my body. But after finding various insects, worms, and spiders in subsequent harvests of different seeds, I began to realize that there was something very natural and right about worms being present in these pods. These seeds were not grown for us, they were not grown for our restoration project, or the ease of our ability to process these seeds for storage and propagation. They were grown for the plants, the place, and the ecology in which they reside. And, though my initial reaction to the presence of these worms was negative, I later realized that bearing witness to interspecies relationships while harvesting a native plant within it’s natural ecosystem was most likely a sign of a healthy and balanced ecosystem. And so although the worms were a bit of a hassle to extract from the seeds while processing them, and while the seed viability of our harvested population decreased slightly because some of them had worm holes through them, my perspective on the presence of worms and insects within the native seeds we were harvesting changed over the last month by normalizing their presence and beginning to question their ecological role and relationship with these native seeds.

Speaking of processing seeds, the above photo illustrates the key tool and method that we have since used to process the native seed that we have harvested. We call it the “Clipper,” and it does a very good job of sorting and winnowing large quantities of native seed. The photo depicts my coworker, Sam, utilizing it to process the lupine seed we gathered. It’s not difficult to use and it greatly increases the efficiency of cleaning seed and sorting out nonviable seed by utilizing a system of different sized screens and fans to filter out the pure seed.

One thing that makes our job interesting is how dynamic it is. Since every native seed that we harvest is drastically different than every other, the harvesting and processing of each seed is unique as well. Thus we must try out the various screens and fan speeds for the clipper with each new species we process. And because this is oftentimes the first time this plant has been harvested for these purposes, we are forced to get creative and figure out the best way to do both process, as well as harvest these seeds.

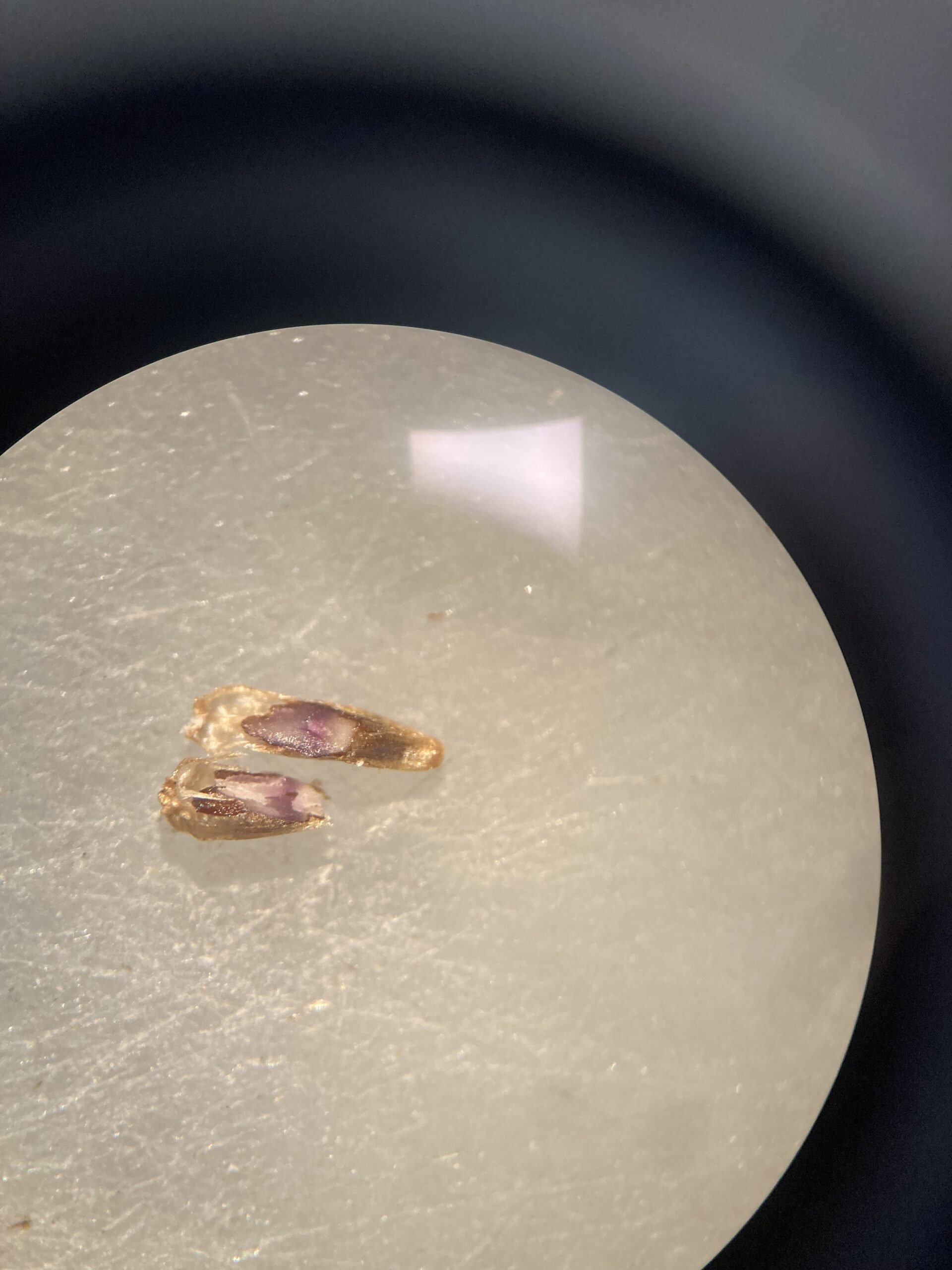

The inherent diversity of these seeds also means a lot of variability in the signs of readiness of mature seeds between different species. In order to check seed readiness, we perform cut tests under a microscope, to get a clear vision of the structure and state of the inner tissues of the seed. Seeds tend to solidify as they mature, but the exact consistency of the megagametophyte (inner tissue of the seed within the seed coat upon which an embryo feeds) of a mature and ready-to-harvest seed seems to vary between plants. The inner tissue of the lupine seeds were very hard, even to the extent that they were difficult to cut through, whereas the megagametophyte of Carex mertensii (Merten’s Sedge) is much softer than the lupine, though still seemingly mature.

My own discernment of a mature seed from an immature seed is still developing, though I have noticed that it is getting better and better the more seeds at the more stages I observe. For example, we are currently monitoring the seeds of Swamp Cinquefoil (Comarum palustre), for which there is no information available online about how to discern a mature from an immature seed. While the seed is still a bit soft on the inside, after watching the progression and gauging the thickness of the seed coat, we think it is just about ready to harvest. It is important to note that the discernment about the development of a seed in relation to when to harvest it must also be balanced with observing when and how quickly the plant is dispelling the seed from the fruiting body. Oftentimes we have waited because the seed doesn’t seem quite solid and thus developed enough to harvest. But then, the next time we go back to check it, the seed has been expelled as the plant intended, lost (to us) within the soil seed bank, exactly where it wants to be.

While this is a challenge to correctly time, especially when juggling multiple species, all with different schedules (as well as different schedules for the same species in different locations and microclimates), this has been a gratifying skill to hone. It is both science and art. I often find myself and my field partner consciously or unconsciously calling upon our intuition to decide where we need to go on a given day. It’s happened on multiple occasions where we have made a plan of where to go the day before, but when we get to the office something is calling one of us somewhere else. Thankfully we are both generally flexible and often trust the other if they are getting a calling to a particular place on a particular day. More times than once, we have trusted that calling and have both been pleasantly surprised that a certain plant or seed we weren’t even thinking about was ready and needed to be harvested that very day. So that is another aspect of the job that I am enjoying – that it is both a science and an art, and that the more artistic and intuitional aspects of it strengthens and reinforces the depth of connection and integration one has with the ecosystem they are working within, encouraging one to be more in-tune with the land they are working with.

Anyways, since a picture can say a thousand words, I will finish this blog post by sharing many of the photos that I have captured within the last month while out monitoring and harvesting seeds, pairing them with descriptions to give a little bit of an insight into our day to day activities while harvesting native seeds for restoration out in the Chugach National Forest.

The Land We Work Within

Berries Found While Working

The Plants We Work With or Alongside

Seed Harvesting and Processing Procedures

Alaskan Autumn Aesthetics

Now we’ve got to get back to harvesting, for it is high season and by the next blog post I presume none will be left. Stay tuned.