Headed northbound on I-55, I found myself surrounded by fields of familiar Illinois flora: Zea mays and Glycine max, better-known by their common names “corn” and “soybeans.”

Upon my return home from college, however, I now also eyed scattered blooms of Spring Beauty (Claytonia virginica), Wild Hyacinth (Camassia scilloides), and Shooting Stars (Dodecatheon meadia) in preparation for the next six months spent at Midewin National Tallgrass Prairie.

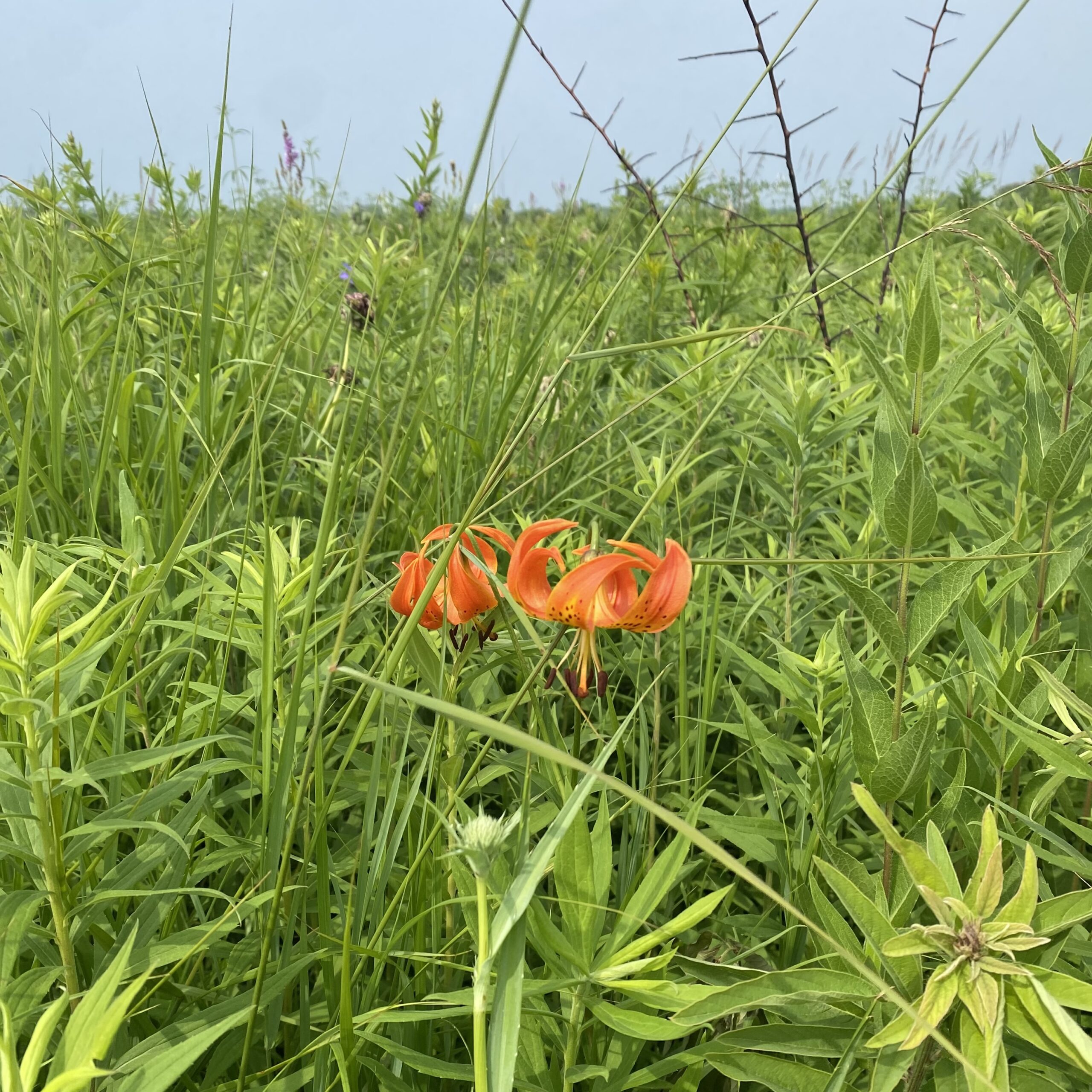

Formed by glacial outburst floods during the Ice Age, Midewin and the surrounding areas host some of Illinois’ last remaining dolomite prairies. Numerous rare plant species call this habitat home, spared from the plow due to its characteristically thin soils.

This unique plant community has presented the opportunity to work alongside the Chicago Botanic Garden’s Plant of Concern program, monitoring sub-populations of Small White Lady’s Slipper (Cypripedium candidum), Slender Sandwort (Minuartia patula), Butler’s Quillwort (Isoëtes butleri), and Buffalo Clover (Trifolium reflexum).

Many weeks have already been spent stumbling through sedge-meadows and honing my plant identification skills — much needed for the intimidating amount of Carex on our Target Species List.

Other days have been used to put my CLM training to the test, collecting seed from Yellow Stargrass (Hypoxis hirsuta), Blue-Eyed Grass (Sisyrinchium albidum), and Prairie Violet (Viola pedatifida) from a patch of remnant prairie at Lobelia Meadows.

Despite being raised less than 10 miles away from Midewin National Tallgrass Prairie, I’ve already explored it more this past month than I have my entire life.

And although it’s no Chugach or Tongass National Forest, Midewin is nevertheless a gem of the Prairie State — no matter how many acres of corn and soybeans hide it.

Dade Bradley

Midewin National Tallgrass Prairie