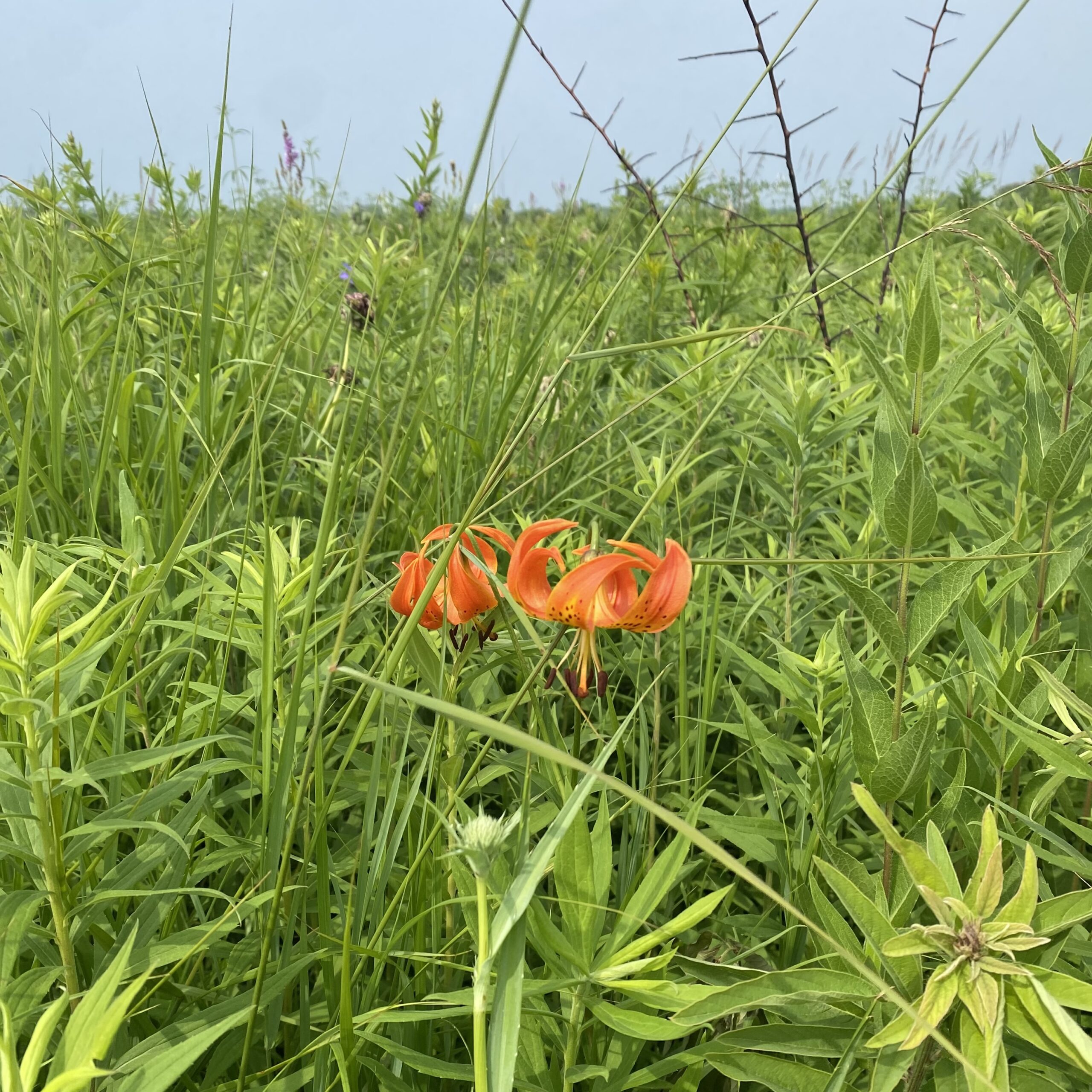

Once spanning over 170 million acres of the continent, Illinois was one state among many that hosted tallgrass prairie. Within this greater ecosystem was a mosaic of smaller habitats ranging from dolomitic pavements, sand hills, and wetlands.

Its rapid destruction by drain tile and plow, however, has made it one of the most endangered ecosystems in North America. In less than two generations, over 95% of the tallgrass prairie was destroyed and replaced primarily by commercial agriculture.

There are just twenty designated National Grasslands in the United States — all located west of the Mississippi River. Just 60 miles south of Chicago, however, Midewin is the country’s first and only “National Tallgrass Prairie.” Other nearby natural areas, like The Nature Conservancy’s Indian Boundary Prairies, are located even closer to city limits.

During a visit to Paintbrush Prairie Nature Preserve, the site manager & entomologist explained how many insects and plants alike may be classified as “remnant-dependent.” And with less than 4% of remnant tallgrass prairie remaining, these sensitive species are at risk for extinction.

Days not spent collecting seed were often used to monitor rare species with the Chicago Botanic Garden’s Plants of Concern program, such as the state-endangered Buffalo Clover (Trifolium reflexum).This species thrives on disturbed sites, and is believed to have gotten its name from its tendency to grow in buffalo wallows.

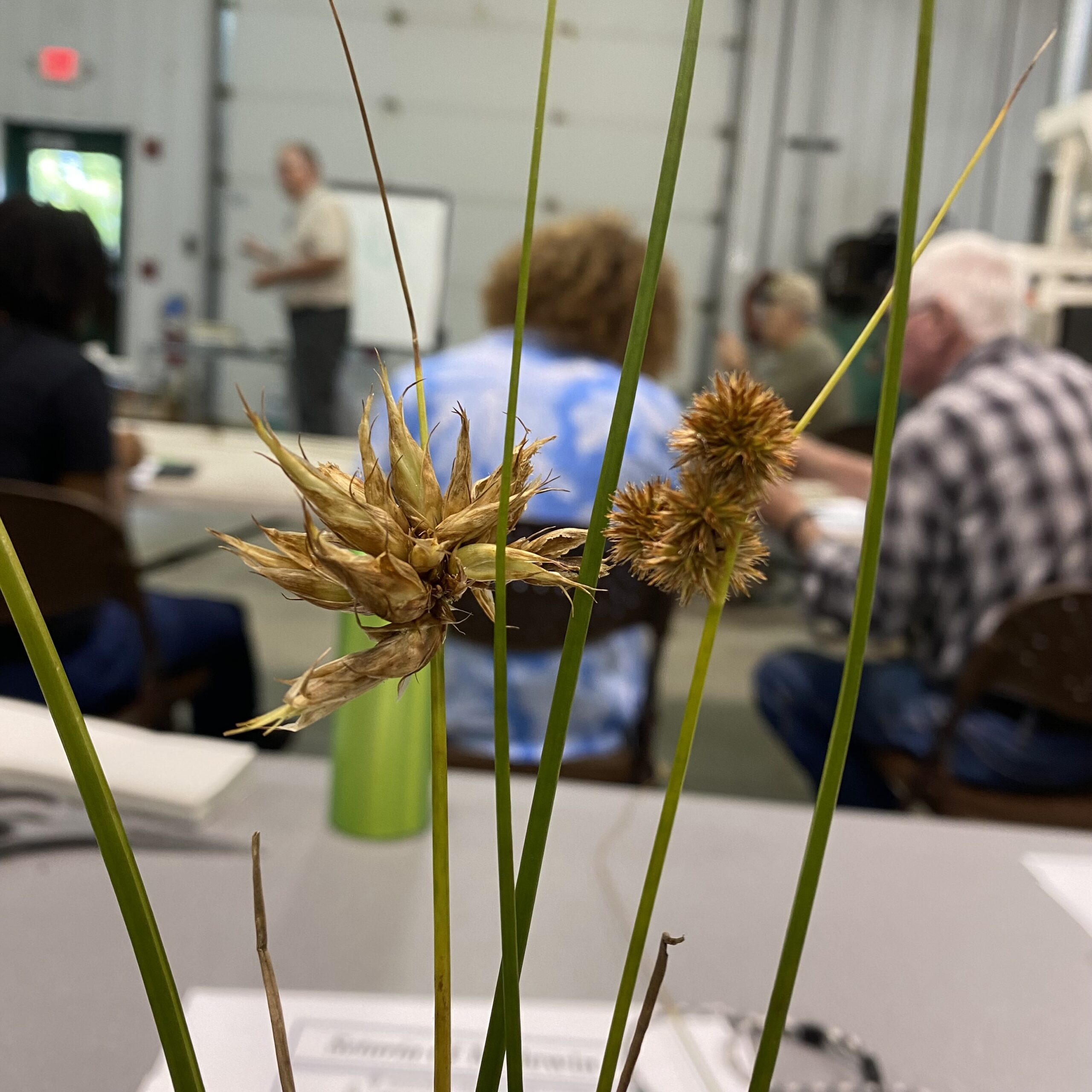

Field days always presented new opportunities, such as accompanying the Wildlife & Range crews for robel pole monitoring and cover board surveys; or floristic quality inventory assessments and meander surveys with the Botany team. And because all seed is processed in-house at Midewin, we also got hands-on experience in native plant horticulture.

My summer spent as a Conservation and Land Management intern was the perfect chance to explore an early career in botany, right in my own backyard.

And although I wasn’t camping in Californian deserts or collecting high-altitude plant species in the Rocky Mountains, Midewin’s unique locale offered relevant experience for an aspiring land manager.

Dade Bradley

Midewin National Tallgrass Prairie