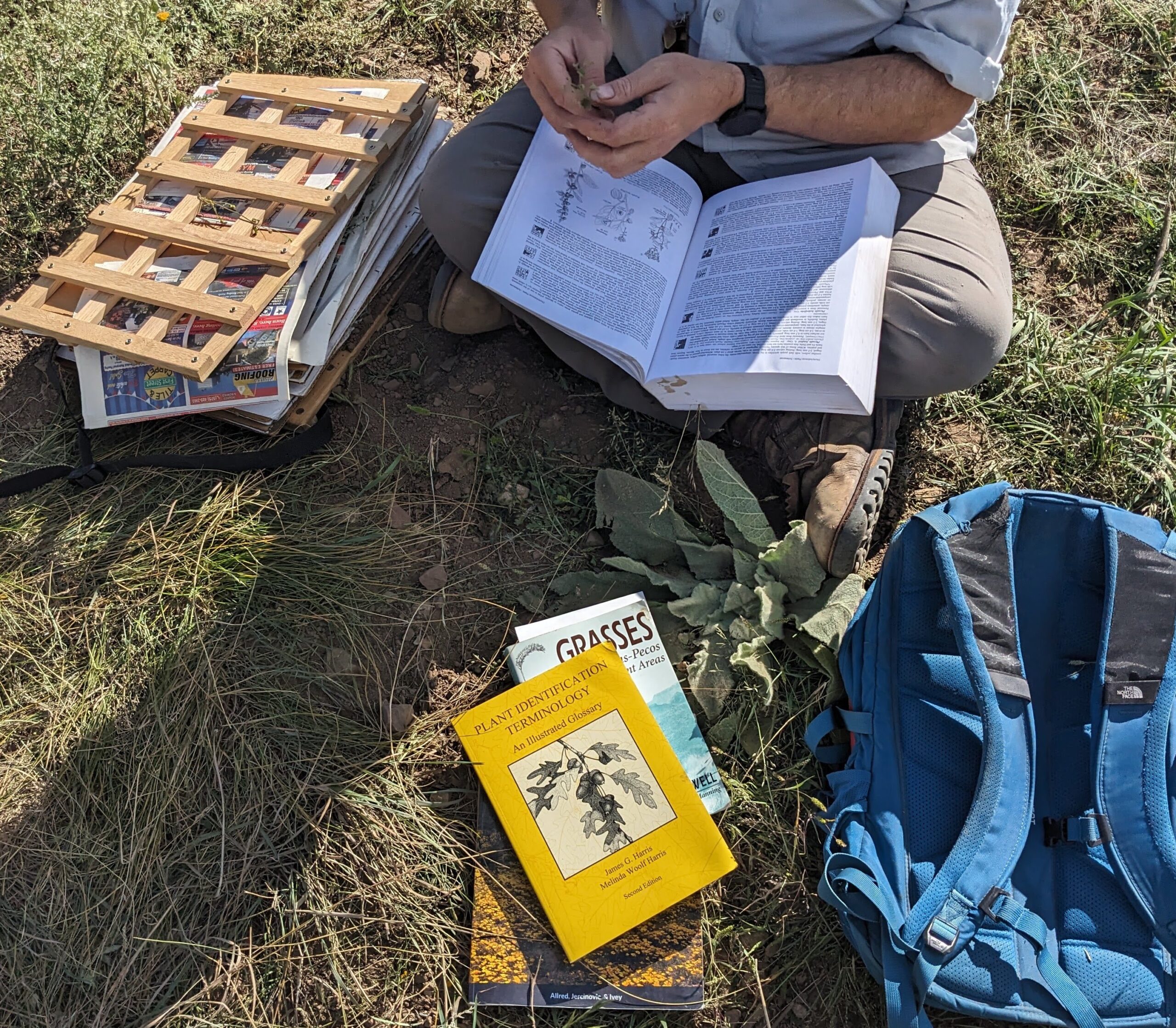

I had an unexpected end to my season in the Lincoln National Forest. The looming government shutdown had me holding my breath, wondering how I would spend my last month. On top of that, Evie had been called for jury duty and was planning on leaving early. In a turn of events, both were avoided. We finished this month strong with seed collecting and grazing allotment vegetation surveys. During our “off” days, we helped Range with allotment surveys. We followed the “Common Non-Forested Vegetation Sampling Protocol” (CNVSP), which collects data on vegetation composition, species richness/abundance, ground cover conditions, and dry-weight composition. I’m glad we were able to help out with these surveys, as they flexed our growing botanist muscles. Every plant in the survey needs to be keyed out, meaning no plant gets left behind. It’s tough keying plants because of how dry everything is. Not many species have fruits or foliage left (if they had any to begin with).

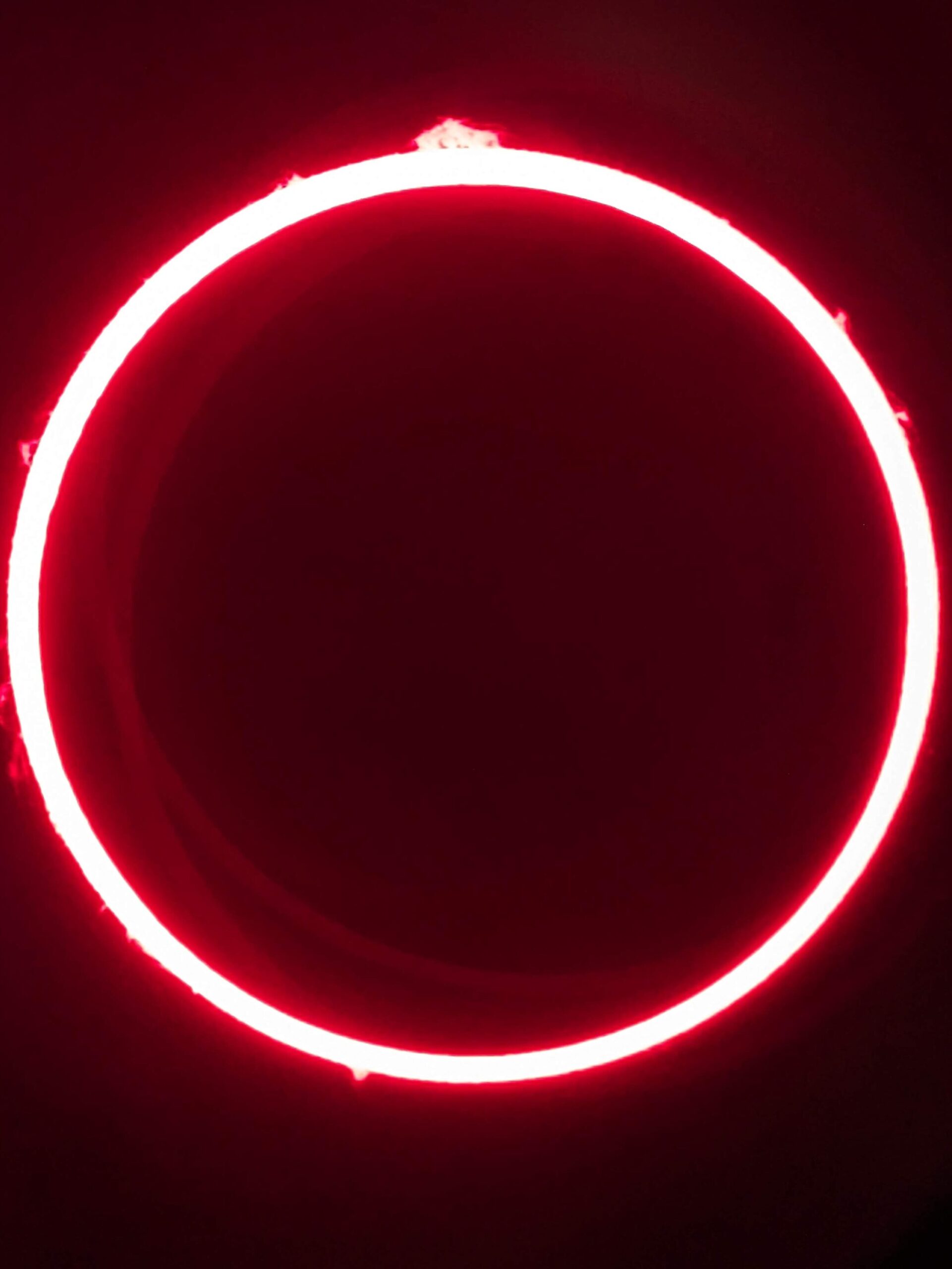

The forest has been ablaze this month (in color, not flames). The aspens, insects, and sun have taken the edge off the evening chill with their fiery displays. I’m used to fall in Ohio, where you’d be lucky to have a single day without a cloud in the sky. Here in New Mexico, that’s a common occurrence. The annular eclipse, however, was not. On the morning of Saturday, October 14th, the moon waltzed in front of the sun. I met up with Evie and Spencer (a Natural Resources technician with the Forest Service) at Bitter Lakes National Wildlife Refuge, northeast of Roswell. The path of totality fell directly on Bitter Lakes, meaning we could see the infamous “ring of fire.”

We patiently waited for the first sliver of celestial shadow to appear in the upper right corner of the sun. An astronomy hobbyist graciously let us borrow his hydrogen telescope for a better look. Not only could we see the moon’s outline, but also sunspots and solar prominences. As the eclipse progressed towards totality, the Refuge started to hum with excitement from fellow eclipse watchers. Yet, the air had its warmth steadily drained as the solar energy was blocked by the moon. It was the same temperature–if not cooler–as when we had arrived at 8 a.m. Time sped up and slowed down. Shadows behaved strangely, masquerading as miniature displays of the eclipse overhead. Because it was an annular eclipse, the sun was never entirely blocked by the moon. Plenty of light made its way around the moon’s edges, making it unsafe to look at without eye protection. Totality lasted 4 minutes but felt much shorter. The eclipse wasn’t inherently spectacular to a layperson, but the shared experience of such a unique moment made it memorable.

This season was filled with other memorable moments, from seeing my first Mexican spotted owl or looking for Sacramento Mountain salamanders to nearly getting hypothermia while participating in a Hawkwatch survey (everyone underestimated how cold it would be). I’m grateful for the wonderful memories, lessons learned, and friends I’ve made along the way.

I may be leaving Lincoln National Forest and Ruidoso, but my time in New Mexico is not done! I will be working in Carlsbad, NM, as a Botany Support Specialist (through Conservation Corps New Mexico) with the Bureau of Land Management immediately following this position. There, I hope to use what I learned about seed collecting and the flora of New Mexico to assist other Seeds of Success (SOS), Assessment, Inventory, and Monitoring (AIM), and Special Status Plant Species (SSPS) crews with their work.