Again and again, I was told “Don’t go to Bakersfield.” It’s hot, hotter than the desert, where a stagnant wind whips the dust into a meringue that sits in the air for days at a time. This is oil country, with many acres dedicated to extraction, for instance in McKitrick, where you can actually see the “bubbling crude” pour out of, and merge with, the ground. My mentor, Denis, tentatively admitted: “getting around in Bakersfield may be difficult without a car.” We will occasionally be working with dust masks. There is a cool local disease called “San Joaquin valley fever” caused by a fungus in the soil that gets kicked into the air during sporadic rainfall.

Since I am a contrarian to the core, and a “different kind of drummer” (says Rachel,) I wanted to see just what made this place so difficult. Have you ever had that carrot juice? The expensive one on sale at Safeway? That’s made by Bolthouse Farms, located here in the southern San Joaquin valley. The valley, which receives relatively little precipitation, grows 3% of America’s produce and extracts a little less than 1% of the world’s oil, which is a lot. So the urban explosion of Southern California is synonymous with water scarcity.

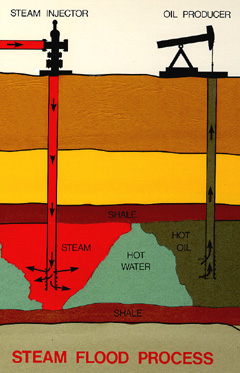

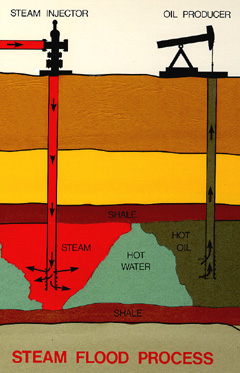

from SJV geology: steam drilling

It is easy to fall into the trap of forgetfulness, to forget that everything is connected with everything else. How could drinking a carton of carrot juice impact a population of burrowing owls or the kind of water that flows through the taps of the Buck Owens Crystal Palace? If you’re coming this way, come to Bakersfield. I want you to see, breathe, smell it and feel it for yourself. I want to take you to the orange groves. We made this place difficult to live in, and a life of ease is a life of ignorance.

One of the BLM’s great projects out here is an attempt at restoring wetlands near the original site of Tulare, the largest freshwater lake west of the Mississippi. The fight still rages for every last drop of water, and our acquisition of Atwell Island is, when put into perspective, quite impressive.

Wait, what lake?

This lake. (source: Delta national Park.org)

Tulare Lake used to capture all of the meltwater from the Sierra mountains, an important stop for waterbirds on their inland migration. Today it looks quite different, as nearly all of that mountain snow gets intercepted by the farmers who live upstream. On the site itself, the soil has become too alkaline, too enriched with selenium and salt, to prove profitable. Gradually, farmers are selling their unprofitable cropland to the BLM, where a massive wetland restoration is taking place. So far, Atwell Island consists of land and water along an old sandbar. You wouldn’t believe what you’ll see if you head to Atwell Island or to the national wildlife refuge nearby. Birds sighted on a count in 2007 included

“…sandhill cranes, barn and horned owls, kites and harriers galore, red tails a-courting, several sparrows, marsh wrens, black phoebes, redwing and Brewer’s blackbirds, shrikes, whimbrels, long-billed curlews, killdeer, black bellied plovers, avocets, stilts, cinnamon, green-winged and blue-winged teal, mallards, ruddy ducks with bright cheeks, cormorants and ring-billed gulls. Several sightings were records for the project.”

Although recovery for birds seems dire in a salt-drenched and blazing hot landscape like this, there’s a glimmer of hope for wildlife. Somehow the birds keep finding their way back. We are actively introducing them as well; one of our first activities as a team was the release of four burrowing owls from L.A into artificial dens originally intended for another nocturnal predator, the San Joaquin Kit Fox. You can watch a video of my mentor, Denis, releasing a burrowing owl here.

https://picasaweb.google.com/100594521801634340032/AtwellIslandBurrowingOwlRelocation?feat=email#5727351485441522850

The Carrizo Plain, one of our most visited sites, is turning many pretty shades of brown right now as everything dries out.

The Carrizo Plain, one of our most visited sites, is turning many pretty shades of brown right now as everything dries out.