2019 has been a whirlwind. From wrangling hiring paperwork during a government shutdown to carefully doling out ice water from the thermos in 104° heat, there were trials and tribulations the entire way. This past year, I’ve bounced between four different funding sources, but my primary focus has been the Rare Plant Monitoring Program out of the BLM – New Mexico State Office. This program works hard to develop datasets and protect species before they get federally listed. This crew, based out of Santa Fe, monitors species in every field office of New Mexico. We spent so much time on the road that we listened to the entire Lord of the Rings trilogy on Audible before mid-season reviews!

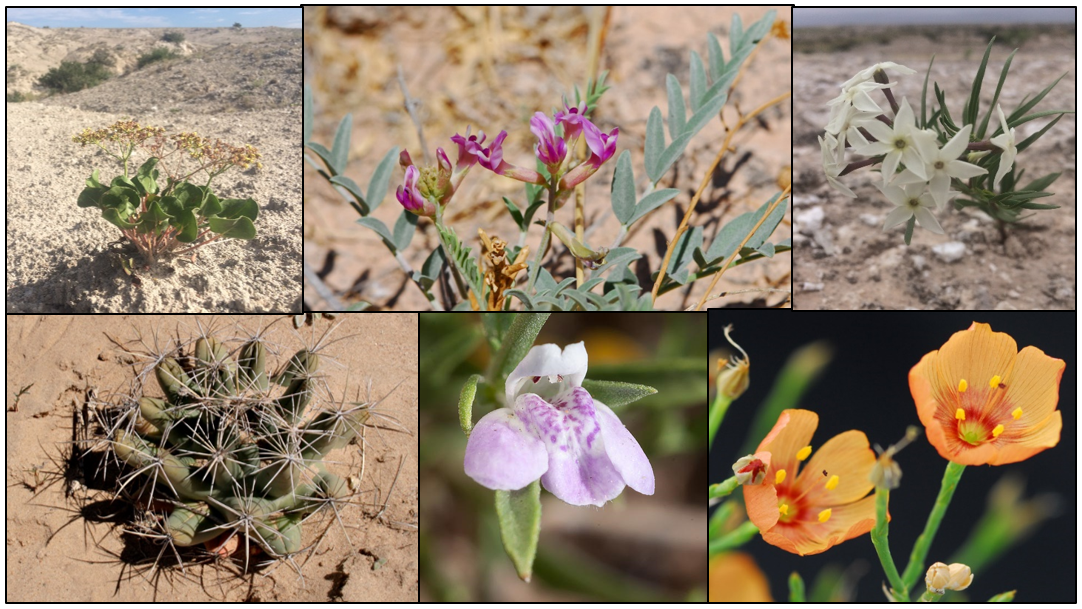

We read 70 previously established plots and constructed an additional 29 new plots. These permanent transects are used to collect baseline demographic data for these species: what is recruitment like? What is mortality and lifespan for an individual? What reproductive effort is being made by individuals? By collecting this type of data over five or ten years on rare plant species that occur mostly on BLM land, the Botany Program can better inform management practices to protect these species. 2019 was the fourth year of this program, and a lot of species are still being added and kinks are being worked out. This made for an interesting season in which every week we were facing new challenges. Throughout this season, I developed rigorous monitoring methods, improved my plant ID skills, and dove into the wonderful world of geospatial data. It’s deeply rewarding to know that these species that I got to know so intimately have a brighter future because of our work.

Since reading our last plots in November, we’ve been working on reporting and analysis for the plots we’ve read. This has been a wonderful opportunity for me to relearn R. Though I love to hate R, it’s a crucial skill for graduate programs and employment, and has made for really robust reporting in the Rare Plant Monitoring program. My crew lead, Lauren Bansbach (featured triumphantly holding an Agave above) is staying on for another season with the Rare Plant Monitoring program. I can’t help but feel jealous and sad that it’s over so soon.

Mike Beitner

Bureau of Land Management

New Mexico State Office