The Conservation and Land Management internship with the US Fish and Wildlife Service – Klamath Falls Field Office continues to keep us interns busy by providing us with numerous opportunities to go out and do various types of fieldwork. We have also had a few office days this past month or so, in which office work usually consists of doing research via searching for/reading articles and writing annotated bibliographies to help our supervisor, the fisheries biologist, with his task of writing biological opinions. On days that we aren’t working on projects out in the field or days when we are not assigned research to do for office work, we usually find stuff to do to keep us busy for the day. This usually involves updating our resumes, looking up jobs, or working on writing another blog post for the internship. This past month or so, the projects that we have gotten to help with consisted of duck banding at Summer Lake, more electrofishing within Long Creek in Bull Trout critical habitat to remove Brook Trout, and telemetry.

The task of duck banding at Summer Lake was unique, action-packed, and exhausting. The project was led by the Klamath Basin National Wildlife Refuge Complex staff, while the other intern and I, along with some staff from the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, assisted in banding the ducks.

The duck banding project, which took place at night over the course of a few days, involved driving airboats around within the wetlands throughout the refuge. The process consisted of the airboat conductor driving by flocks of ducks and spotlighting them while they were sitting on top of the water. Once close enough to the ducks, the other individuals in the boat utilized nets to capture the ducks and then put them in large holding crates on the airboat. At times, it was tough capturing the ducks, as most can fly, in which some ducks would simply fly away before we had the chance to get to them. Also, we had a few that flew out of our nets before we had the chance to handle them and put them in the crates. The airboat was also utilized to chase down ducks that were trying to move away from the boat by swimming/running on top of the water. If this was the case, the netters would have to try and net the ducks while the boat was in acceleration. This was quite difficult, making it tough to net birds on the move, as we had to act quickly and try and net the duck within a split second, or else we would miss the duck as the boat passed by, causing us to have to turn the boat around to try and catch the duck that was missed. Each time the boat had filled 4 crates worth of ducks, the boat returned to shore where the banding station was set up. After the crates were unloaded, the ducks in each crate were organized by species, age (i.e., local, hatch-year, mature), and sex to make the banding process and data collection more efficient and quicker. Keeping the ducks at the banding station organized ensured that the ducks offloaded from one boat had been banded and processed before the next boat arrived with more crates of ducks.

After the ducks were processed and had received a leg band, they were released unharmed back into the wetlands. The species of ducks that were banded included Gadwall, Mallard, Pintail, Bufflehead, and Green-winged Teal.

To cap off the last night of duck banding, I was offered the opportunity to gain experience driving the airboat, in which I got to drive it around the wetland a bit and then load the boat onto the trailer. Operating the airboat was fairly simple, as there is just an accelerator and a steering lever utilized to maneuver the boat.

After 3 days-worth of banding a total of roughly 2,000 ducks, in addition to staying in refuge housing for the duration of the banding project, I was exhausted and ready to come home, although, I really enjoyed having the opportunity in gaining duck banding experience.

The task of removing Brook Trout in Bull Trout critical habitat via electrofishing within Long Creek was one of the more exciting projects we have gotten to do during the internship so far. The purpose of removing Brook Trout from the creek was due to Brook Trout being an introduced fish species in Oregon, which their population has increased dramatically in many watersheds throughout Oregon since their introduction, causing native species of fish, including Bull Trout, to become displaced from their native ranges. The process consisted of electrofishing while moving throughout the stream, trying to catch and remove as much Brook Trout as possible. There was never a dull moment of electrofishing as we walked through the stream, as there were a ton of Brook Trout inhabiting the area of the stream we sampled. Over the course of 2 days of electrofishing, we had caught and effectively removed a total of 560 Brook Trout from Long Creek.

Mostly all the fish that were caught had been fairly small, although we caught a few larger fish that were inhabiting parts of the stream, in which the largest Brook Trout we had caught measured 9.75 inches in length.

The larger Brook Trout that were caught were kept with us in a fishing pouch as we worked our way through the stream. At the end of the day, we used a PIT Tag reader on the larger fish to see if any had possessed a PIT tag, but none had contained a tag. In addition to catching Brook Trout, we had also caught a few Rainbow Trout while electrofishing which we had released back into the stream unharmed.

One of the most recent projects that the USFWS Klamath Falls Field Office offered us interns consisted of obtaining telemetry experience. The process consisted of going out and using telemetry equipment to try and estimate the general location of a mammal radio collar that had been randomly placed within public forest land by one of the wildlife biologists.

The components of our telemetry setup consisted of a radio receiver that received signals from the radio collar, along with 2 antennas, 1 that was affixed to the top of our vehicle to monitor the radio signal of the collar while we were driving around on backroads throughout the forest, in addition to a handheld antenna that was used for surveying in spots where the car antenna had picked up a signal from the radio collar.

The use of the handheld antenna was beneficial as it allowed us to get a sense of the general direction of the radio collar. We surveyed areas within public forest land in search of the collar while conducting the triangulation method with the telemetry equipment. The triangulation method consisted of going to multiple locations and using the telemetry equipment to determine the direction in which the strongest signal is received from the radio collar. When we found an initial spot to survey, we ensured that the gain was set to a high value to increase the sensitivity of the receiver. At a high gain, we were able to detect a signal from the radio collar and get a general sense of the location of the collar from the initial survey spot by doing a complete 360-degree circle with the telemetry antenna and listening to the signal strength on the receiver. Once an initial signal was received and the signal direction was documented of the estimated location of the collar, we decreased the gain setting on the receiver, making the receiver less sensitive to the radio collar signal. We lowered the gain until we could barely hear the beeping sound of the signal in the direction of the estimated location of the collar. After having found a gain setting to start tracking while at our initial survey spot, we drove around and listened for a signal detection via the car antenna.

For a given area where a signal was detected by the car antenna, we got out of the vehicle and surveyed the area using the handheld antenna, and estimated the general direction where we heard the strongest signal from the collar. At each spot surveyed, while the gain on the receiver was kept the same, we determined if the beeping sound (i.e., radio signal) was getting louder or quieter than the initial survey spot. A stronger signal from the radio collar that was picked up by the receiver (i.e., meaning the collar was in proximity), was illustrated by a louder, more definitive beeping sound on the receiver. Alternatively, if we were receiving a weaker signal from the collar, illustrated by a softer beeping sound on the receiver, it meant we were farther away from the collar. In areas where we noticed the signal strength was increasing and the receiver was illustrating relatively high values of signal strength, meaning we were getting closer to the collar, we had to decrease the gain setting (i.e., sensitivity) on the receiver. If the gain setting were to be left at a higher value while the signal became stronger once in proximity of the collar, it would make it difficult to discern the directionality of the signal due to the higher sensitivity causing the signal to become static, making it harder to hear the beeping sounds on the receiver. Some aspects of telemetry that made tracking tough and stressful at times involved the presence of topography within the study area. Hillsides, peaks, valleys, trees, etc. can potentially disrupt the radio signal, causing confusion about the directionality of the signal from the collar. For example, at times, there was the potential of “signal bounce” occurring when we were surveying and pointing the handheld telemetry antenna in the direction of a hillside/mountain.

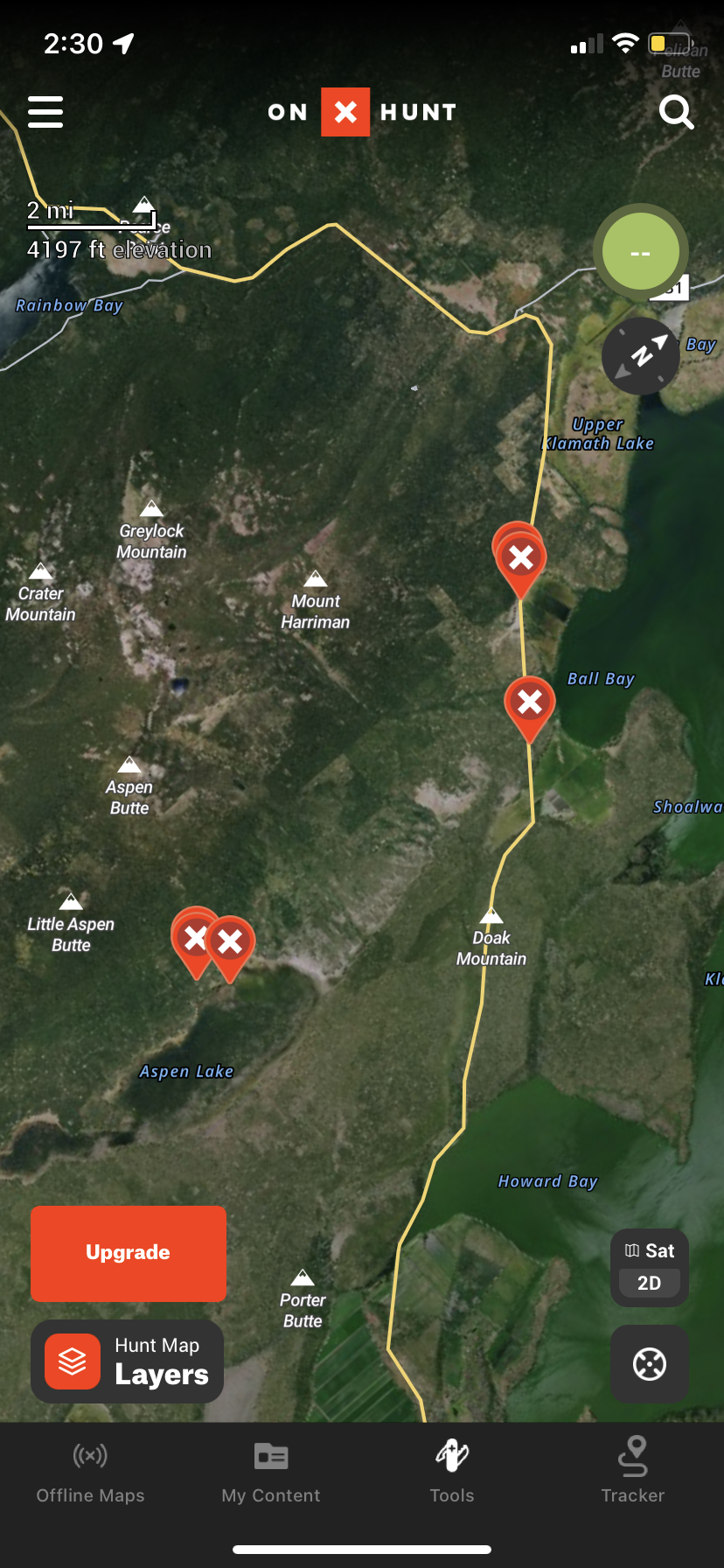

The term “signal bounce” means that there is a possibility of receiving a signal in the complete opposite direction of the radio collar due to hillsides/mountains in the area influencing the radio signal. Additionally, vegetation, such as trees, can disrupt the radio signal as well. In areas with densely populated stands of trees, we may not hear any signal, whereas if we walk 50 feet down the road away from the trees, we may pick up a signal of the collar. Because of the aspect of “signal bounce”, as well as vegetative growth in the area, we had to always consider our positioning/location in relation to landmarks and vegetation when we were tracking the radio collar to determine the most accurate directionality of the radio signal. Throughout the tracking process, we used an app called onX that allowed us to set waypoints on a digital map at locations we surveyed and had received a signal from the collar.

Plotting more than a few waypoints on the onX map helped us better determine the general area where the radio collar might be due to us being able to keep track of each spot we surveyed where we heard a signal from the radio collar. If we weren’t utilizing the digital onX map and did the triangulation method on paper while using a modern map to keep track of the areas where we had heard a signal, after figuring out where the surveyed locations (i.e., points) intersect with each other on paper based off the signal direction of each, the area within the intersection of the surveyed points on a modern map would signify the estimated location of the collar. Before the telemetry project, I had not had extensive experience working with telemetry, other than participating in a telemetry workshop while attending college, in which the workshop leads taught the participants how to properly use the equipment. By being able to work with the telemetry equipment these past couple of days while trying to get an estimated location of a mammal radio collar, I have learned quite a bit more about telemetry.

In conclusion, the past 4 months of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service internship in Klamath Falls, Oregon have been nothing short of fascinating, as the various projects we have gotten to assist with have kept the job interesting and exciting. In addition, it is awesome that there are quite a few recreational opportunities within an hour’s drive of town, such as fishing, hiking, and surfing/boogie boarding. This past month, I have finally ventured out to the Oregon coast and did some boogie boarding and surfing, in addition to finding a few fishing spots along the way.

It was really exciting getting the opportunity to try surfing for the first time via taking surfing lessons with a local surf shop. One of the things that I have wanted to try for quite some time that I haven’t been able to do coming from the desert of New Mexico was surfing, in which I had a blast learning how to surf. The past few weekends, I have made it back to the coast to do more surfing, and it has been a lot of fun trying out different boards that vary in length to experience how each board reacts when riding a wave.

Overall, I have really enjoyed my time in Oregon, and I have recently applied to other fisheries jobs that are along the Oregon coast in order to have additional time to surf, as well as have more opportunities to explore the numerous hiking trails, lakes, and rivers that Oregon has to offer.