…back to Chicago and leave the “Red or green?” chile state that has become my home for the past five months, I want to take this opportunity to reflect and reminisce on my time spent here.

A Rocky Start to the Season

At the beginning of the season, my co-intern and I encountered some difficulties that hindered our ability to start scouting for species in our target species list. The first problem that we encountered was that there were no established protocols to do scouting and seed collection as it was the first time Lincoln National Forest had any CLM interns. Thus, we did not know how we were going to collect data on our scouted populations. Second, our target species list included over 200 species, so we were unclear about which species we should prioritize and whether we would be capable of making at least 8 collections with 30,000 seeds due to the climate and condition of the forest with smaller populations.

One might have been worried about the situation, but I was not. I knew with the help of our mentors we would eventually figure it out and we did. After meeting with the Southwestern Regional Botanist, the Institute for Applied Ecology, and the Chicago Botanic Garden, our goals were made clear with our target species list, our seed collection goal, and the protocol and applications we will be using.

Not long after, we were on our way to officially start scouting.

A “Bleak” Monsoon Season

New Mexico is one of the states in the United States that experience monsoons. Between the months of June and September, the state experiences more rain. Our mentors said we would be seeing an abundance of plants once the monsoons hit, so my co-intern and I were looking forward to adding new scouting points and collecting seeds. However, this summer, it was more of a “nonsoon” season as it didn’t start until late July and many parts of New Mexico experienced below-average rainfall. Thus, the number of new wildflowers and potential seed collections that we expected to see was no longer a reality.

Helping with Forest Service Projects

Besides scouting and collecting seeds, we helped the Forest Service staff with several projects. Some required our botany expertise while others required physical labor.

Projects we helped with include:

- Goodding’s onion survey and seed collecting

- Sacramento Mountain prickly poppy survey

- New Mexico meadow jumping mouse monitoring

- Sacramento Mountain checkerspot butterfly monitoring

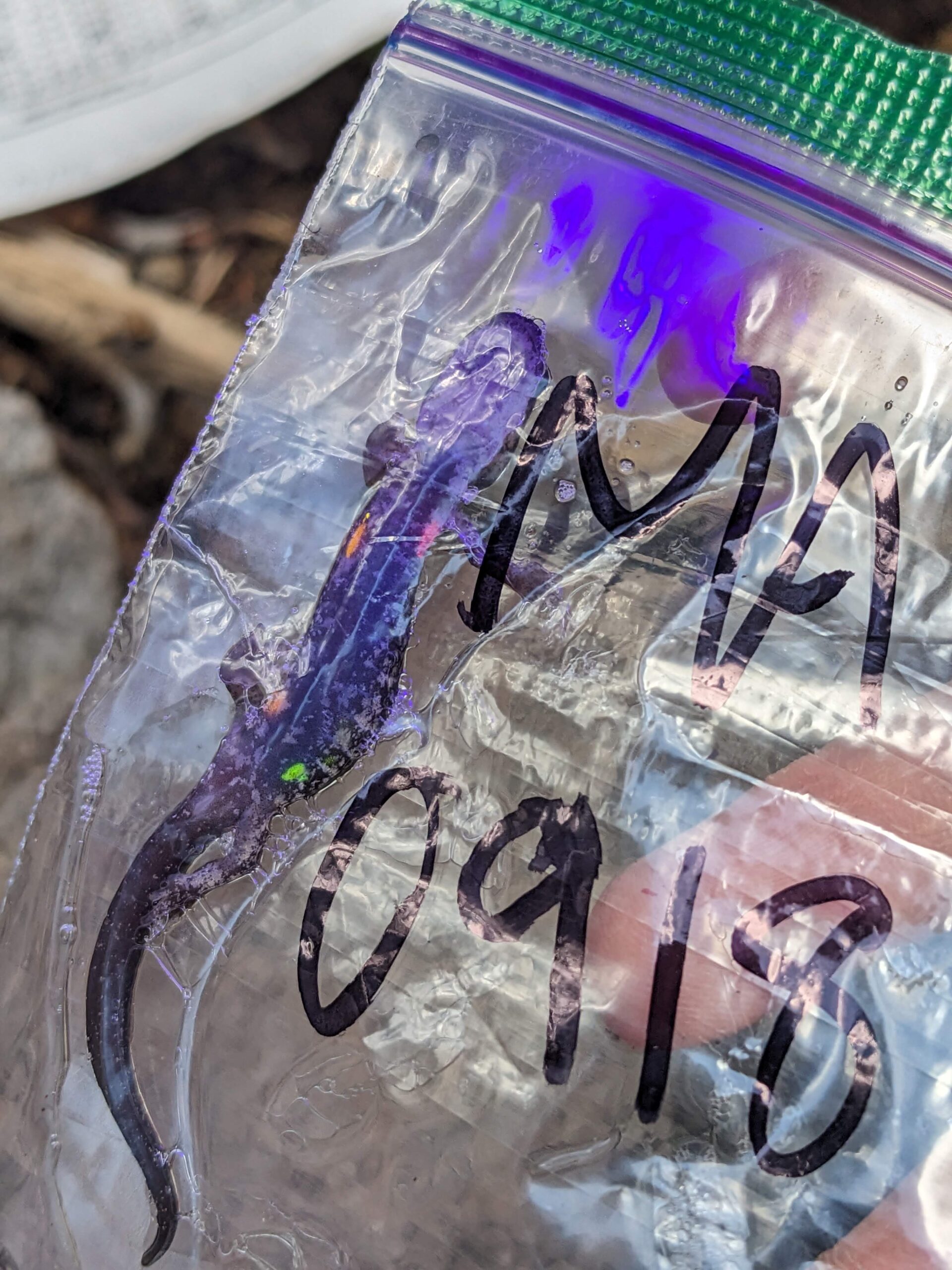

- Sacramento Mountain salamander survey

- Smokey’s Garden planting

- Big Bear Canyon riparian restoration

- Sacramento Mountain checkerspot butterfly habitat restoration

- Grazing allotments monitoring

Overall, it was fun not only learning new skills but also meeting and working with a diverse group of people for these projects. The most rewarding part is hearing about their experience and how they got working with the Forest Service.

Exploring the Unknown

The best part of living in a new state is the chance to explore it. Although I did explore a good part of New Mexico, there are still towns, National Forest, and National Monuments that I did not get a chance to explore. Nonetheless, I still had fun exploring.

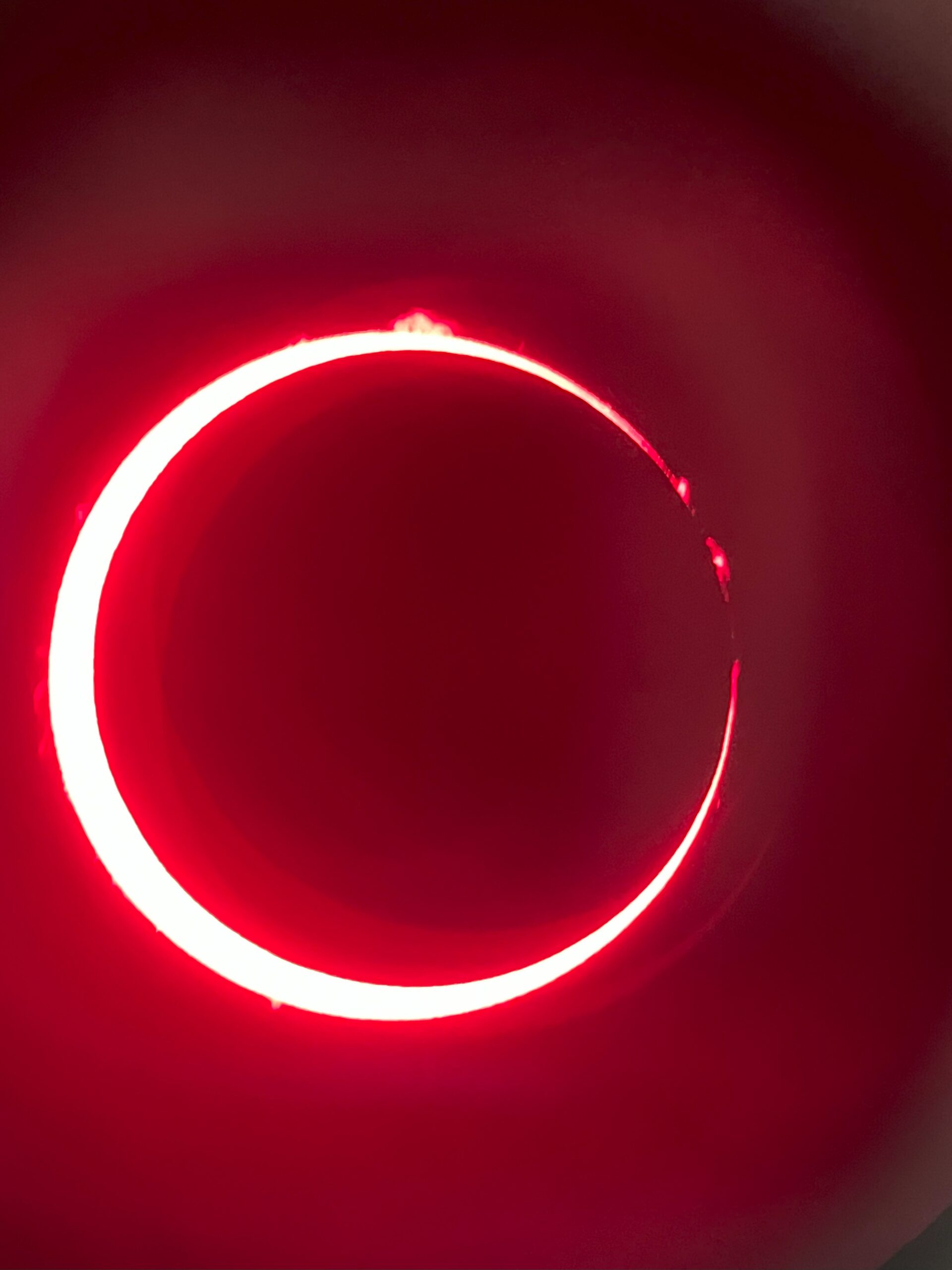

Here are some of my favorite events and places I got to experience:

Exploring is not only about visiting places but also about the food. If you are ever near Ruidoso, I highly recommend Oso Grill and Club Gas. Oso Grill is known for their award-winning green chile cheeseburger, and nothing compares to Thursday night enchiladas dinners at Club Gas.

Overall, I am grateful for being part of the CLM program this season.

– Evie