September 28th, Saturday

A buzz in my earpiece plucks my attention away from the bride, gliding down the aisle toward her groom to the tune of “Bloom” by the Paper Kites. What is it now? I whisper in annoyance. Not now! I pick up the call and the news drops. Fire on the mountain. “They’re calling it the Elk Fire, up near Dayton, Riley Point”. It’s Kaitlyn, my co-intern, measured in her tone, but voice barely concealing a smoldering anger. I grit my teeth as the soon-to-be-wed couple meets at the altar, and the ceremony begins. “How?” I hiss into the earpiece. “Lightning strike”, Kaitlyn growls. The blasted cumulonimbi! Confound them! Lurking all summer, teasing with strikes every hot, muggy afternoon, just now making their move right as all our backs are turned… An electric rage crackles across my skin, and I hear roaring thunder at my temples as my head pounds. Not on my forest!

“If anyone objects to the wedding of this couple, speak now or forever hold your peace!” calls out the priest at the altar.

“Hold it!” I leap out of my pew, and the crowd gasps. Striding up the aisle towards the ceremony, I say, “Congratulations, but I’ve got to go.” I reach out to shake the hand of my cousin, the groom, as he furiously gestures for me to take a seat. I turn to address the family and friends— “The plants. Botham City. They need me!” I hear the bride mutter behind me, “um… who is he?” I turn my head halfway to face her, and a grim smile turns up the corner of my mouth. “I am Botman.” In a whirl of coat tails and unkempt end-of-field-season hair, I swoop out of the nearest window and disappear into the night, leaving behind no trace of my presence but a room full of puzzled faces.

September 29th, Sunday

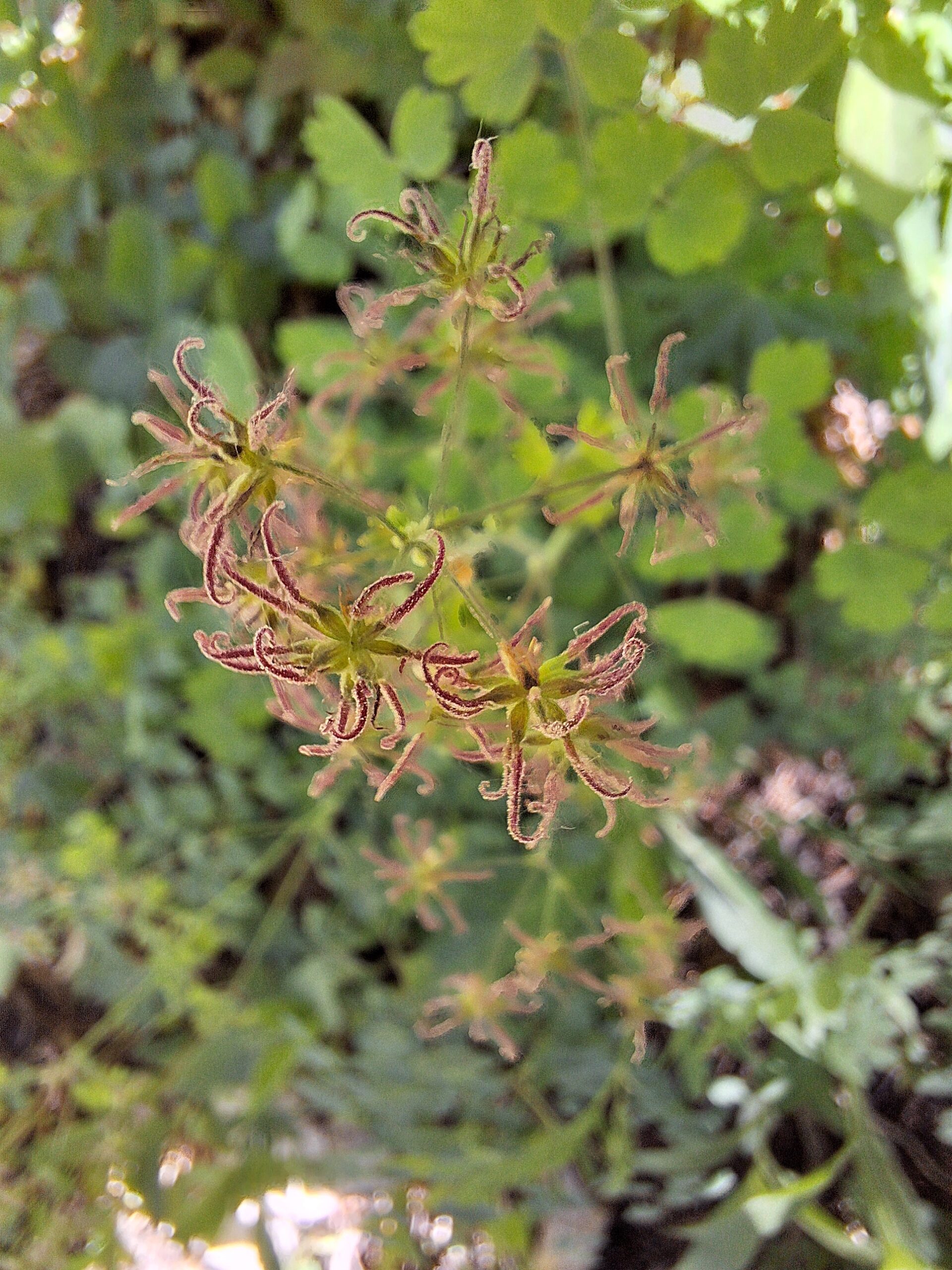

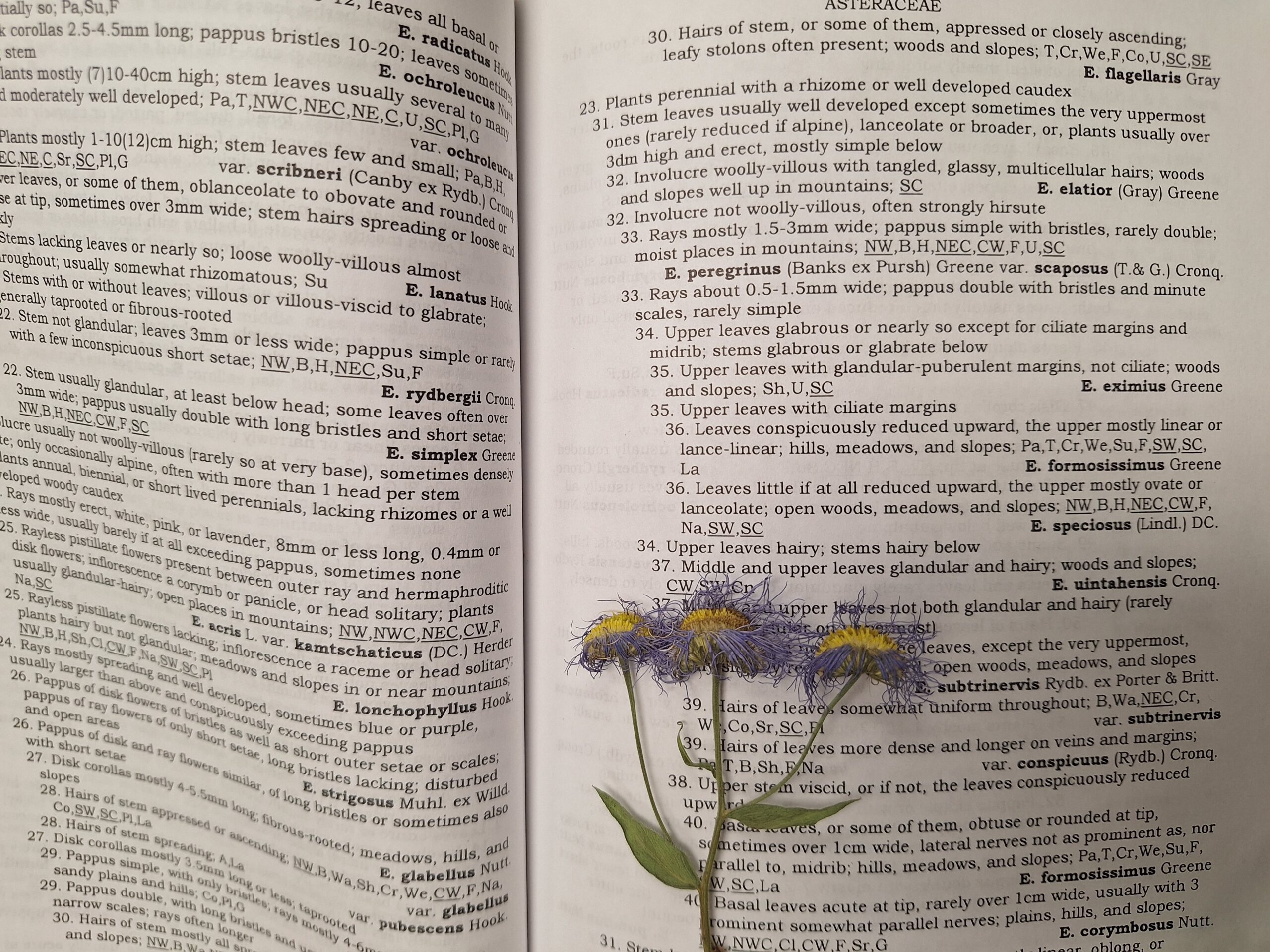

My plane touches down in Billings, Montana. As people grab their things and disembark, I’m just wrapping up a fascinating botanical dialogue with the man in the window seat sitting next to me about the intricacies of working with one of the most esoteric dichotomous keys in “Vascular Plants of Wyoming, 3rd Edition” by Robert D. Dorn. “When you collect a specimen of Erigeron, make sure you get the roots. Once you’re out of the field, it’s anyone’s guess whether that thing is perennial, or if it’s lacking rhizomes or a well-developed woody caudex. And don’t be led astray by any lead about a wooly-villous involucre! It’s usually just sub-puberulent to strongly hirsute.” I slap him on the shoulder and chuckle as I get up to leave. “Alright, uh. Thanks man,” he mutters gratefully. My gaze lifts, and it looks like everyone is off the plane! Clear aisle, not a soul in my way. Perfect. I strut briskly down the aisle and give a curt nod to the cleaning crew as I pass. There’s a job to do.

September 30th, Monday

The sun rises blood red over the Botcave (the Bighorn NF Supervisory Office in Sheridan, Wyoming), and there’s excitement—and smoke—in the air. The Elk Fire is now about 6,000 acres, and everyone with a red card is gearing up to head out to the blaze. Kaitlyn’s already at the office when I burst through the doorway. “To the Botmobile!” I cry. I grab my pack, radio, and trusty hori-hori, and fly out the door. Kaitlyn rolls her eyes, but grabs the keys to our Jeep and follows me out.

Although the fire is still miles and miles to the North, the air is thick with smoke as we ascend onto the forest on US Highway 14. Being a law-abiding representative of the Forest Service, with the emblem stenciled on the side of the ’Mobile, I know I must stick to the 40-mph speed limit, winding around every switchback curving up the mountain. But man, it feels like we can’t get on the mountain fast enough. The urge to rush to the rescue of my plants makes me wish we were going 65. I say to Kaitlyn, “we’ve got to get lights and a siren on this thing. Can you make a note for our next team meeting with the Aquatics shop?” Kaitlyn sighs. In agreement.

We crest the mountain range and it’s a relief to find blue skies overhead. Perhaps the Elk Fire won’t be as all-consuming as it threatens to be. We spend the day scouting for Artemisia tridentata ssp. vaseyana: A short, flat topped variety of Big Sagebrush, which flowers late in the season and will be our last collection. It’s all scouting and PR today, no collections. We reassure each and every family of Artemisia shrubs we come across that a heroic crew of Forest Service fire fighters and employees are keeping the Elk Fire at bay. Admiring eyes shine out of each little flowering head as we stroll through the shrubland, but I know they’re the ones who truly deserve admiration—Many will remember the heroism of the brave firefighters risking life and limb, but who will remember the humble Artemisia tridentata ssp. vaseyana who donated 20% of her seed to the cause of post-fire revegetation?

The morning stretches into the afternoon, and we head back on Highway 14. We learn that wind has been ripping along the East slopes of the mountain, angering the Elk Fire and whipping it South, nearing the highway! The Wyoming Department of Transportation has closed the highway, and we’re turned around at Burgess Junction. Drat! The Elk Fire has shown itself to be a formidable foe. A long detour South and East brings us off the mountain on Red Grade Road, and we’re met by an admonishing call from the head of the Aquatics shop upon returning to cell service. We probably shouldn’t have gone out into the field today. “Yes sir, sorry sir”. It’s big news—In just an afternoon, the fire had grown to more than three times its size! The Elk Fire had stomped across steep slopes populated by thousands of innocent Lodgepole Pine and Spruce, gnashing its teeth as it gobbled up now 22,000 acres. Who knew a fire could grow that fast in a day? A sobering lesson now stored away in Botman’s gourd.

October 21st, Monday

Nearing a month has passed since the Elk Fire began, and it’s snatched up over 96,000 acres, but is slowing to halt. The fight has been long and grueling—over 900 personnel are working the fire, hailing from many states all over the country. Miles of hand lines and dozer lines have been put in place, and fire retardant frequently cascades down from planes and helicopters. Fire fighters and red-carded Forest Service employees alike spend up to 30-hour shifts on the mountain and return as heroes.

Local communities pour out their gratitude. This morning, as we drive through the town of Buffalo to approach the south side of the mountain, signs in the windows of many businesses read “Thank you firefighters!” (“and botanists!” where I’ve had a chance to make some edits).

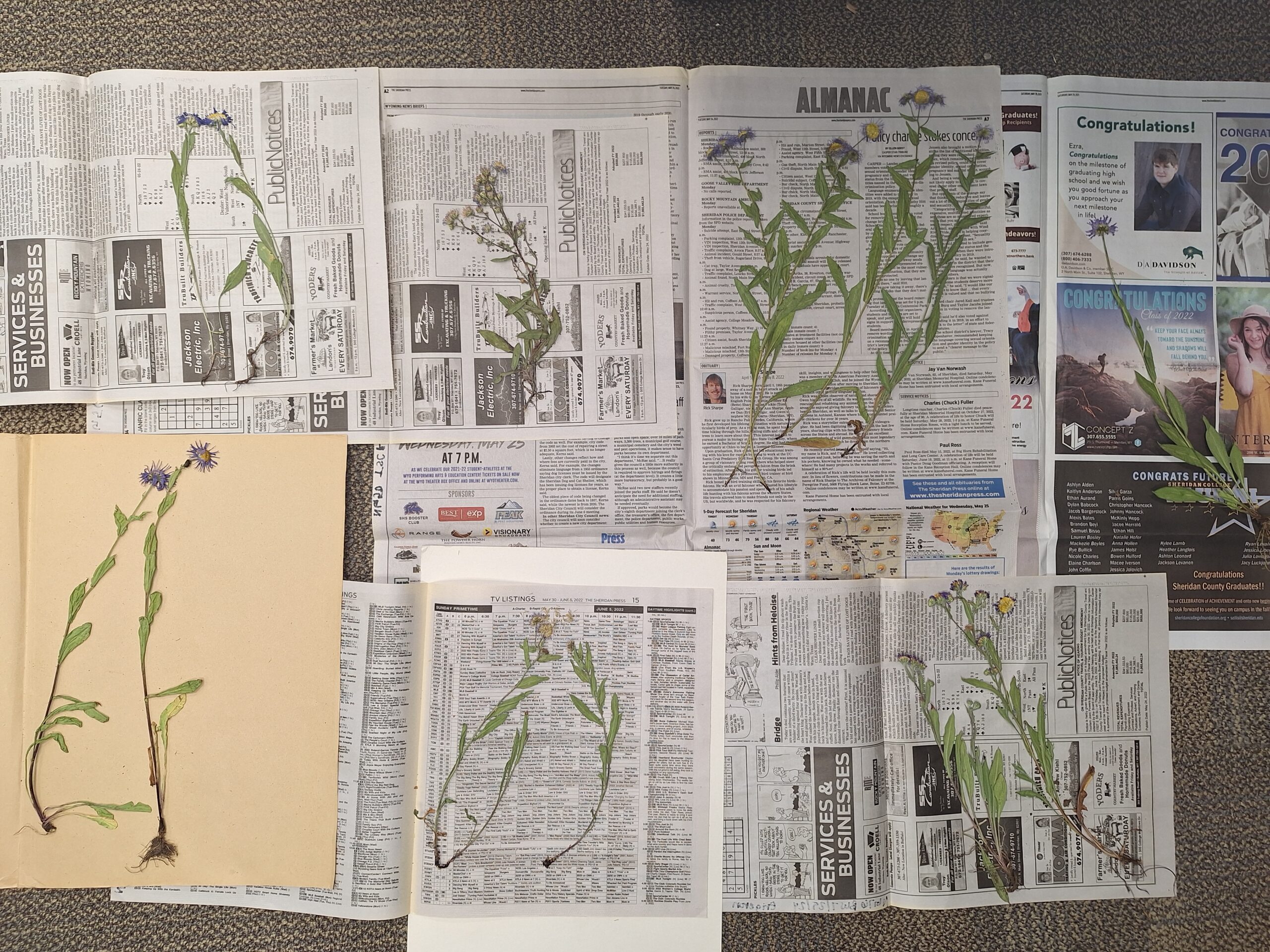

We’ve been hard at work this month too. Confined to the Botcave for most of the month, keying out plants, mounting herbarium specimens, writing an end of season report, and preparing our seed to be shipped off to the Couer d’Alene native plant nursery and seed extractory—a lot of people think it’s action, action, press conferences, and more action, but the life of a botanist isn’t always as glamorous as you might imagine.

It’s now later that day, two hours into a collection of Artemisia, hunched over the small shrubs which blanket the hills around me as far as the eye can see. I wipe the sweat from my brow and straighten up to scan the horizon for danger. A deep and powerful rumble sounds from behind… with plant-like reflexes, I whip around to face the impending threat!

Whew! It’s only a member of the public, approaching in his old truck to speak to Kaitlyn. He must inquire about our duties here, because I hear Kaitlyn give him the run down: “we’re collecting seed, which we’ll ship off to a native plant nursery for the production of even more seed, which will come back to the forests for roadside plantings, restoration projects, and post-fire revegetation.” As far as cool catchphrases go, it doesn’t roll right off the tongue, but it’s sufficient to produce a salute and a “thank you for your service.” It’s the answer we’ve given all summer, but as the Elk Fire raged, that phrase has rattled around in my brain, and now the necessity of our work is close at hand. Our seed may indeed make it back to the Bighorn in coming years to rescue singed and demoralized native plant communities. Not all heroes wear capes—some wear a hard hat and fire pack. I’ve heard it said also that some wield a hori-hori.

The battle against the Elk Fire has been fought and won, but not without plant casualties. I look into my paper bag and see amidst the chaff and seed: hope. The journey for these little seeds starts here, and it may end here. It will be a long journey. But plant life, helped along by its (super)human champions, will prevail over the Elk Fire here on the Bighorn National Forest. Native plants will reclaim their soil.

Kaitlyn looks to be about done with her conversation, and the engine of the man’s truck revs up to leave. We’ve gotten the seed that we need from these Artemisia, and it’s time for us to head home. I lift my head, give a final salute to my friends the sagebrush. I turn and, with a knowing smile, fire off a quick volley of finger guns at the man in the truck before I steal away towards the Botmobile. Swelling with pride, it’s moments like these that I know deep in my heart, I am Botman.