What is it that makes our lands valuable and worth managing and protecting? There are many reasons to list, but this week I want to focus on Paleontological resources.

I used to think the drive to visit my sister in Southern California was quite boring. I didn’t think there was much to look at in terms of scenery and Interstate 5 isn’t very curvy. Curves are fun, right? I did what most people do to prepare for a long boring drive: make a mix-tape/playlist of driving music, borrow some books on tape from the library (I say “books on tape” and “mix-tape” even though we all know I’m talking about CDs because “books on CD” and “mix-CD’s” just doesn’t have the same ring to it), charge your phone so you can call a friend on the way, and of course stock up on snacks. I will go a long way to distract myself from the monotony of a long haul.

My time spent out in the field has certainly changed my view of the stretch of land between the Bay-Area and Southern California. Now when I look out the window I’ll have something else on the brain. To see part of the reason why, let’s take a look back in time. 65 million years ago California’s coastline looked quite different than it does today. I like Richard P. Hilton’s description in Dinosaurs and Other Mesozoic Reptiles of California: “By the Late Cretaceous, the western edge of the Sierra Nevada had been eroded back and the sea was flooding into the areas of what are now the low Sierran foothills… Numerous fossils were deposited offshore from the ancestral Sierra Nevada in a marine environment between 80 and 65 million years ago”.

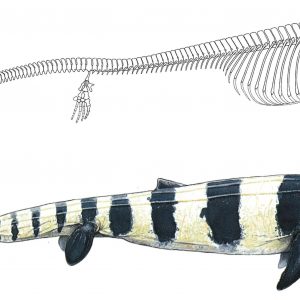

Parts of the lands I’ve been helping to manage happen to be in the Moreno formation of the Panoche Hills (west side of the San Joaquin Valley). The formation contains the highest diversity of organisms from the late Cretaceous period in the western United States. During the course of my internship I had the opportunity to explore the Moreno shale formation and discover some of the fossilized treasures it yields. Among other things, these fossils provide us with a wealth of information to better understand evolution and the make-up of past ecosystems.

Click on the pictures below to learn more.

- North America 65 mya

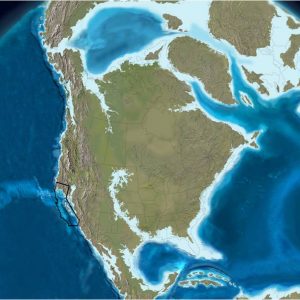

- Present day North America

I’ll still do all those things previously mentioned to prepare for the drive, but now I feel I have a deeper appreciation for the land around me. Now I can share what I have learned about California Paleontology with my passengers whilst annoying them with my taste in music. So next time you’re passing through you should stop by and take advantage of your public lands or at least think about it.

-Aaron Thom (Hollister BLM Office)

If you would like to learn more about BLM paleo-resources check out the following link: http://www.blm.gov/ca/st/en/fo/hollister/paleo.html.

Quickly, however, PHP won me over. The chaparral doesn’t have jaw-dropping mountain vistas or the grand splendor of coastal redwoods, but it does offer a quiet, more dignified beauty to those willing to look beyond it’s rough and often spiney exterior. Hidden among shopping centers and private homes lies a biological wonderland. Over 740 distinct plant species grow here–that’s 10% of California’s total native plant biodiversity in a tiny fraction of the state! Visiting PHP may include a leisurely hike along the interpretative trail, attending a naturalist-led bird & botany tour, or simply enjoying a moment alone along the S. Fork American River.

Quickly, however, PHP won me over. The chaparral doesn’t have jaw-dropping mountain vistas or the grand splendor of coastal redwoods, but it does offer a quiet, more dignified beauty to those willing to look beyond it’s rough and often spiney exterior. Hidden among shopping centers and private homes lies a biological wonderland. Over 740 distinct plant species grow here–that’s 10% of California’s total native plant biodiversity in a tiny fraction of the state! Visiting PHP may include a leisurely hike along the interpretative trail, attending a naturalist-led bird & botany tour, or simply enjoying a moment alone along the S. Fork American River.