Well, yes, we can find rare plants. The question really is: How many of the rare plants that are present in an area can we find? That doesn’t fit as well in the post title box, though.

One of the nice things about studying plants is that they are much more cooperative than animals. They don’t hide from you, run away, have large home ranges, or migrate. For those of us trying to survey them and map their populations, this is convenient. Nonetheless, not all plants are easy to find. There is basically a spectrum of survey-friendliness in plants. At one end, we might have something like Sequoia sempervirens: it’s big, easy to spot and easy to identify, and it lives for a very long time. At the other end, we might have something like Euphorbia rayturneri: it’s tiny, hard to spot, you can’t ID it without a hand lens, and it’s ephemeral. You can’t really find it at all unless weather conditions are right, and even under ideal conditions it’s going to be difficult to pick out from any distance or distinguish from the other prostrate spurges that are common in the area. Most plants, particularly in desert areas, are going to have at least one of these characteristics that make surveys difficult. So, today I’m going to give a brief example using one of the species I’ve already discussed several times on here: Peniocereus greggii var. greggii. For a desert plant, it’s reasonably large, generally 1 to 3 feet high. It’s easy to identify. It’s pretty long-lived. It is hard to spot, however. Here’s a large plant, pretty unobscured:

And here’s what you’re more often dealing with–a cactus hiding inside a shrub:

So, let’s suppose you’re surveying an area to ensure that some upcoming project won’t harm our peniocerei. What kind of detection rate is achievable? And, given that detection rate and some understanding of the density and spatial patterns of Peniocereus greggii var. greggii populations, how many individuals can we expect to harm simply because we couldn’t find and avoid them? Those are difficult problems and, instead of trying to answer them in any kind of rigorous fashion, I’ll just provide some anecdotes. We have three populations of Peniocereus greggii var. greggii that were thoroughly surveyed back in 2012, and for which previous CLM interns began a monitoring study in 2013. They’re just about our best case for high detection rates.

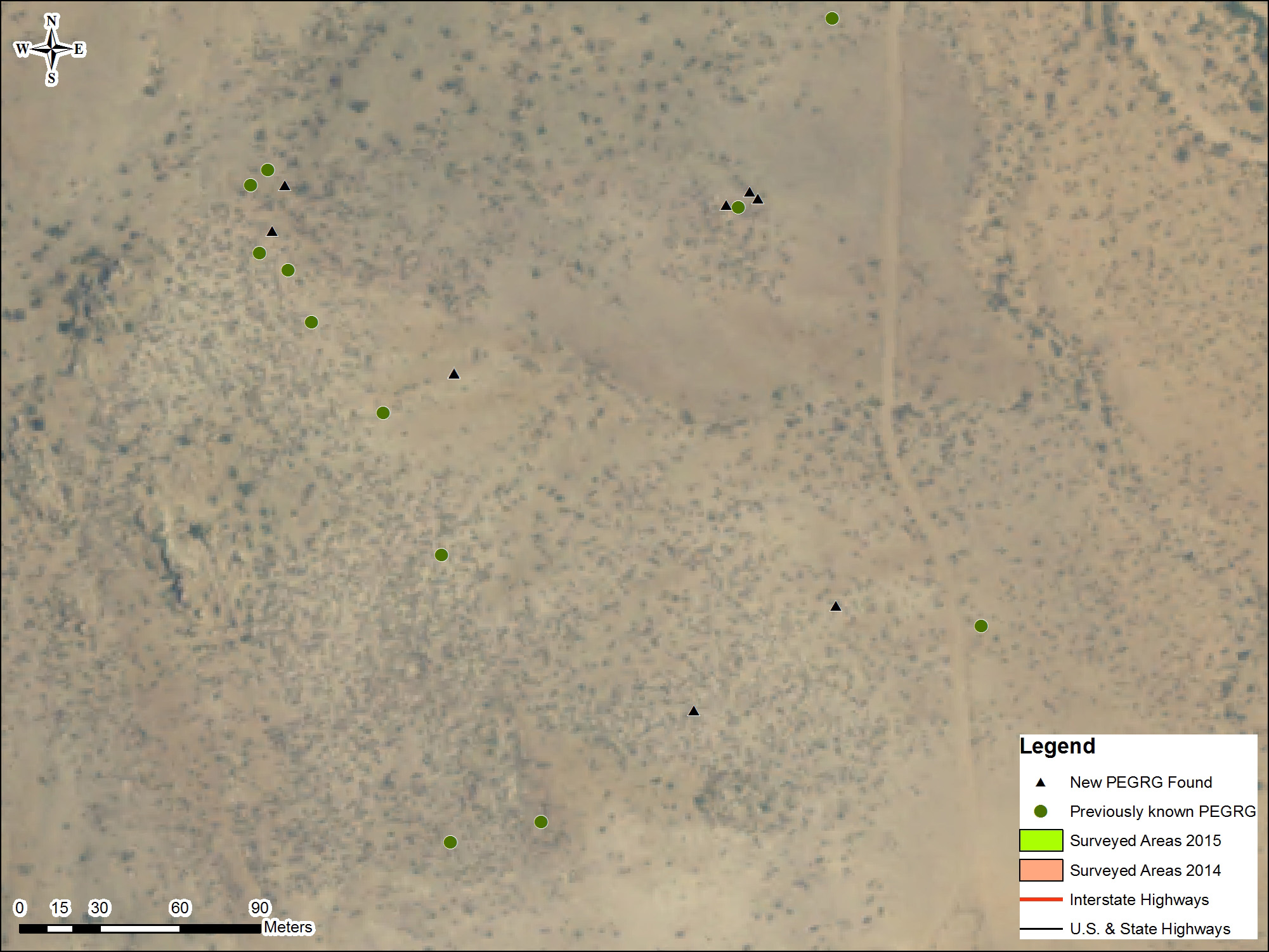

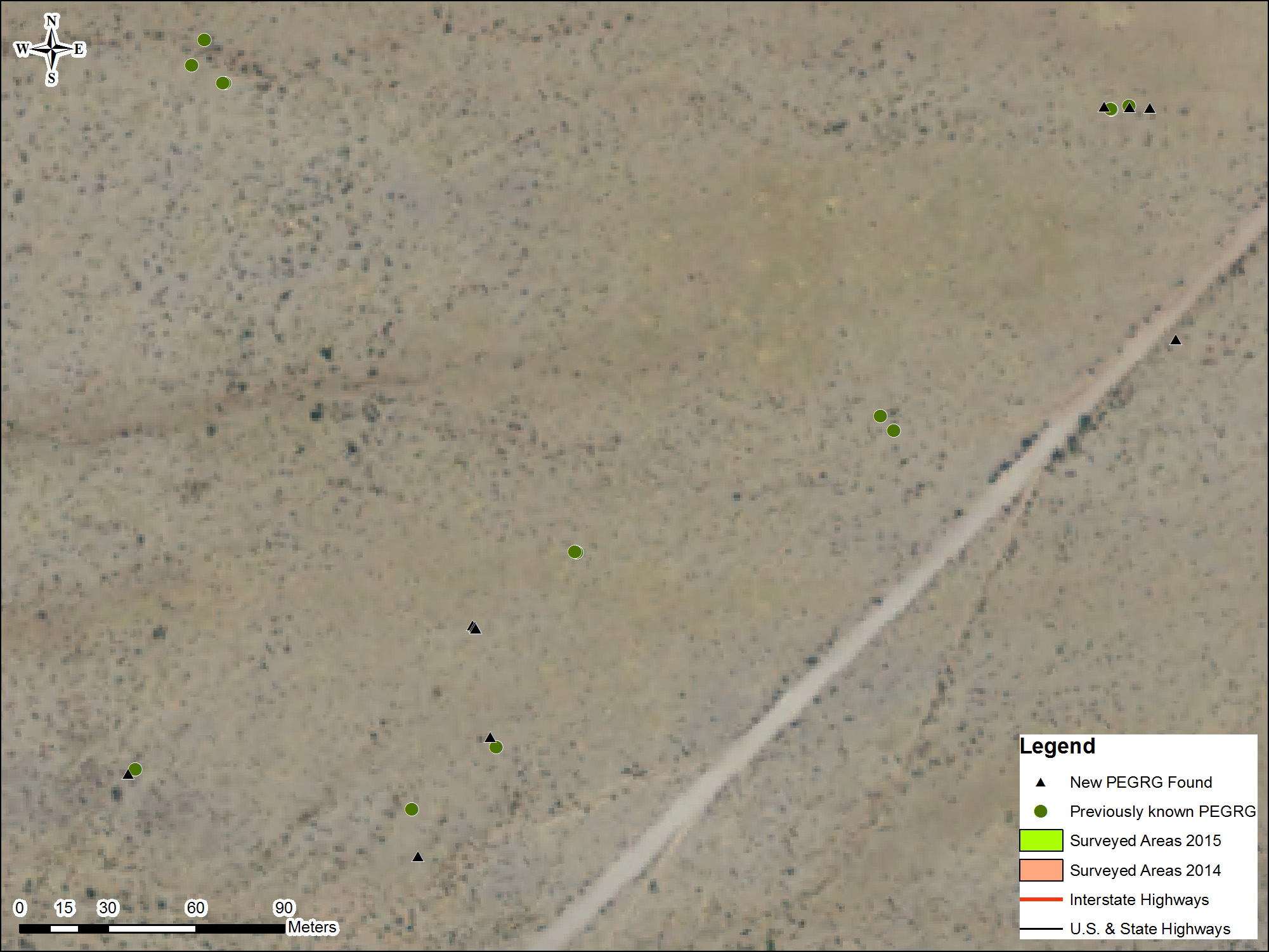

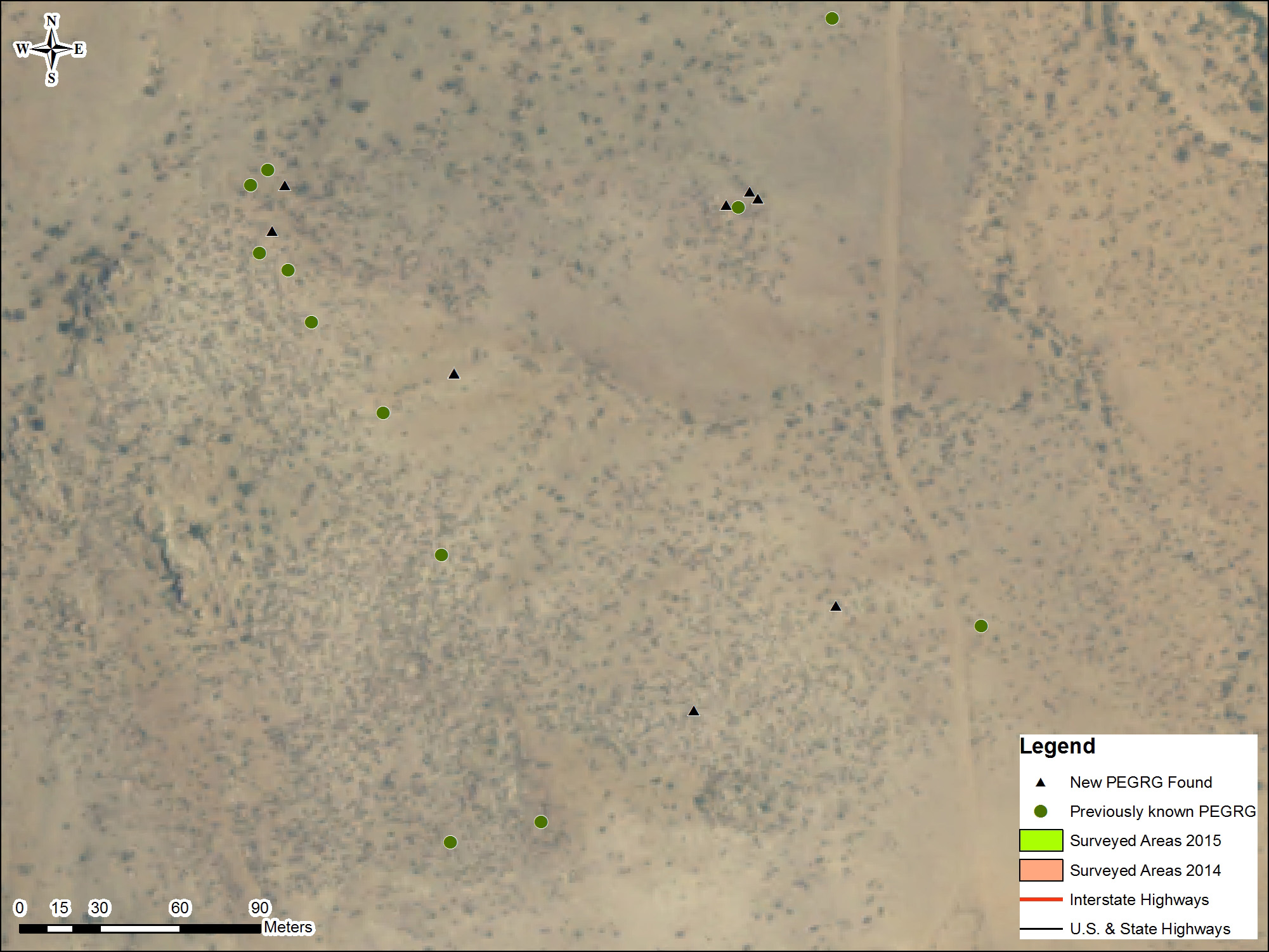

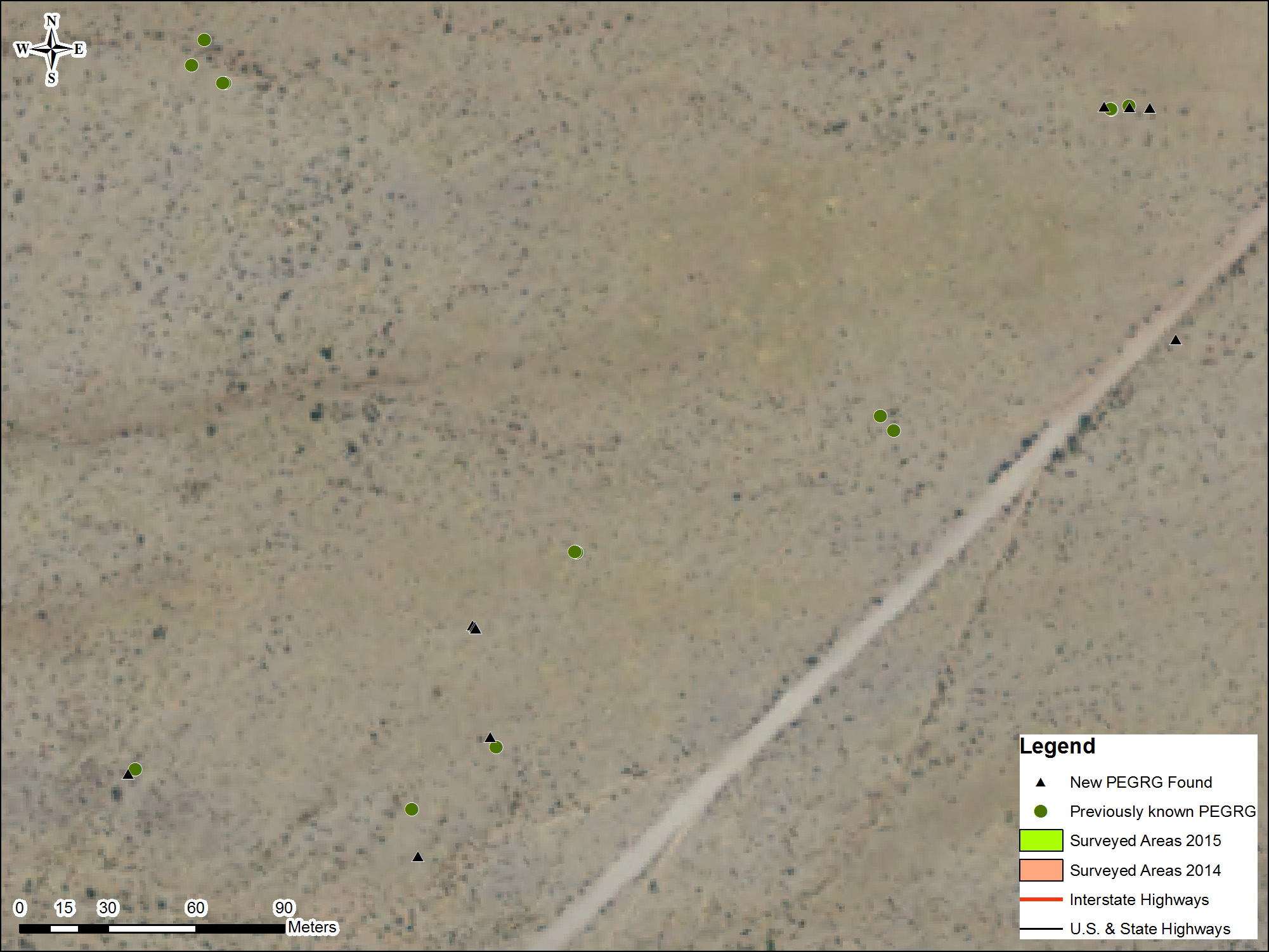

This year, my interns and I went out and remeasured plants in two of these populations (Steins and Swallow Fork). In the third (Big Cat), I went out back in May with several other botanically-inclined folks kind of poking around (I was just hoping to find plants in flower, and luckily I did!). In all cases, we found new plants. In the Big Cat population, three of us were wandering around for two or three hourse, mostly checking on previously-known individuals. We found ten new plants in an area where 32 were previously known. For the Swallow Fork population, we found 12 new individuals where 26 were known previously. In the Steins population, we found 58 new individuals, where 113 were previously known. So these put very approximate upper bounds on the detection rate in previous survey, somewhere around 67%. I’m sure if we had done full surveys in each of these areas, we would have kept finding more individuals, so the actual detection rate is probably substantially lower. Now here’s the interesting thing: many of these new individuals we found were right next to previously known plants! It was fairly common, in all three populations, for us to be looking for one of the previously GPSed plants, have a little trouble finding it, and stumble across another plant a few meters away. In all but a couple of cases we were eventually able to find the original GPSed plant, so it’s not just some kind of GPS error. Here are a couple of maps of of portions of the Steins and Swallow Fork populations to illustrate–notice the scale at bottom left, we’re dealing with pretty small areas:

Often, the previously known plants were in worse shape and harder to find than the “new” plants. So, how did the original survey crew find those beatup, unhappy plants while often missing a big healthy Peniocereus a few meters away? Well, they almost certainly didn’t. There’s a very simple explanation that wouldn’t have occurred to me. Drs. Ed and Beth Leuck mentioned to me about a year ago that Peniocereus greggii var. greggii that they’ve been monitoring seem to die back to the ground every now and then, particularly after flowering. Oh yeah, I forgot to mention: these guys have big honking tubers. So they can die back to ground level, then pop back up next year. This is very odd for a cactus. It’s also pretty odd for a tuberous plant. Most tuberous plants, at least in our climate, don’t have woody above-ground stems that persist for a few years. So we’re dealing with a tuberous cactus that has somewhat ephemeral stems. After the stems die back, they are incredibly difficult to spot. You can be within a meter of a GPSed individual and still poke around for five minutes until you find that one dead stem that isn’t like the others. So, as a cactus, you would think that one of the things Peniocereus greggii var. gregii has going for it is that you’re dealing with a long-lived plant that is basically going to be where it is and be findable over long periods of time. Nope. So that moves it a notch or two away from the survey-friendly end of the plant spectrum. I guess the moral of the story here is just that, even though plants are easier to keep track of than animals, they’re still kind of a pain. And most plants are probably going to have some weird quirks like Peniocereus, you just won’t know about the quirks until you’ve spent some time with a particular species.

Now a few miscellaneous pictures.

Is it a legume? No, it’s a spurge, Phyllanthus abnormis!

And here’s a Pituophis catenifer sayi who was not pleased to see me: