On my last post, I talked a lot about one type of restoration project that can be found on old, mined lands within the Monongahela National Forest and in Appalachia, but not all restoration projects that take place on the Monongahela are like the one I described last time. A lot of restoration consists of smaller scale projects like invasive species removal in locations all around the forest, campsites, and roads including scenic highways. Removal of invasive species can include projects like hand pulling of herbaceous species like garlic mustard, using loppers to cut down larger woody shrubs, or spraying foliage and/or cut stump herbicide to get rid of other species. This removal is important to do regularly because it keeps invasive species from spreading throughout the forest and taking resources away from important native species.

A third restoration technique to help support the growth of native species in Appalachia is fire ecology. This is an interesting land management tool that can be used to rejuvenate certain ecosystems and allow the growth of healthy forests. Some ways to make the forests healthy is through reducing leaf litter and downed limbs to increase the habitats to promote the growth of native plant diversity. Specifically, fire can be used in Appalachia to help maintain the oak and pine forests to increase the openness of the forest understory, creating sunlight to the forest floor, and promoting seed germination. It can also help reduce the completion of survival of competitive species by limiting the growth of these competitive tree species like red maple, tulip popular, and white pine which tend to out compete some of the other species when there is an absence of fire. It can promote the native grasses and wildflowers, thin crowded forests which can help prevent disease and insect pest outbreaks and it also increases the food abundance for native wildlife like bears, deer, and birds. It had been seen through surveys that with a lack of fire implementation there has been diminished oak and pine regeneration, and lack of herbaceous groundcover from their historic range of variability.

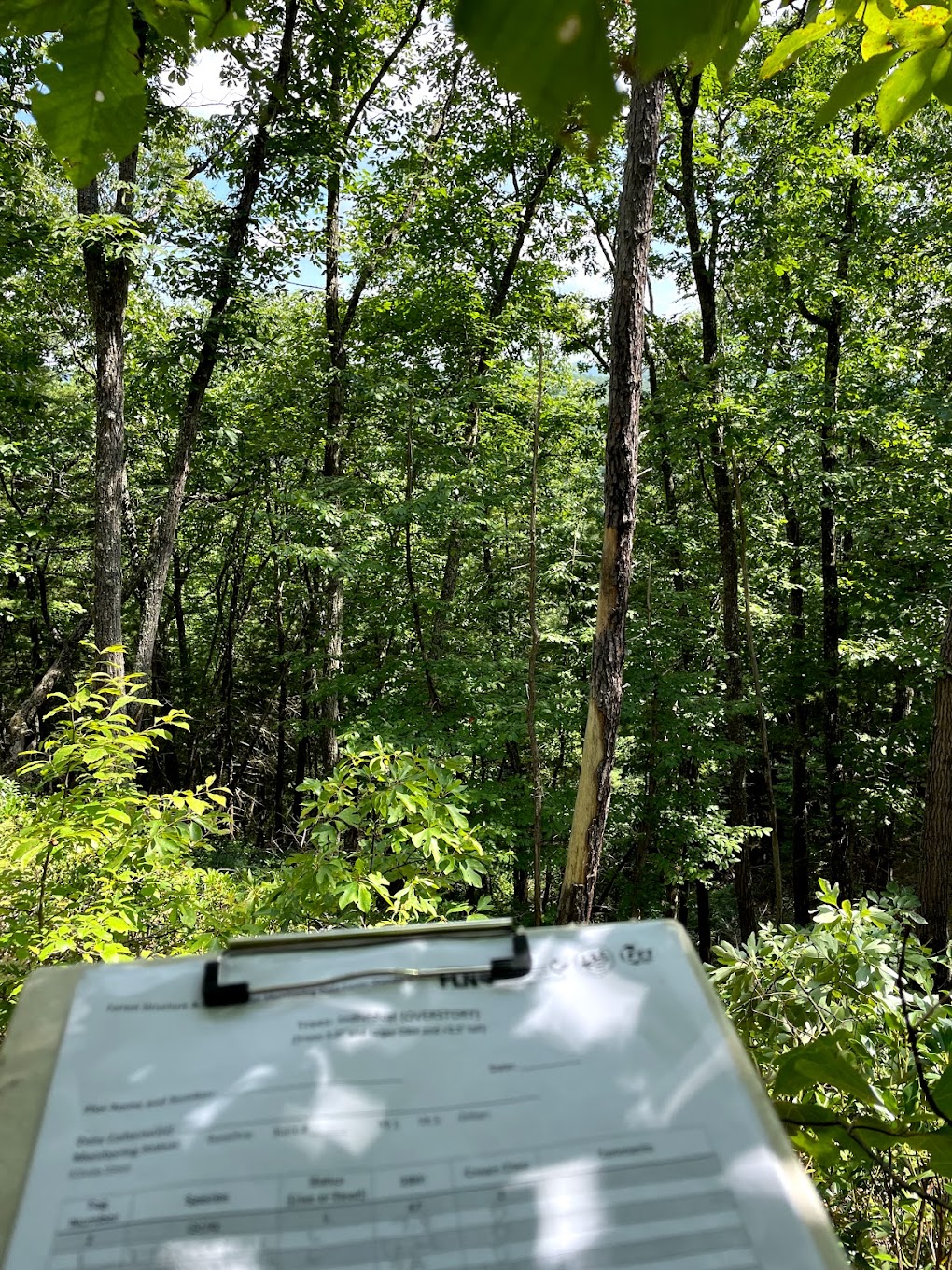

When it comes to the National forests in Appalachia, fire ecology is used specifically to increase the native diversity. The past couple of weeks I have had the opportunity to help with the pre and post burn tasks and learn a lot about fire ecology in practice. For these tasks I helped with pre- and post-burn surveys of the fire plots. Using a GIS software, the survey location within the burn units was randomly selected and was given to the forestry tech to record the pre-burn survey. This survey includes recording the canopy cover frequency, ground cover frequency, woody shrub density, and the trees in the area. This is an important step in the prescribed burn process so that there can be a baseline of the vegetation within the burn unit to compare the post-burn surveys to in the future. The post-burn surveys typically happen in the growing season within six months after the burn, a full year after the burn during the same season as the pre-burn surveys took place, and then another survey five years after the first burn. These post-burn surveys are important to compare the vegetation growth within the burn units over the course of five years.

Assisting with both the pre- and post-burn surveys has been extremely interesting because it has given me the opportunity to look at another form of land management that is taking place in the Monongahela. Within the forest service, fire ecology has been a recently new technique to use for land management. The methods and research on prescribed burns continues to evolve and being able to help with the surveys allowed me to gain insight on how land management continues to improve over time with research and practice. I have been able to learn so much from working with the fire team and look forward to continuing to help them on their surveys and learn more about prescribed burns within the Monongahela!