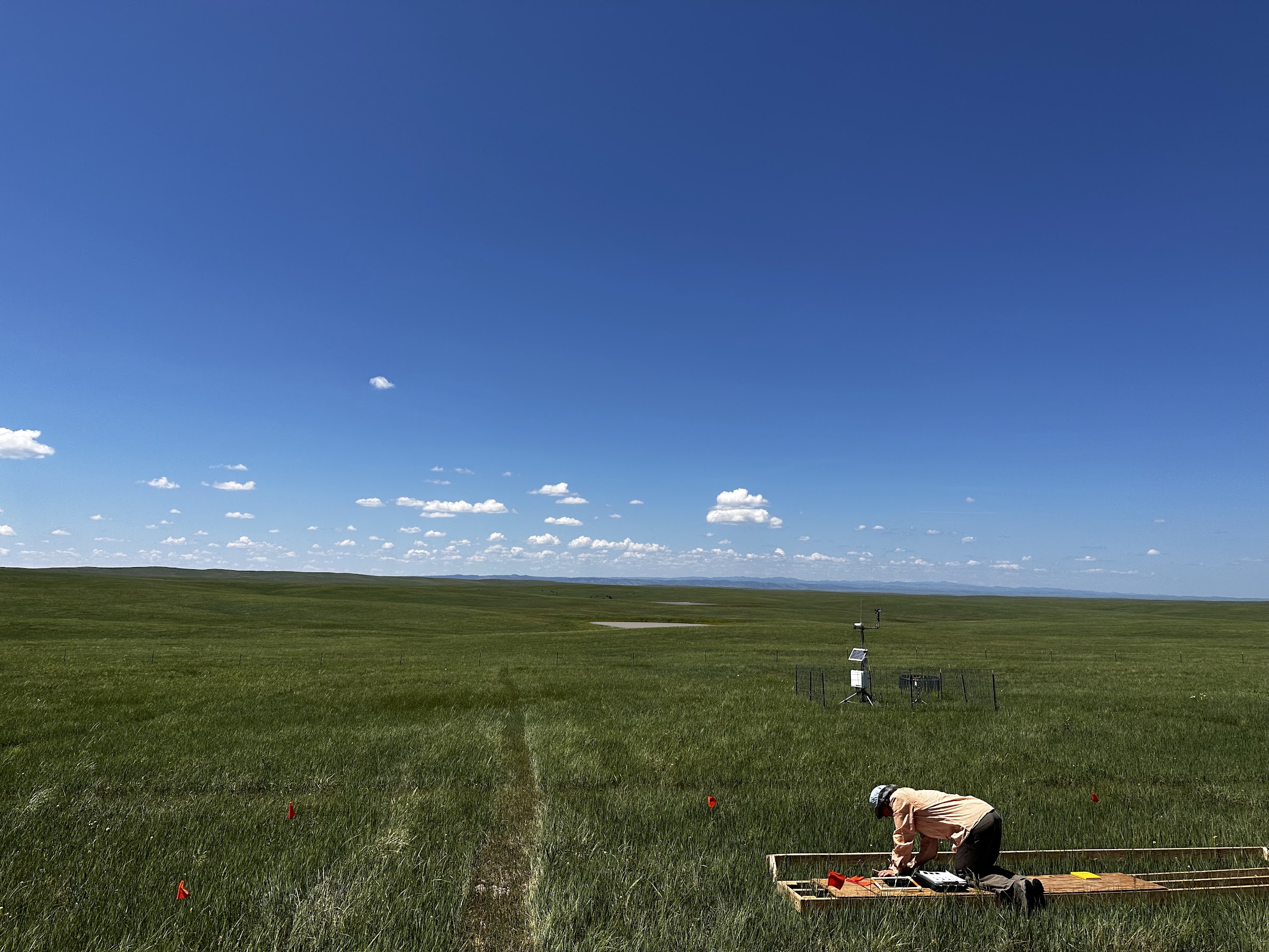

Well. This week, my first, went about as well as I had hoped it would. Despite the majority of the week being set in necessary trainings, I had a wonderful time getting to know my fellow co-workers. One thing I really enjoy about field work is its attraction of transient folks coming from all different kinds of places. Through the lens and experiences of others, I feel like I am traveling from each story I hear. Towards the end of the week, I was able to find time between all the trainings for a field day with my co-intern here in the Helena-Lewis and Clark National Forests. She has been here for approximately a month longer than I, which means she is an excellent guide and resource to me as I get started here. I am incredibly grateful for this fact and for her patience with me and my various questions. I am curious about the plants (of course!), the landscape, office ins-and-outs, potential populations to collect from, her personal experience so far, habitat typing and how it relates to seeds, and many more questions surely to come.

As we make our way from the bunkhouse towards Monarch, MT and down and around various Forest Service roads, we get to know each other through light conversation. We make our way through Douglas Fir forests, Lodgepole pine forests, before the forests open up to a beautiful and lush meadow. Here, we note Geranium viscossissimum, or Sticky geranium, which is fully in flower. It has a beautiful pink-magenta colored flowers, and because it is a perennial species, it seems to stick out just slightly above its surrounding counterparts. It’s a wonderful addition to the landscape and I am happy to be on the lookout for it.

Suddenly my co-intern is stopping and safely pulling to the side of the road. She’s spotted a rocky outcrop that could house another one of our target species: Phacelia hastata. She hops out, dutifully dons her Forest Service issued radio and bear spray before making her way to the outcrop, a procedure with which I will have to quickly become acquainted. “It’s here!,” she shouts to me as a scramble up the slight rocky slope to join her. The silverleaf scorpion weed. What a beauty. It’s low-growing and on an otherwise mostly barren hillside aside from some distant roses. It’s hard to believe that this rocky, seemingly nutrient-deficient place is where anything would choose to grow. Then again, I guess a seed doesn’t have too much choice in where it is grown.

We make our way through this long meadow and again through some forested areas. The habitat seems to change every few miles as we ascend and descend, loop around and back down, etc. Suddenly, we are bumbling up and along a narrow, steep and rocky road that made me forget to look around completely! As the road widens and flattens out, I am drawn again to my surroundings and find the trees up here on the hilltop are much smaller and more sparse…Ponderosa pines. Wildflowers here are abundant and my co-intern again is very helpful in pointing out new ground-dwelling friends, along with some features of each that set them apart from look-alikes. We are on the hunt for a specific set of 40 or so wildflower friends from whom we will hopefully be able to harvest their babies in the coming months… Kind of weird when you put in that way.

We continue down down down, then up and up and up until we come to a the top of a peak. Something pink flashes from the corner of my eye and triggers a memory of Pedicularis, commonly known as lousewort or Elephant’s head because of the shape of it’s flowers. It’s a gorgeous and striking little plant and I seemed to remember, from the brief look I’d had at our list, that there was one on it. I ask to stop, and we both get out to take a look. The guide to Montana vascular plants comes out. Not our guy; however, with the sun shining up above, the gorgeous view in all directions, and it being just after noon, it was a perfect time to stop for lunch. Another perk of the job.

After lunch we switched drivers and made our way around a large loop of mostly Forest Service land to continue scouting populations. As we made our way, one common theme repeated throughout the journey from peaks to rivers to meadows to dense forest: this area, the Little Belt Mountains, a small section of the Rockies, is as Victor, our mentor here at the Forest Service, put it, “a land of extremes.” It is evident from the drastic and sudden changes in vegetation, from the blown out tops of thick-trunked trees, the varying waterlines in creek and from the way seeds are willing to germinate in even the most destitute of places. Not only this, but if the weather I’ve experienced here in the Little Belts thus far in this the least extreme part of summer, is any indication of what might be imminent in the more harsh parts of summer and winter, I would say the plant life here must be prepared for all varieties of weather, and for changes at the drop of a hat. This is all a convoluted way of saying this is a land of extremes, indeed, and my interest is thoroughly peaked.

More next month!