What will winter bring

When I last left off I had traveled to Nebraska to see the Eclipse after which I asked myself, what could top experiencing the moon moving in front of the sun and turning the world dark for 2 minutes as humans all over the States stared in disbelief?

The obvious answer is collecting more data on Sclerocactus glaucus, of course!!

What finally brought us full circle for the field season here at the BLM Colorado State Office was the return of our crew to Montrose to gather data on both Eriogonum pelinophilum and S.glaucus. As we drove over the Southern Rockies on the 70 musing about our return to the cactus that we started this year off monitoring, we looked out of our windows at the changing of the Aspen leaves and felt a little bit of closure to the field season. What a way to go out.

The changing of the leaves

But what lead us back for more data collected after all these months? Basically the years and years of data collected on the Sclerocactus have come to a climax. Carol, my mentor, has spent much of her time at the BLM working towards de-listing this species, and now is the time. Our return to the cactus was brought on by a need for targeted data to make the reporting more sound and complete.

To be honest, when I type those words, de-listing, as an ecologist, I feel a little guilty. Why would we want to de-list a species when the Environmental Species Act (ESA), that it is protected under, is meant to, well, protect it?

I think this is one of the areas that has been the most enlightening to me throughout this internship. The more that I learn about topics that I had thought I understood, the more I realize that one can feel informed and still not actually fully grasp the subtle nuances of the complex field of threatened and endangered plants.

Let me explain, the ESA was was ratified in 1973, passed by a democratic-majority congress and signed by President Richard Nixon only a year before he resigned his office. This act was created in order to preserve not only the plants and animals that were under threat from human and environmental factors but also to protect the environment they existed in. That is a tall order for an agency like the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (and NOAA fisheries) that is tasked with its implementation. In the beginning, listing was used to protect anything thought of as needing protection under a myriad of potential threats including industrial growth (think reservoirs, mining, and human expansion) and recreational use (including our own species of interest Astragalus osterhoutii and potentially Corispermum navicula due to the Wolford Dam and off-road vehicle use, respectively). Also, in the beginning of the Act many plants were listed with good intention but with less than adequate data.

Here is where the problem lies. In Colorado alone there are 16 listed plant species of the around 900 plant species listed for the entire United States. Now, that may not sound like a very large proportion, but under the current funding level for the US Fish and Wildlife Service and given the amount of constant monitoring required for the responsible management of the populations across the states, it is a lot of work. That is where we come in and why Carol has worked so hard to monitor these species. This work is also done at the District Office level within the BLM CO, who would normally completely shoulder the load, but in this case they are treated with two levels of attention.

All of that sounds grand, but the issue becomes particularly thorny when, in the case of S. glaucus, we come to find that the species is more abundant than originally thought (recall the plants listed in the 70s with little data). Given the limited resources available for monitoring, it quickly becomes untenable to funnel precious resources toward monitoring and managing species that may never have warranted protection in the first place.

Here comes the reality of de-listing. Resources currently allocated to species that are more abundant that previously thought could be used to help a species that are actually in peril or to identify species that might not be known to be in peril. Just think that in the lifetime of the Act there have only been 31 de-listings of listed plant species. When you consider that the intention of the ESA is to recover imperiled species, that is not a large success rate.

Additionally, the use of the Act has changed over time. Remember how I said it was used to protect plants once they are listed? Well, an ESA listing triggers a series of mandatory regulations placed on the species, and the land that it inhabits. There are even critical habitats that are protected regardless of where the plant is found (public or private). Which, as you can imagine, is not something that landowners or entities that could make money off the land, appreciate. So instead agencies have been working to use the Act as a last resort, instead of looking to list immediately they instead promote conservation agreements which are agreed to by a range of stakeholders to protect the plant in question. This happens when involved parties recognize that it is in everyone’s best interest to avoid a listing and decide to come to the table to proactively agree to terms to protect the plant to avoid listing in the future.

I am rather impressed by this idea because it means, ranchers, land managers, mining companies, energy companies, states, and other interested parties come together to resolve differences toward a common purpose. What a concept, but like I have mentioned with P. grahamii, conservation groups don’t always see these agreements as a win. Instead, these groups can be stuck in the old mindset that the ESA is the best way to protect any species. Unfortunately, if conservation groups get their way, that means that many individuals will be subject to regulations and restrictions forced upon them by the ESA, without much recourse save open rebellion against the US Government, which doesn’t typically end well as we’ve seen in the case of the Malheur NWR takeover of 2015. With a listing comes bitterness from industry and a lot more work for regulating agencies (cough cough BLM). It’s a delicate balance. On top of all this, often the protections that come through a collaborative stakeholder based approach can be better tailored to a particular plant and region.

So all in all it is a muddled up, bureaucratic quagmire that can be challenging for different parties to see from the other side’s perspective. But, fear not, that is why we have competent hard working people like Carol and Phil working on it!

Our last outing of the year was actually an overnight trip to Walden where we looked at Corispermum navicula, which, to be honest, was one of the more fun monitoring sites. This plant is an annual (the only one we monitor) and thus we monitor for frequency. This meant walking around the North Sand Hill Dunes for hours with the Esri Collector app on an iPad trying to place ourselves on 300 randomly selected points in search of the plant. What an adventure, with only a few cups of sand found in each one of my shoes by the end.

Brooke an I on the quest for C. navicula

Thanks goodness for winter! I always love the field season and love being outdoors for a while, but I can feel my hands itching to crochet and my sewing machine getting lonely (I know, I am a 1950’s house mom) and I am excited to experience Colorado winter (or any winter at all really)!!

oh, also I ran a marathon, which was painful

A bag of 1,000 Cercocarpus montanus seeds

Until next time when I write about mostly data management and Excel!

Taryn

Colorado State Office

Keep an Open Mind

Vernal, Utah isn’t well known for it’s tourism. It could be someday; it is close to attractions like Dinosaur National Monument, Flaming Gorge National Recreation Area, Sheep Creek Geological Loop, Red Fleet State Park, the Uinta Mountains, Nine Mile Canyon, Fantasy Canyon, and the Book Cliffs. ATV and dirt bike trails are popular here; it’s a bit like Moab without the traffic. It’s also a mecca for paleontology. Just look around town, there are dinosaurs everywhere. There are also crude oil tankers and lifted trucks around every corner. For nine months now, I’ve been a Jeep in a sea of lifted trucks. If Vernal is well known for anything, it’s as the crude oil center of Utah.

Fantasy Canyon

This place doesn’t get a lot of love from outsiders, but for those willing to take a closer look it has a lot to give. As a botany intern with the Bureau of Land Management, I was able to take that look. There are nearly 50 unique plant species that evolved in this area and can only be found here. Many of those species rely on the region’s oil shale, which is also the source of local economy and culture.

White River Beardtongue (Penstemon albifluvis) only grows in oil shale. It is much more showy when in flower, but always a cool find due to it’s rareness.

A federally threatened species of Sclerocactus

A native bee pollinates Pallid Milkweed (Asclepias cryptoceras).

The plants don’t have to be rare or unique to be cool. My internship focused on the Seeds of Success program, so I collected from the common species that can hopefully be useful for future reclamation projects.

This Small-leaf Globemallow (Sphaeralcea parvifolia) was guarded by Phidippus octopunctatus. At 2.5 cm long, this is one of the largest species of jumping spider. There’s no common name, so.. now calling it the Tuxedo Spider, thanks to males like this keeping it classy.

Sand-dune Rubber Rabbitbrush (Ericameria nauseosa var. turbinatus)… challenges of life on an active sand dune

Vernal has grown familiar and comfortable for me. I finally memorized the labyrinth of unsigned dirt roads into a mental map. I also appreciate the ability to drive on main roads for 80 miles without seeing another human. I will miss the familiarity, the species, and the people I worked with closely. To future interns, I say keep an open mind and this place will grow on you.

A Bittersweet moment. Yes, the Green River was really that green. -Gates of Lodore, Dinosaur National Monument, CO.

October Snow

I’m so excited: it’s started snowing.

The days have still been mostly sunny and warm, but last week precipitation was falling in solid form. It didn’t stick around on the ground, but all the ridges & buttes had a powdered sugar frosting!

Last week I went out to look for sagebrush seed: it’s an important habitat plant for sage grouse and other desert animals, and can get wiped out in wildfires. Sagebrush species have very subtle differences and can be agonizing to identify, so standing around in 40F, cloudy weather with winds scouring you at 15mph does not make it any easier.

Cold, and WINDY

A little nicer in this canyon

That day before heading out I was confident in my weather forecast of sunny but cool, so I was totally caught off guard when the stretch of desert I was in whipped up a freezing flurry storm!! It wasn’t quite sleeting on me while I was walking around, but I drove through whirling white snow clouds to get back to my office. When I returned, the buttes around the office were dusted with sleety snow!

Butte ridge with a little accumulation

Big snowflakes!

I think my favorite part of this day though was the treat of seeing a new animal: a porcupine had come to drink water from the road! Though it wasn’t busy when I was passing, trucks & trailers often come speeding over the hill on the highway. So I pulled off the road and got my shovel to gently nudge her back into the brush. Once we were both safely off the road I took photos, but by this point she was a little disgruntled and had raised her quills at me. Don’t worry, I wasn’t close enough to get poked! 😉

Grumpy porcupine

Grumpy porcupine butt

Where do the seeds go?

My purpose in central Oregon over the summer was to collect seed. Specifically, as much seed as possible from species that have never been collected before. I needed a minimum of 10,000 seeds for the seed bank, and a surplus of 30,000+ seeds for restoration projects across the district. Our district database has 255 species that have already been collected, so those 255 species were off limits – I had to find something else to collect.

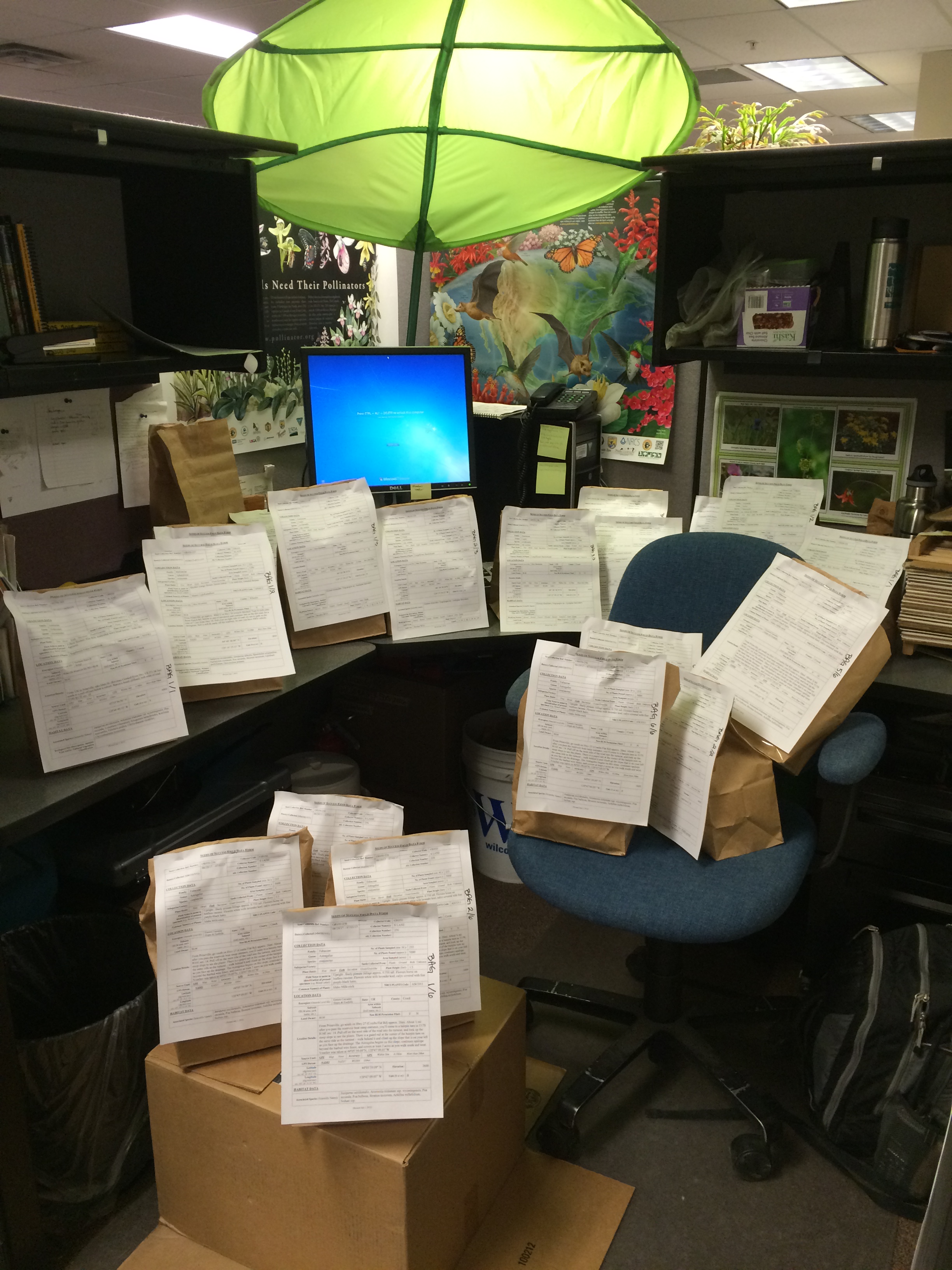

Within a few months of starting my seed collection mission, I had 10 new species in the bag (literally). But all that seed takes up space, and my cubicle was starting to get a little cramped.

Mapping, monitoring, and collecting 50,000+ seeds for a single species: 40 work hours.

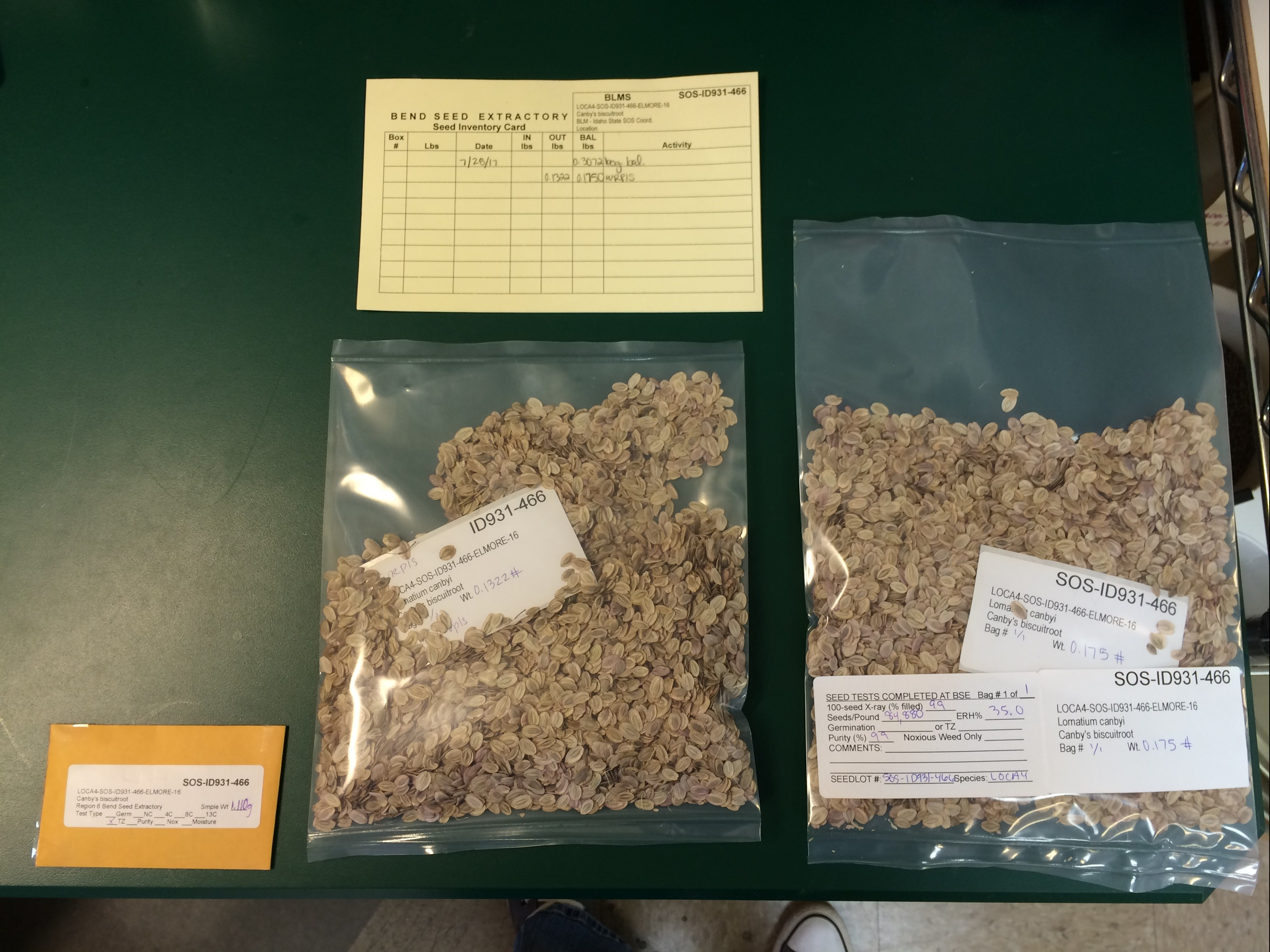

So, what do you do with all that seed? It has to get cleaned, sorted, tested for viability, packaged, and stored properly so it doesn’t get contaminated or expire. Enter: The Bend Seed Extractory!

The Bend Seed Extractory is a facility owned and operated by the US Forest Service in Bend, OR. They receive, catalog, clean, test, and store all the seed that we Conservation & Land Management Interns collect and send to them. The facility houses equipment designed and built over the years by Forest Service engineers, as well as specialty equipment crafted in Denmark specifically for seed cleaning. On my first trip to the extractory I got a tour from Sarah Garvin, Assistant Manager and former Conservation & Land Management Intern.

Custom equipment built expressly for seed cleaning: decades of work by ingenious engineers

Whenever we ship seed to Bend, they receive the shipment into a catalog system like a library. Each collection is identified by the unique code and collection number for the sending office.

One week’s worth of seed shipments from across the US: I estimate 4,500 work hours

I got to see boxes of a yucca species shipped from the crew in Nevada – good work, Nevada team! Your 70 lb boxes of seed were impressive!!

- Pods of Yucca seed, fresh from the field

- 70 lbs!! I admire whoever had to carry that…

Next begins the time-consuming process of figuring out how to clean all the seed. There is no set protocol for a given species because different methods of collection create different challenges for cleaning. For example: a grass seed that arrives still attached to the stem is a different process than grass seed that was stripped clean off the stem.

The seed techs at the extractory know what each piece of machinery is capable of, and what technique it is best used for. They look at each collection like a puzzle, and develop a cleaning method for each and every collection that comes through the warehouse. It might be as simple as sifting the seed through a screen, or using a variety of machines in succession to separate stems, chaff, damaged seed, and good seed.

- Pine seeds separated from cone scales by hand

- This machine has a vacuum hose to remove dust and chaff

- This conveyer belt has multiple types of screens to separate different waste materials at different stages

My favorite machine was the gravity table. The table can be adjusted at an angle so that the heavy seeds will roll faster down the steeper slope, while the lighter chaff and poor-quality seed runs down the flatter part into a waste bin.

- Gravity table for separating seed

- Seed coming down the line: the heavy black seed rolls to the back, while the lighter chaff stays closer to the front

Once the seed has gone through a basic cleaning, it’s time to see what sort of quality you get. The seed gets an x-ray to determine whether the embryo inside is fully formed, or if they were duds. Sometimes a seed can look right on the outside, but their insides haven’t developed properly.

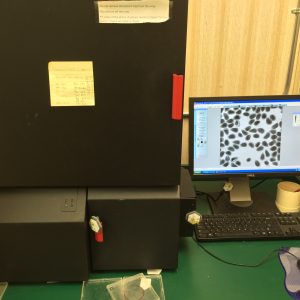

- The black box is the X-ray machine – the seeds go inside on a dish

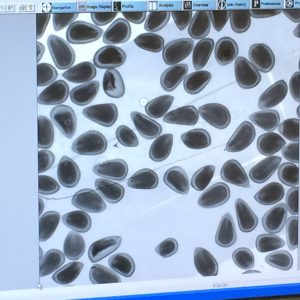

- The X-ray results are viewed on the monitor. Dark seed is good! There are a couple seeds that look like a bubbles that didn’t develop properly.

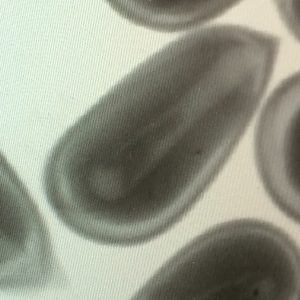

- This is a pine seed. Inside you can see the embryo – the light rod with the Y shape at one end are the cotyledons! This tree is ready to grow 🙂

Depending on how the seed looks, it might go back out for another separation cleaning to filter off poor-quality seed. Again, gravity is our friend. The gravity table shown below is much more sensitive, and has the ability to separate out seed into as many as 5 qualities. This means that you can be sure the heaviest seed is the highest quality, and you can then examine the other assortments for their quality and discard the poor-quality seed.

This gravity table will sort seed with a fine sensitivity. It’s great for very tiny seeds, or seeds of mixed quality.

Once quality is under control, the seed goes for a final round of fine-cleaning before packaging. The second cleaning, or “finishing” phase, is to ensure that the vast majority of content is seed and only seed. This eliminates the fine dust, chaff, and damaged seed from the seed lot. The machines in this step are similar to the ones in the initial cleaning, except smaller and more sensitive.

This machine uses an air column to blow fine dust and chaff up into a collection bin while the polished seed falls to the bottom into a collection container.

- Clean, viable seed, waiting for packaging.

- This much clean, live seed from field to bucket: approx. 100 work hours

Finally, the seed is ready to be packaged! It’s stored at low humidity and 100 seeds are counted out by hand to determine the number of seeds per ounce. Any remaining plant material is picked out by hand to ensure no inert weight is included in the seed lot. By hand, people, no more machines.

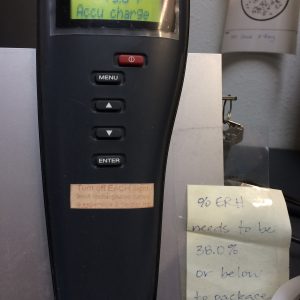

- A relative humidity monitor lets you know if it’s a good day to package seed. Max humidity is 38%, today it reads 37.4%!

- Weighing and packaging a seed lot: approx. 2 work hours

Now is the moment when our precious seed is divided into its three final packages: one sample packet goes to Oregon State University for confirmation of the pure live seed count, one packet of 10,000 seed goes to the Seeds of Success conservation bank, and the remainder is stored in the Bend Seed Extractory refrigeration unit until a field office requests the seed for restoration projects.

Remember all the bags in my office? Hopefully this is what each one will look like after the crew at the extractory gets done with them:

Saving the seeds: priceless.

Tips for Seeds of Success interns.

From collecting seeds and touring a conservation plant facility to monitoring endemic plant species and eradicating weeds, this summer I really feel like Captain Planet’s right hand woman! This is my second season with Chicago Botanic Gardens and you’ve read a lot about my experience here, on the CLM blog. As I wrap up the season, I’d like to take a few moments to give some advice to incoming Seeds of Success interns.

The key to a successful season is timing! Key to life though right?! Timing is crucial because there are some species that take longer to mature and some that take less; the trick is to catch them when they are ripe and ready but not overly ready and have fallen off the plant because then it’s harder, nearly impossible, to collect enough seed. Varying seed maturation is good because if all plants seeded at the same time, we would need to plan a lot more in advance and we’d need a lot more people collecting, decreasing our chances of making big collections. The bad thing is that you need to figure out when the best time is to collect from the desired species and a lot of time there isn’t much information available on those details. Even if there were more information, external factors like weather and pollinator influence play a major role on the progress of seeds from one site to the next. Some species have a large widow of time that they will produce seed, while others will only produce seed for small periodic pockets of time. The key is to closely monitor how fast the plant is maturing and be there at the right time. Some species, like Pseudoroegneria spicata, just don’t have good seed seasons or the window for seed is so short that we never saw enough seed to collect from any of our abundant populations. Some species like Bouteloua gracilis, will produce seed at the same time for the same grass bundle but vary in maturity from grass to grass. That results in shoots of grass that are still in flower while others hold mature seed that is ready for collection. Some species vary in maturity within the same plant like Cleome does; One seed pod was green and under ripe while the pods on the flower next it were fully mature and on the verge of falling off the pod. For collections like those, we went through the same site twice and collected seeds where we could, always making sure not to collect more than 20 percent of the total population of course. Just as important as timing are patience, persistence and mindfulness. Throughout this season I’ve learned that if one of these actions is missing, success falls down to bare bones zero, and your project is bound to become Seeds of Failure! Don’t let that happen to you!

As Scientist, we all know how important it is to keep and regularly update a journal in order to have a record collection of research and findings. SOS definitely requires the constant use of a journal to keep all field data in order. I forgot to write a couple of times and had trouble figuring out what was found or collected if I didn’t document it. It takes less time to sit with my journal for a couple of minutes a day than to spend a whole day trying to figure out what, when and where something happened so just do it.

When in doubt, head to a scenic site! Sometimes we didn’t have a clue where a plant would be, the only lead being the seed zone boundaries! When that was the case, we would go to coordinates that seemed scenic or had some type of attraction that made us want to go there. About 80 percent of the time we would find the species there and/or another plant on our target species list and to top that off, we’d have s killer view for out lunchtime break, win-win!

I’ve been pressing plants since my ethnobotany course as an undergrad student but this season I’ve pressed more plants than ever before. Patience really comes in handy here when you’re working with species that have long and fibrous roots! Sometimes there is more life underground than above! Good luck fitting it all mess in standard press size. I found that roots snap more easily than bend and I snapped a couple of them but a snapped press specimen is better than no pressed specimen right?! It’s nice to know that the pressed plants will be preserved at various institutions including the Smithsonian. I can’t imagine they update their herbarium display very often (or if they even have a display) so you probably won’t find our samples there but either way it’s nice to know that my botanical contributions will be preserved in time.

This season, the Vernal Field Office has made a total of 29 collections consisting of 13 different species, most of which were sent to Bend, OR for cleaning and further processing. Smaller collections and requests were shipped to the appropriate organizations. I started the season a little late so I can’t take credit for contributing to all of those collections, but contributing to most of them is still a great accomplishment. We’ve also compiled a list of at least 15 collection sites for next year’s CLM interns at the Vernal Field Office, you could thank us later J.

Although I completely understand the goals of SOS, there seems to be data lacking support of successful rehabilitation sites from recent SOS collections. We have clear data, maps, and protocols so I’d imagine that it’d be easy to implement follow up protocols on the effect that native seeds are having. As far as I know, there isn’t much published or researched on the aftermath of SOS collections. If there were a clear outline of the benefits of seeding native, then native plants may have greater success being grown in their native land. Many people would benefit from this information for example, people with grazing permits would have a greater incentive to seed native if there were a list of benefits, even if it were a little more expensive. Data could also motivate future projects to replace all non-native plants with native ones (perfect world scenario, I know). I’d also find it interesting to investigate how sites that we collect from are affected by our collections. There seems to be loads of energy used on the collection side of this project but it seems just as important to investigate how we are affecting areas we are collecting from and continually support the fact that SOS is making a positive impact by attaching positive fool proof results and thorough analysis to the equation.

I hope that some interns will find these short tips useful out in the field. Aside from gaining more navigational and data collecting experience, this internship has also helped me gain confidence in this vast field of Botany and I hope you have a similar experience. Earth depends on the continual brainstorming of conservation tactics and techniques in order to preserve the bits it has to offer, I’m grateful I have the capacity to contribute towards its protection. Botany is a lifelong continually changing subject and I’m privileged to contribute my understanding of it in efforts of protecting and maximally benefiting from the study of plants.

Botany Rules! Boys drool (JK! Except for Trump the Frump he definitely drools!!!)!!

Salud,

Vee

And That’s a Wrap

A couple of weeks ago, one of our bosses stopped by our desk and told us about a project out near Beatty Creek that he’s working on to assess tree density as justification for instituting thinning/controlled burns. Obviously we jumped at the chance to survey plots out there; we had been out there before and knew that Beatty Creek is beautiful–very steep, but beautiful nonetheless.

We were not disappointed.

Also, my calves hurt.

(I should probably do some stretches)

Beatty Creek area and our data points

It became obvious pretty early on that the area was overstocked with trees– mostly Pinus jeffreyi, which is a high altitude species that competes best on the serpentine soils that other trees seem to shun. One plot had as many as 127 Jeffrey pine larger than 2-inch dbh! Such numbers, as we’ve been told, indicate that the area is overstocked and likely to burn up should a wildfire come through.

Some other exciting things we saw:

A cool giant boulder straight out of the Lion King

A mountain of gravel probably belonging to the rock quarry who shares roads with the BLM

Various dramatic views

Totally majestic.

Acer macrophyllum changing colors

-

Notholithocarpus densiflorus (tanoak), which is a species of evergreen oak (I’m a big fan of evergreen oaks) that we hadn’t seen for a while

Many, many snakes, including a rattlesnake who didn’t seem to appreciate our presence very much

I’d just like to reiterate that my calves hurt. A lot. But it was so worth it.

(Warning: I’m about to be very sappy and poetic–but what can I say, I was an English minor!)

I didn’t know until I came to Oregon that it was possible to find so much beauty in a place. It dozes among the yellow swells of grass savannahs that fuse with cloudless skies. It buries itself in the thick tide of fog rolling over murky evergreen forests. It’s even contained in the lovely pastel-colored mushroom you discovered on a rainy day–you know, the one that your boss told you not to eat. The one that you didn’t eat because it could give you diarrhea and possibly kill you. Unfortunately.

Working with the BLM in Oregon has taught me more than I could have ever hoped. It’s given me a whole set of skills critical to becoming the crazy botanist I aspire to be: the ability to work ArcGIS, the overwhelming urge to identify every strange plant I almost step on, possibly better balance and coordination (I haven’t fallen down a hillside for at least a week), and, above all, a great appreciation for the beauty of nature.

Thank you.

Farewell, Johnny!

Quote

Looking back on the last five months I am astounded at how quickly this internship has gone by. I still don’t think it has fully hit me that today was my last day, and that I will be leaving the beautiful state of Wyoming in a few days. I quickly fell in love with the Wind River Mountain Range, over which I watch the sun set from my back porch every night, and I have really enjoyed my position as a wildlife biology intern. I can honestly say that this internship has taught me the most and I have gained a lot of amazing experiences and skills. Through working with my BLM mentor and doing field work, I feel so much more directed in my career path than when I first started here. I will continue to pursue a career in Wildlife Biology, hopefully with the Federal government or a non-profit.

This internship has also helped me strengthened my data collection and plant and bird identification skills. It has been a challenging but rewarding experience to get to know a completely different ecosystem from what I have spent most of my undergraduate and professional career working in. The sagebrush steppe has very little in common with the tallgrass prairie! I am so glad I took the opportunity to come out to Wyoming, and I am thankful for the connections I have made here.

When I first moved here, it was so strange to be in a place that was so… unpopulated. The culture shock was real for a while, but I think I have really grown to like the small town fee. It has helped me to grow in independence and has made me more comfortable with solitude, something I was not in any way used to before moving out here.

I am especially thankful for my fellow interns, who have made it easier living out here because there is always someone to do things with. The other interns in my office and I have spent a lot of weekends together, hiking, cooking, and going to local concerts. I am happy to have made connections with them as well as the BLM employees in the field office – and lots of memories have been made! My field partner and I have an unknown plethora of field stories, driving down crazy roads, climbing up steep mountains – literally on all fours, and struggling with our GPS when it couldn’t find satellites.

As I end my internship, I look forward to what I have lined up next. In less than a week, I will be starting a new position in Kansas City as an Avian Biology Technician. I believe the work I have done this summer was integral in setting me apart as a candidate for my new position, and I will be taking the skills I have gained with me as I start my new position. I think going into my next job, it will be beneficial to be comfortable with a little isolation. In fact, I expect that being in Kansas City, around so many people and so much development, will be a little overwhelming.

I ended my internship today the same way I started it – hiking in a canyon area about 45 minutes outside of town named “Johnny Behind the Rocks”, looking for raptor nests and habitat, and still somehow having difficulty breathing on the steep inclines – I really should do more cardio! So today, I said my official goodbye to “Johnny” (referring to the waterfall in the canyon). It has been a great adventure, I leave you with a few photos from these last two weeks. Farewell friends!

“Those who dwell among the beauties and mysteries of the earth are never alone or weary of life.”

-Rachel Carson

Me and two other interns on a day hiking trip to “Johnny”.

The One, The Only, Johnny Behind the Rocks. You know its isolating when you start making friends with waterfalls.

View of the Wind River Mountain Range from South Pass, Wyoming.

My field partner and I on one of our last field day hikes in JBR

On the way to a last visit to the Grand Tetons. Gonna miss being only a few hours away!!

Saying goodbye to the Gem State

Today is my last day at the Shoshone Field Office and it is feeling really bittersweet! I am excited to see what life holds for me next, but looking back, I am beyond pleased with how my internship went. One of my favorite things about this position was the diversity of tasks my boss, Joanna, let us explore; With monarch tagging, bumble bee surveying and bat monitoring with Idaho Fish and Game, electrofishing with USGS, rare plant monitoring with the Idaho Natural Heritage Program, and cultural clearances and cave surveying with other teams in our office, it has been a whirlwind! It was great getting to not only work in other areas of ecology that I have not been exposed to, but also work with other agencies.

Of course not every day can be as exciting, we often helped with more mundane tasks, such as GPS’ing fences and accessing range improvements. These days often involved driving through BLM land for hours on end. However, these days proved to be some of the most valuable in my eyes! Spending nearly entire days in a truck with the same three people can really bond you together like nothing else. We often were at our silliest, leading to funny stories and great memories. The people I have met here have been amazing and I truly feel like I have made life long friends.

Elk skeleton – working in the desert you find so many bones and sheds!

Another great thing about Idaho is how jawdroppingly gorgeous it is! Most of my money ended up going towards gas to explore all of the beautiful sights and I have no regrets. The last five months has given me a chance to explore not only Idaho, but Utah and Oregon as well! These weekend trips have been spent with other CLM interns and has provided me with so many fun and unique memories. I was also only four hours away from Yellowstone National Park, which gave my friends and family back home a great incentive to come and visit!

City of Rocks! One of my favorite places in Idaho!

Uinta-Wasatch-Cache National Forest in Logan, Utah! Coming from Florida, I was so excited to see fall colors!!

Signing off from Shoshone,

Barbara

Goodbye Reno, NV

This internship has challenged me in so many ways- in ways that I anticipated and some that I didn’t expect at all. These past five months have been full of new experiences. I moved to a new state that I had never even seen before, I lived with someone I had never met before and worked in an environment completely alien to me. I thought those things would be the monumental challenges. I was wrong. The considerable test that I wasn’t prepared for was developing myself as a person. Over the last five months, I have not only grown immensely in my professionally but also personally.

In my experience, one of the hardest thing was to be in the middle of the wilderness at night, with no cell service, in my own tent with my thoughts. It used to scare me to not be in constant contact with everyone. Now, I would recommend it to anyone and everyone. There is a certain bliss to falling asleep and waking up off the grid. I have seen mountains, cliffs, streams and animals that most people never get to see and I got to get paid for it.

Patience was key during this internship. When getting ready for a hitch out in the field, it is impossibly easy to feel absolutely prepared for anything and everything. That is until you don’t pack the right gear for the weather, you don’t feel like eating peanut butter and jelly sandwiches for the 4th day in a row, or when you get your truck stuck in mud. There are always set backs and things that you couldn’t prepare for. I have learned to be patient and to not get frustrated when things don’t go perfectly smooth.

Professionally, this internship gave me more experience than I could have ever hoped for. I wasn’t exactly sure what to expect coming in to this, but I have been able to add countless skills to my resume. There were skills that I assumed I would gain such as the opportunity to learn western flora, driving USFS/BLM off-road systems as well as mapping them. What I gained was so much more than that. I was able to learn CPR, Wilderness First Aid, PFC stream assessment and countless more. I have worked in the field, in the office, the library, the local college, the herbarium and out of my truck. I have learned to be adaptable, to be efficient but relaxed and how to be safe under hundreds of conditions.

I am so grateful for this internship and this experience. I feel as though I have gained so much from it and from my mentor. I have the rest of this week and part of the next left and I can’t believe how quickly it flew by. Now time to prepare for my 32 hour road trip back home.

Good luck everyone in your endeavors!

Payton Kraus