Every day in the field is an adventure. I do my best to be prepared, to take precautions, and to not take needless risks. Most of the time I work by myself, so if anything happens I’m on my own to figure out a solution. I have a truck full of supplies and gear, but I’m still just one person – there’s only so much I can do. For example, I can’t pull a truck out of a mud pit by myself.

“Oh, did you get stuck in a mud pit?”

Yes. Yes I did.

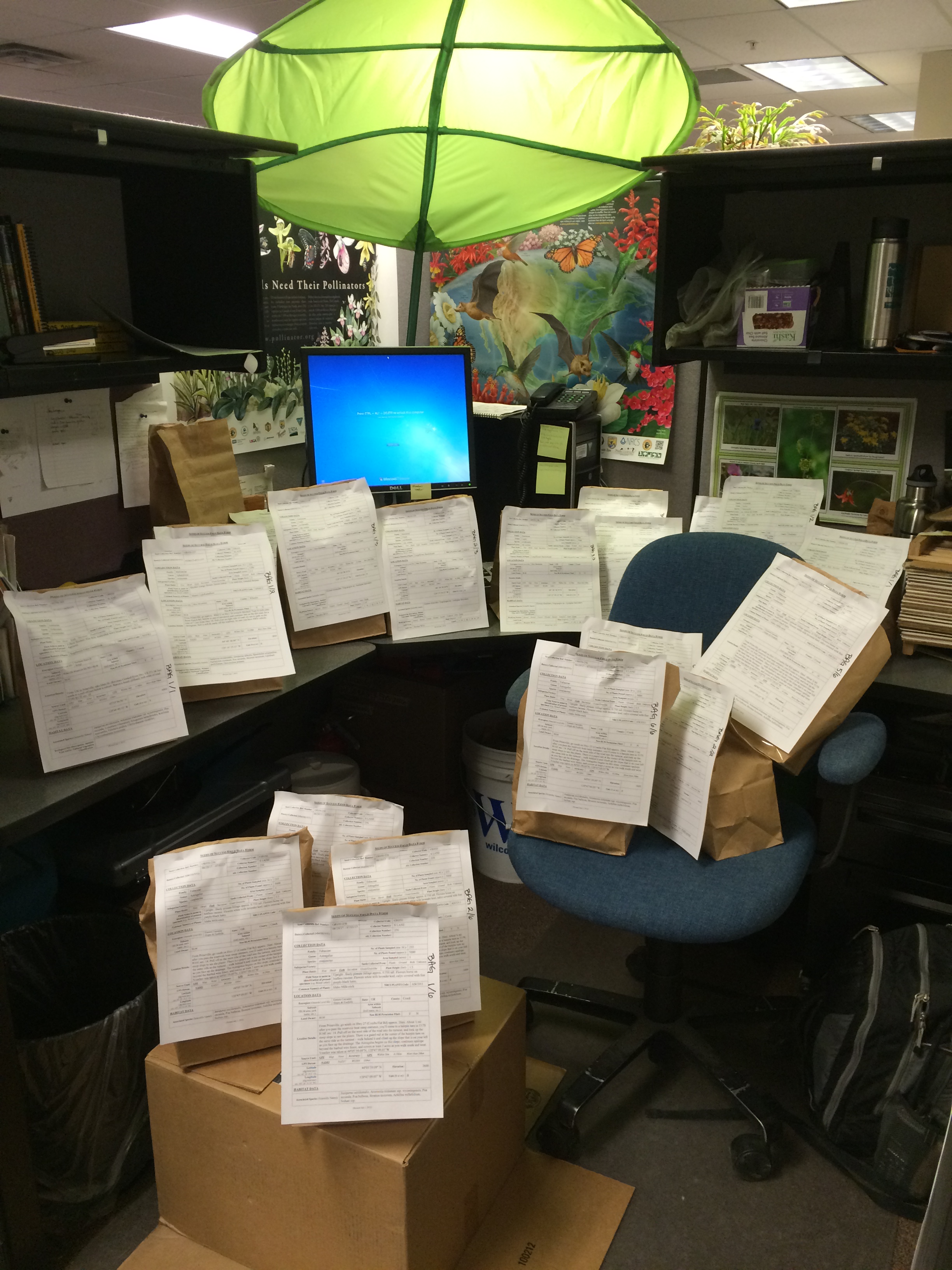

Normally I drive an F350 4×4 with super-duty tires. It’s a big truck, and I’ve skidded it sideways through several long, deep muddy pools on old forest roads with towering Ponderosa Pines crowding in on either side of me. It handles like a boss. As long as one tire was gripping, I’ve been fine. I thought I had mastered mud.

Yay truck!

But I don’t always get to drive the F350. It had to go in the shop for maintenance, so I had to scrounge for an extra truck in the vehicle pool. I got an F150 – it had all-wheel drive, it was cleared for off-road field work; a little closer to the ground, but that’s ok. I didn’t think too hard about taking out to my seed collecting site on Camp Creek.

The thing about the Camp Creek location is that it’s part of a grazing allotment. Grazing allotments have well pumps to shunt water to cattle tanks all over the parcel. The little road that I needed to get on has such a pump, but it leaks. The leak is bad enough that the road is always muddy, and now that the cows are on the pasture it’s just a rutted, trodden wallow.

When I arrived, I walked the wallow & scouted my path: I kept two tires on dry ground & made it through just fine. I found the excess barbed wire the rancher had trimmed off the gate so the cows could access the creek & tossed it in the bed of the truck. I felt so smart: no flat tires on my watch! I flipped into low gear & eased the little truck down the steep bank & across the creek. I was so happy, I’m really getting the hang of this off-roading stuff. I did my site assessment, and made my way back to the main road.

The crossing at Camp Creek. It’s hard to judge by the photo, but the road on both banks is about a 40* incline, and there are some big, pointy rocks hiding in there. The water isn’t too deep, but you have to stay right on the track – there’s exactly enough room for the truck, but not much room for error.

Except this time when I came back, there was a herd of cows in my way. In the hour or two since I had crossed, about 30 cows decided it was time to get a drink, and they were standing around in the mud puddle where I needed to cross.

My path on dry ground is blocked by cows. The bush in the left foreground is growing out of a nick point where the drainage has carved out a deep cleft – can’t really go that way.

Ok, so there’s cows. Hm, and a bull. I don’t really want to get out & charge at the bull – the cows should move if I drive up to them, right? I started forward, trying to politely edge between the cows & the mud. My left tires were sliding into the mud, but that was ok – my right tires were on dry ground. I was doing fine.

But then I wasn’t. One of the cows got jumpy & dodged into my path. Not wanting to hit her (of course), I turned to the side. And slid totally into the mud pit – now no tires were touching dry ground, they just spun in place.

Hey, I can get out of this. I’m not that far in, I’ll just dig it out a bit & reverse it. So, I got out my shovel & started digging. I dug out the wet, sloppy clay full of cow manure. I dug dry earth with clods of dead grass & packed it under the tires as best I could. I was ankle deep in the mud, my feet were sliding around in my boots. The cows thought this most irregular. I continued this exercise for about half an hour.

It’s not every day you see something like this.

I put everything back in the truck & started it up. I put it in reverse & eased the gas, slowly rocking it until the truck moved backward. I moved! Awesome!! I’m going to get out of this mess, I was so proud! Until I slid back toward the corner of the mud pit where the drainage goes underground. The crevices are a few feet deep, and my back tires were sliding towards them. I stopped.

I got back in the truck to think. The novelty of being stuck in the mud had worn off, and I was angry. The cows were increasingly intrigued. Why couldn’t they have found some other water spot? Why did they need to stand around this muddy puddle?!?

You’re not helping, cows.

I stared at the cows. I stared at the sagebrush. I pondered how the indigenous people here peeled the bark off the sagebrush to make sandals. I had an idea: I could use the sagebrush too! I could cut the sagebrush & pack it under the tires & across the mud to get some traction! Ooh, I felt smart again!

I grabbed my pruners and leapt out of the truck, nearly hugging the first bush I tripped over. But, my pruners wouldn’t cut through the tough bark. They twisted and frayed the branches, but the damn stuff just wouldn’t cut. The cows inched closer to see what was so interesting about the sagebrush they stood in all day. One was so close she was breathing in my face. I was furious: I screamed at the pruners, I screamed at the cows. I waved my shirt at them, yelling and stomping after them. First they looked surprised, then they actually started, a little taken aback. I ran all around the truck like a manic monkey, screaming & jumping & swinging the shovel trying to make the stupid cows leave me alone. They actually turned and ran off a bit, but only when I was running directly at them. I ran at all of them in a big arc, hollering like an idiot. One of them stopped. It turned and gave me a look like it had suddenly become aware of its relative size. I was chasing the bull.

I stood still and stared down the bull, brandishing my shovel at it. He let out a low growl that shouldn’t come from an herbivore. I stood even more still, but glared at him just as intently. He eventually blinked and licked at his hoof. I backed towards the truck & got in the bed. (Sorry I don’t have pictures of this part.)

Standing in the bed of the truck I watched the cows listlessly walk off, kicking up a dust trail as they went off in search of less animated company. The bull followed them. I looked down at the toolbox, and upon opening it I found a hand saw. It was dull and rusty, the tip was broken and bent, but it was better than my pruners. I jumped down & started furiously hacking away at the sagebrush. Just then, a truck rolled along the adjoining main road. As it approached the crossing herd, I waved with both arms. Much to my chagrin the cows turned away from the road back towards me, and the truck passed by without hardly slowing. I kept sawing.

Having seemed to forget that just minutes before I had been charging them with a shovel, the cows gathered around again to watch. The bull seemed to grant me permission to cut sagebrush on my side of the truck, and he entertained himself on the other side. Once again I dug out the tires, wedging the sagebrush as deep as I could under them. I made a little bridge of sagebrush across the mud, hoping that if I could just catch one piece well enough, I’d pull myself out of there.

I tried so hard.

Sagebrush bridge constructed, I once again chased off the cows. I didn’t want them to obstruct what could be my only chance to get out of their most favorite mud puddle in the entire allotment. But, my wheels only spun in place. The sagebrush got mangled a bit and sucked down into the mud, but the tires were so slick by this point they just couldn’t grip anything. I’d been in the same spot now for two hours, self-sufficiency was no longer productive.

“Lane to Dispatch on Grizzly…” The cows wandered off almost single file, the show was over.

The desert was silent. I could hear the wind gusting over a hill, I thought I could hear it turning directions. Sometimes a bird would peep. There weren’t any bugs, just me and the sky and the muddy trickle of the broken well pump running under the truck and into the crevice.

About an hour and a half after getting in touch with Dispatch, a Forest Service crew rolled up in a giant rig with a winch. They affirmed my sagebrush bridge attempt, and affirmed how well I was stuck. One of the crew members kicked the tires.

“There’s your problem right there. Just road tires on this thing.”

With the winch hooked up they pulled me out without any difficulty, and even followed for a stretch to make sure I didn’t have any further problems with the muddy tires.

The next week I returned in my trusty F350 and its super-duty tires. I drove clear over the sagebrush, avoiding the mud altogether. There were no cows that day.

– Stefanie Lane, BLM, Prineville, OR