Greetings world,

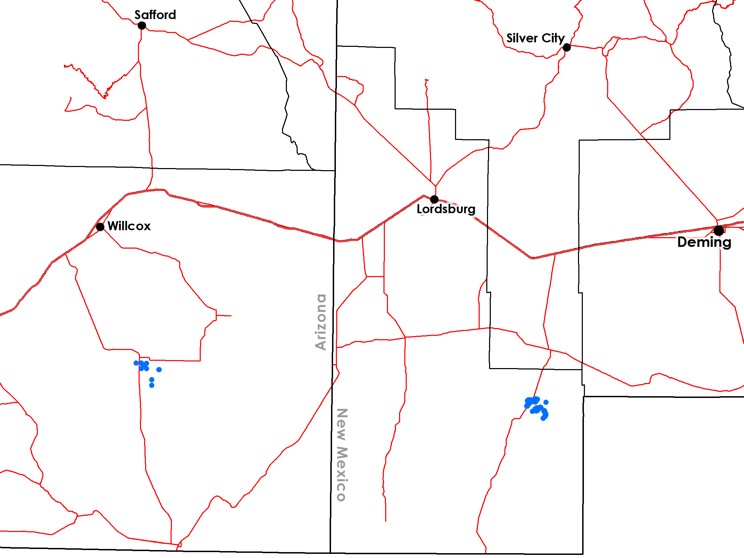

As of 2008 there were only two known populations of Pediomelum pentaphyllum, one in southwestern New Mexico and one in southeastern Arizona. Other populations had been reported in the past, but either could not be found in recent surveys or had sufficiently vague localities that no one was really sure where to search. I mentioned one of those vague localities in a previous post here, a Mexican Boundary Survey specimen that was collected in the general vicinity of the Rio Grande somewhere between Doña Ana and Big Bend. It could be in New Mexico, Texas or Chihuahua–good luck! In 2008, Pediomelum pentaphyllum was petitioned for listing under the Endangered Species Act based, in part, on this very limited distribution. Here’s an approximate map of the known populations in 2008:

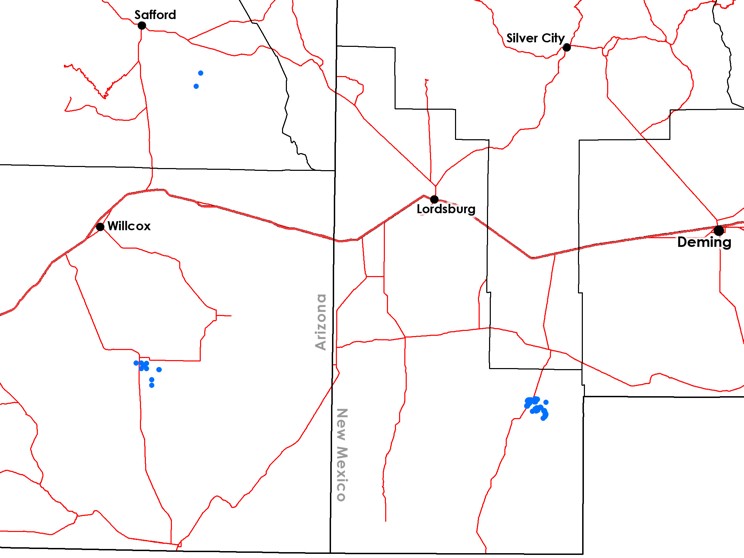

Over the next few years, more searches were made. My first, very brief, work with the BLM was one of these, wandering around for a couple of weeks and finding all kinds of fun plants but no Pediomelum pentaphyllum whatsoever. A couple of botanists in Arizona (Marc Baker and Laura Pavliscak) did succeed in finding a couple of new populations (or one bigger population, depending on how you want to look at it; “population” is essentially an undefined term!), though. So, that puts us up to threeish populations:

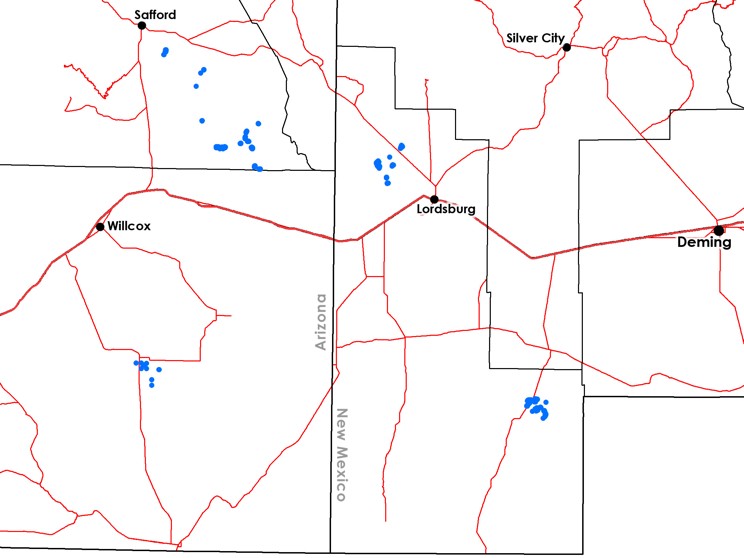

However, this year either conditions were better, the botanists conducting surveys were better, or (most likely) we were just plain lucky! More populations in Arizona and New Mexico were found by myself, Joneen Cockman of the Safford Field Office, and our associated field crews. I don’t know how you might count the number of populations at this point but the gist is there are a fair number of them–and more being found, last I heard from Joneen! Pediomelum pentaphyllum is starting to look a bit less rare:

Just in case you’ve forgotten what Pediomelum pentaphyllum looks like, here are a few more pictures of it:

And here’s what the habitat looks like for several of the new populations. Try spotting the Pediomelum pentaphyllum–there’s at least one in each photo!

I think we’re starting to get a better idea of the habitat Pediomelum pentaphyllum likes. All of the new populations found this year were in loose, sandy soil with Prosopis glandulosa and “other shrubs”. The other shrubs could be Artemisia filifolia, Atriplex canescens, Atriplex polycarpa, Lycium pallidum, or Larrea tridentata–but in any case it’s not just our typical boring mesquite shrubland. Hopefully, as we continue to refine our idea of good Pediomelum pentaphyllum habitat, we’ll be able to keep finding more populations and have a better idea of where it isn’t going to be found as well. I also learned this year that some populations of Pediomelum pentaphyllum are guarded by Crotalus scutulatus:

The other exciting development here is that Nerisyrenia hypercorax, a new species we (Michael Moore, Norm Douglas, Helga Ochoterena, Hilda Flores-Olvera, and I) discovered last year on the west side of the Guadalupe Mountains, has been published in the Journal of the Botanical Research Institute of Texas. There’s also an episode of Plants are Cool, Too! that includes this species. Nerisyrenia hypercorax is a gypsophile, meaning it occurs only on soils high in hydrated calcium sulfate, a.k.a. gypsum. As you may have guessed from my post about Alkali Lakes, gypsum in New Mexico is home to a whole slew of rare plants and makes for excellent botanizing–at least, provided you avoid some of the worst of summer heat, which seems to be amplified on gypseous soils! We keep finding new species on gypsum–Michael Howard, our soon-to-be-retired state botanist, found another new gypsophilic plant (Linum allredii) just a couple years ago. And, of course, I have pictures of Nerisyrenia hypercorax:

And of its habitat: