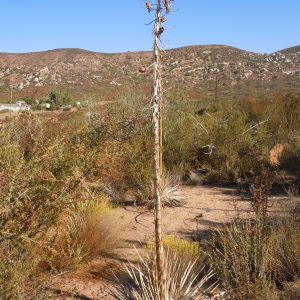

Crawling like a baby on sticks, through sticks, and with sticks in my hair. Branches grab my shoelaces and refuse to let go, trapping me in a maze of manzanita, chamise, and coyote brush so thick it’s difficult to see my friend just six feet away. But today we’re on a mission, and even the new rips in my pants can’t stop me. Finally, the extreme bushwhacking pays off, and I find my prize: a small patch of Layne’s butterweed (Packera layneae), a small and unassuming Federally threatened plant found predominantly in western El Dorado County.

For the past 5 months I’ve been lucky enough to intern with the Pine Hill Preserve (PHP). Eight rare and endangered chaparral plants–including five which are Federally listed!!–rely on the unique mildly acidic red soils created by the underlying gabbro rock. In the face of encroaching suburban sprawl, PHP is a refuge, protecting these special chaparral plants and the unique soil formation on which they rely.

An urban girl by birth and forest lover by experience, I’ll admit to being disappointed on my first visit to PHP. When they said “shrubland” I’d pictured the open sagebrush of central Idaho and was completely unprepared for the dense 7 ft. tall stand before me. It was over 105°F, and the plants were anything but friendly. I spent the first afternoon wishing myself away.

Quickly, however, PHP won me over. The chaparral doesn’t have jaw-dropping mountain vistas or the grand splendor of coastal redwoods, but it does offer a quiet, more dignified beauty to those willing to look beyond it’s rough and often spiney exterior. Hidden among shopping centers and private homes lies a biological wonderland. Over 740 distinct plant species grow here–that’s 10% of California’s total native plant biodiversity in a tiny fraction of the state! Visiting PHP may include a leisurely hike along the interpretative trail, attending a naturalist-led bird & botany tour, or simply enjoying a moment alone along the S. Fork American River.

Quickly, however, PHP won me over. The chaparral doesn’t have jaw-dropping mountain vistas or the grand splendor of coastal redwoods, but it does offer a quiet, more dignified beauty to those willing to look beyond it’s rough and often spiney exterior. Hidden among shopping centers and private homes lies a biological wonderland. Over 740 distinct plant species grow here–that’s 10% of California’s total native plant biodiversity in a tiny fraction of the state! Visiting PHP may include a leisurely hike along the interpretative trail, attending a naturalist-led bird & botany tour, or simply enjoying a moment alone along the S. Fork American River.

Although an ecological hotspot and a recreational area regularly utilized by mountain bikers and birders alike, development threatens El Dorado County’s chaparral. Private homes encompass PHP lands, limiting the BLM’s fuels management options, and neighboring unprotected natural areas are being bulldozed at an alarming rate. While PHP rare plants may thrive on nearby undeveloped privately-owned parcels, without protection like that afforded through purchases with LWCF funds their days may be numbered. Entire species may suffer if more land isn’t protected. For a species like Pine Hill Flannelbush (Fremontodendron californicum ssp. decumbens) with only ~100 plants worldwide, losing even a handful of individuals to private development may dramatically reduce the entire species’ genetic diversity with detrimental effects.

Growing up in urban Ohio, nature was the occasional trip to the “wilds” of a regional forest for fishing or hiking. Although my definition has since expanded to include the mountains of Denali and redwood forests, nothing can compete with the chaparral’s hidden gems. Despite PHP’s navigation challenges and my co-worker’s bold statement, I proudly admit that I LOVE the chaparral, most days anyway.

Growing up in urban Ohio, nature was the occasional trip to the “wilds” of a regional forest for fishing or hiking. Although my definition has since expanded to include the mountains of Denali and redwood forests, nothing can compete with the chaparral’s hidden gems. Despite PHP’s navigation challenges and my co-worker’s bold statement, I proudly admit that I LOVE the chaparral, most days anyway.

Over and out. Sophia Weinmann

CLM Intern: El Dorado Hills, CA

Quickly, however, PHP won me over. The chaparral doesn’t have jaw-dropping mountain vistas or the grand splendor of coastal redwoods, but it does offer a quiet, more dignified beauty to those willing to look beyond it’s rough and often spiney exterior. Hidden among shopping centers and private homes lies a biological wonderland. Over 740 distinct plant species grow here–that’s 10% of California’s total native plant biodiversity in a tiny fraction of the state! Visiting PHP may include a leisurely hike along the interpretative trail, attending a naturalist-led bird & botany tour, or simply enjoying a moment alone along the S. Fork American River.

Quickly, however, PHP won me over. The chaparral doesn’t have jaw-dropping mountain vistas or the grand splendor of coastal redwoods, but it does offer a quiet, more dignified beauty to those willing to look beyond it’s rough and often spiney exterior. Hidden among shopping centers and private homes lies a biological wonderland. Over 740 distinct plant species grow here–that’s 10% of California’s total native plant biodiversity in a tiny fraction of the state! Visiting PHP may include a leisurely hike along the interpretative trail, attending a naturalist-led bird & botany tour, or simply enjoying a moment alone along the S. Fork American River.