We kicked off the beginning of this month with a visit to the Botanic Garden to see their array of native and ornamental plants alike. There, we got to speak with their land managers, researchers, and horticulturists; as well as touring their greenhouse facilities, bonsai displays, and laboratory spaces.

One of the most memorable moments was an opportunity to view the plant with one of the largest flowers in the world — the Titan Arum (Amorphophallus titanum). A single leaf from this species is the size of a small tree, and it’s inflorescence smells of rotting flesh to attract fly & beetle pollinators.

At home, Courtney and I have been busy raising pollinators of our own for the past month. Hatching from an egg the size of a pinhead, Monarch Butterfly (Danaus plexippus) caterpillars quickly grow to impressive sizes.

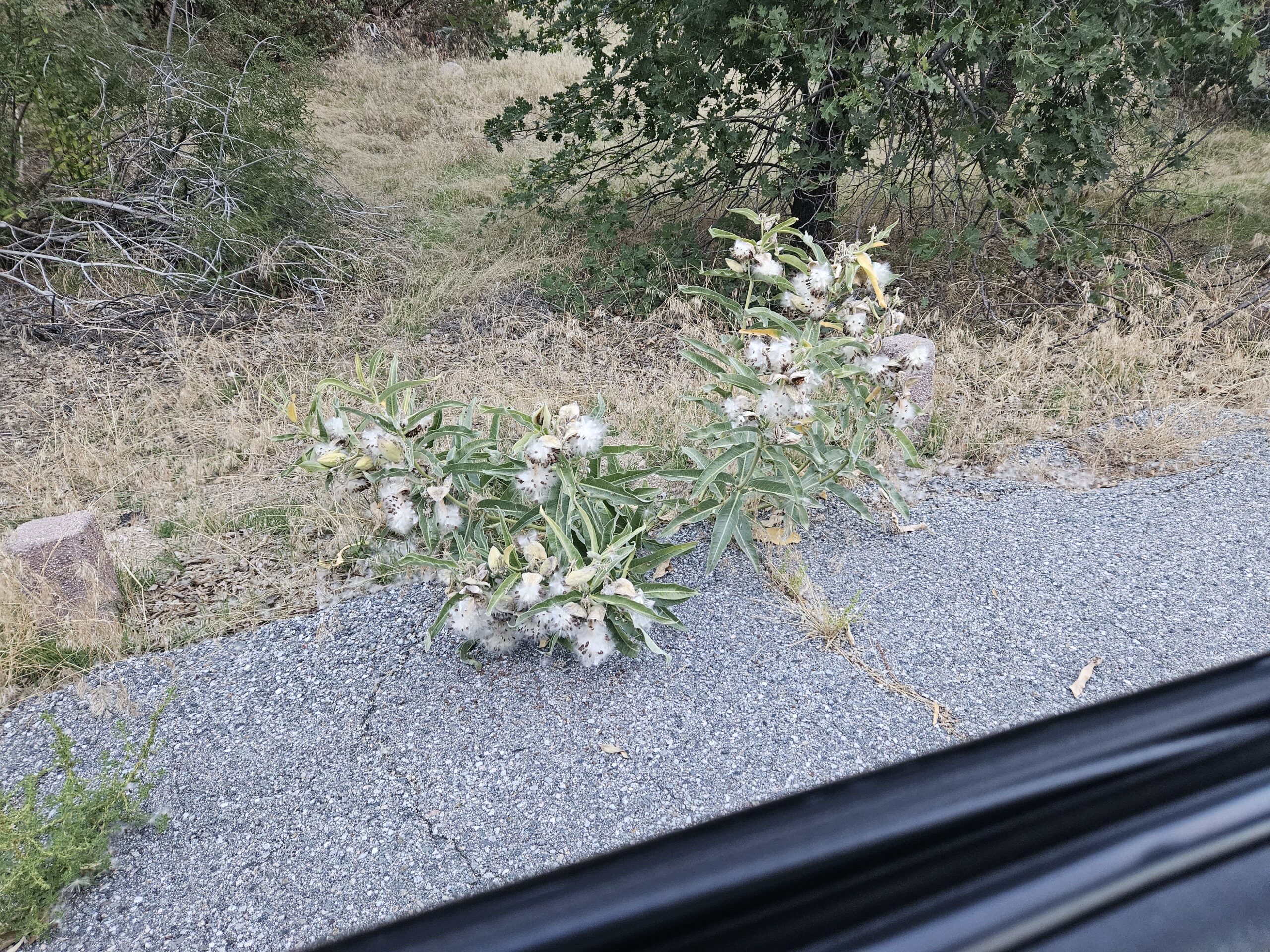

And after seeming to eat Milkweed (Asclepias spp.) leaves just as fast as you’re feeding them, they finally form their chrysalises before hatching as butterflies. These Monarchs will soon fly southbound to Mexico to roost in Oyamel Fir (Abies religiosa) trees during the winter.

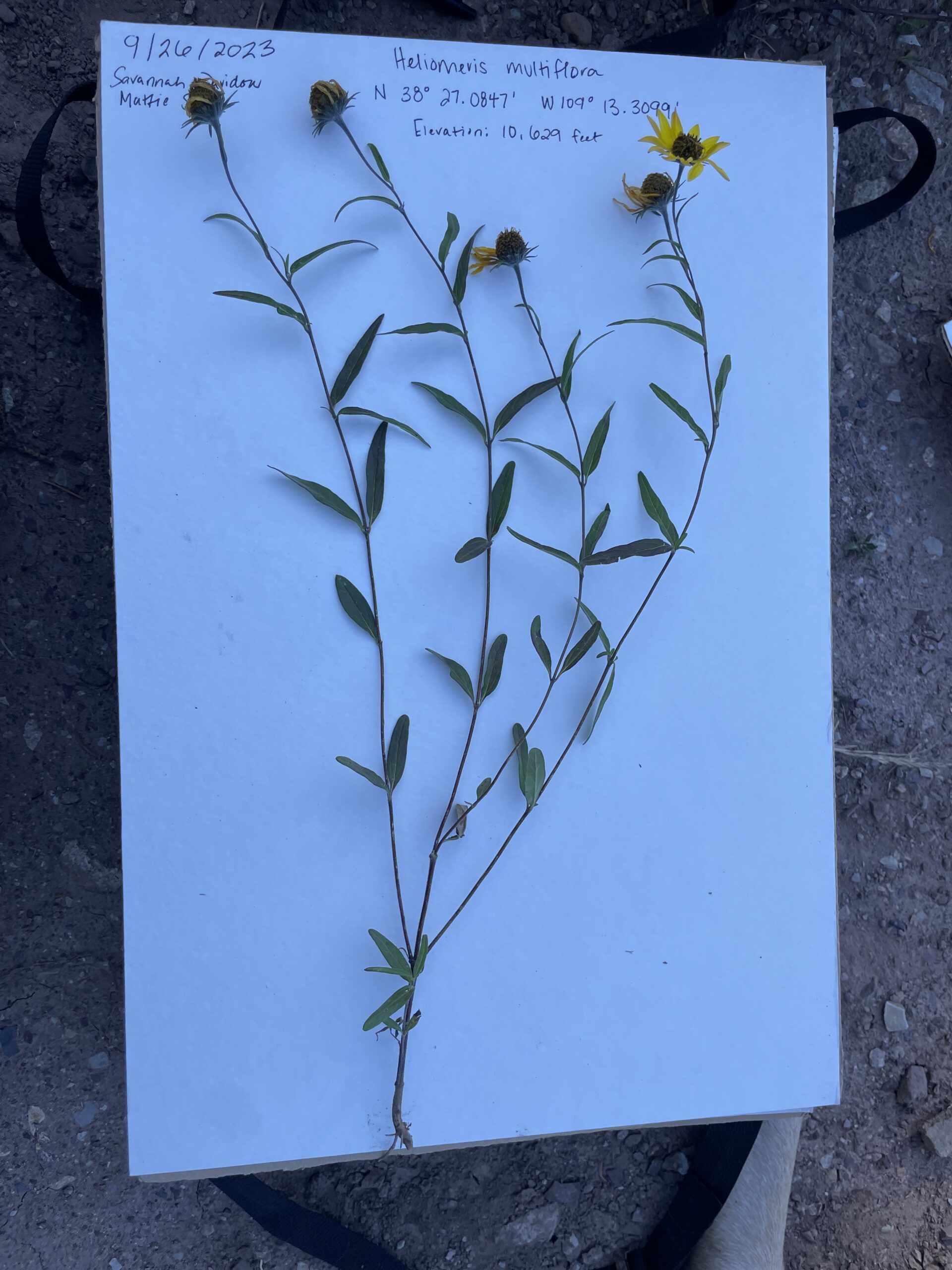

The month hasn’t been all play and no work, however. Seed collection is in full-swing back at Midewin, as indicated by strange calluses I’ve found on my fingers from hand-pulling and cleaning seed. We’ve also learned how to operate the mechanical seed cleaning equipment to process seed in bulk.

Many of our afternoons have been filled with the satisfying pulls of Sideoats Grama (Bouteloua curtipendula) or pops from Prairie Coreopsis (Coreopsis palmata). Seed collection is also a great time to explore some of your favorite places on the prairie: be it the view from the top of Sand Ridge, Lobelia Meadows and the blooms of its namesake, or the scattered rock pools at Exxon.

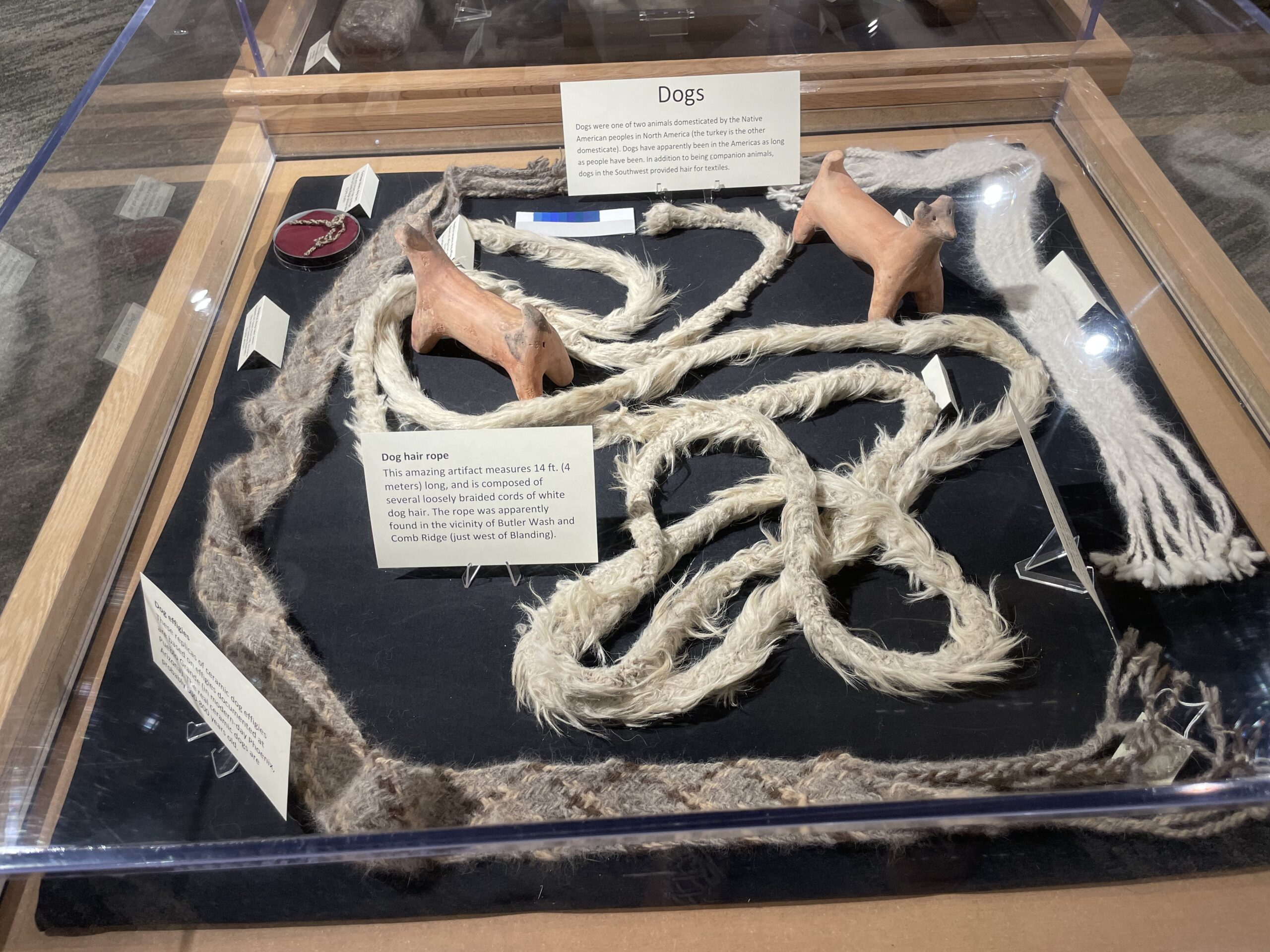

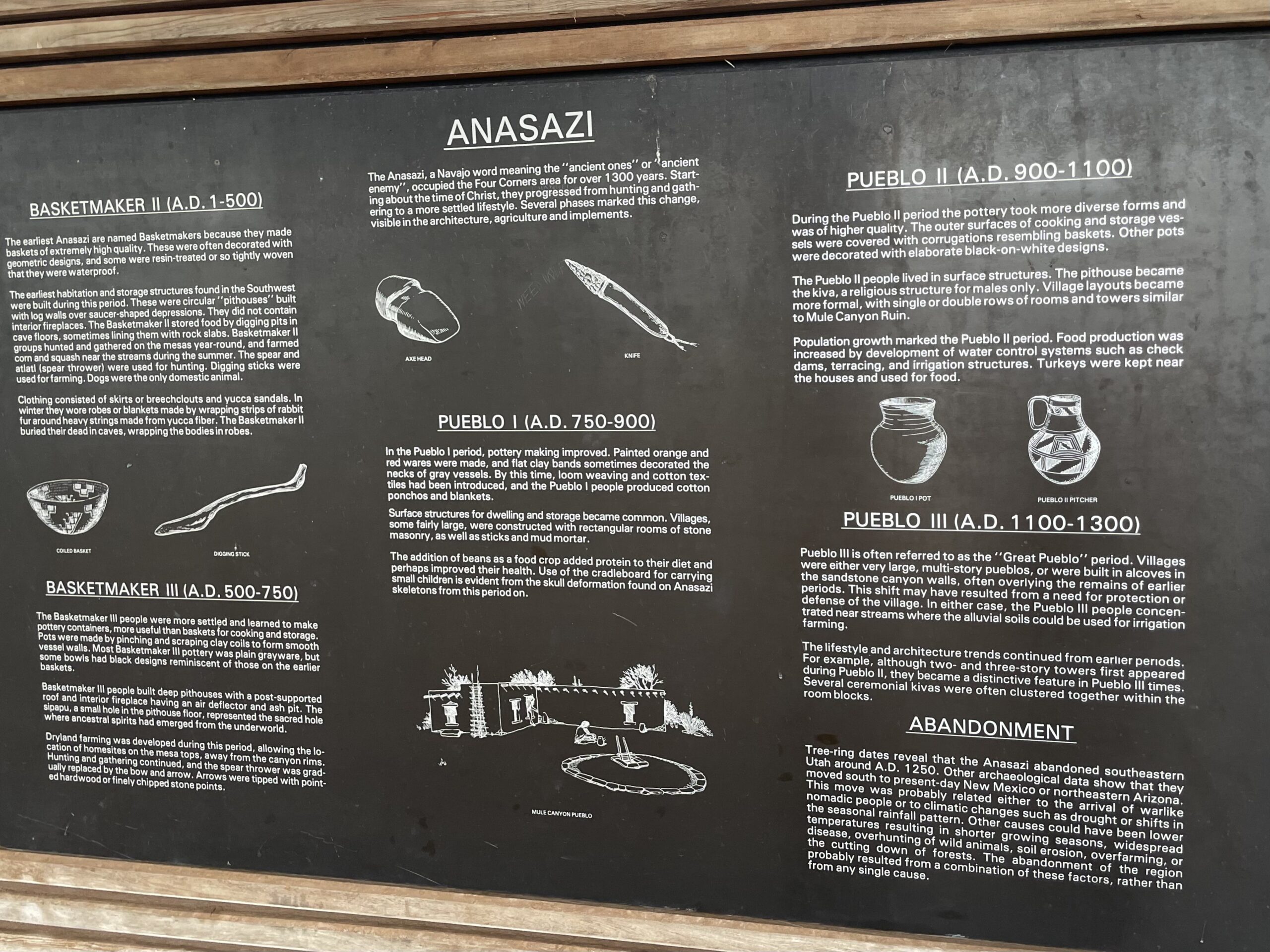

Whether passing bunker-fields from the old Joliet Arsenal or overgrown hedgerows of Osage Orange (Maclura pomifera) from abandoned homesteads, we are constantly reminded that the prairie is a landscape shaped by human interference. Not only in its destruction by the plow, but also its early maintenance through fires set by local Native American people.

Illinois’ long history of land-use offers a unique perspective on ecological stewardship. Very little remnant prairie still exists in the state today, and with little-to-no native seed bank remaining, most restorations must start from complete scratch. But with the seed we’ve collected throughout the summer, we’re proud to be doing our part in returning native habitat to Midewin.

Dade Bradley

Midewin National Tallgrass Prairie