Greetings, World!

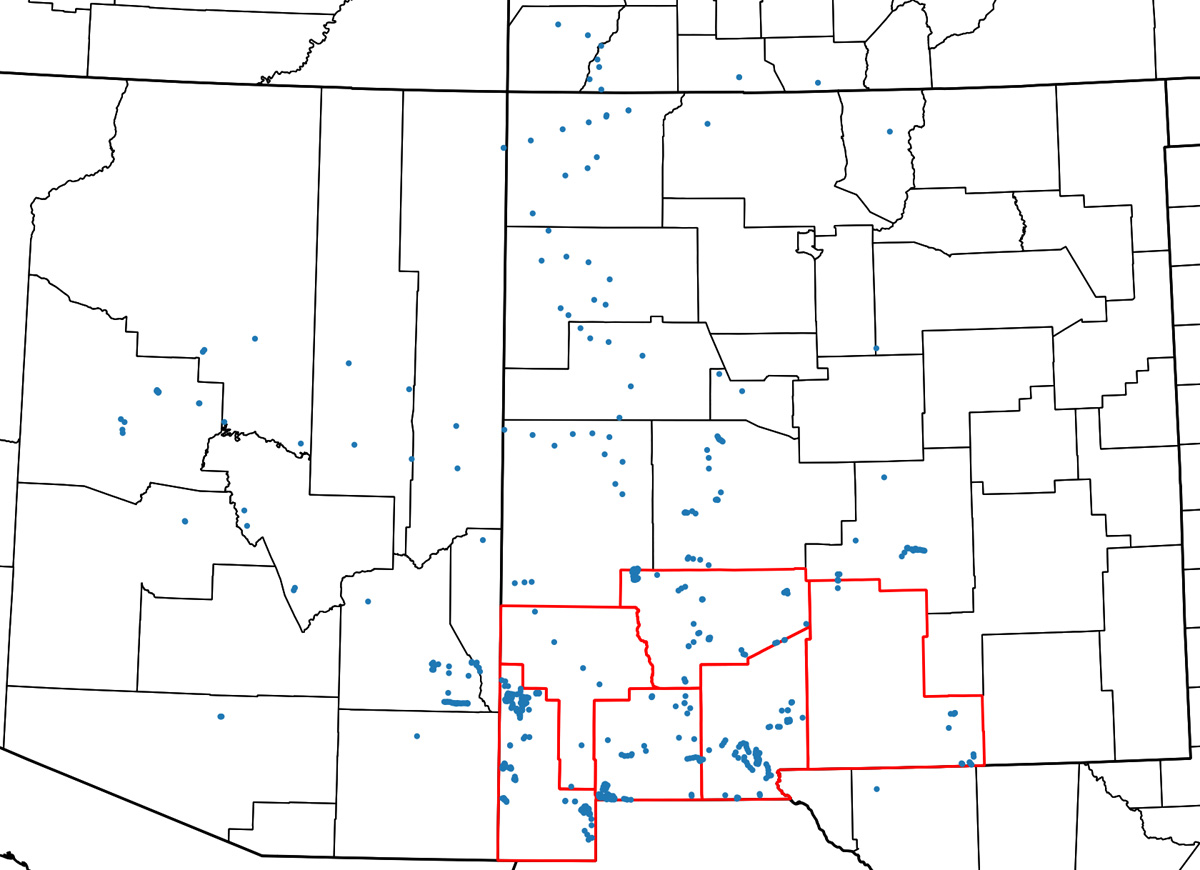

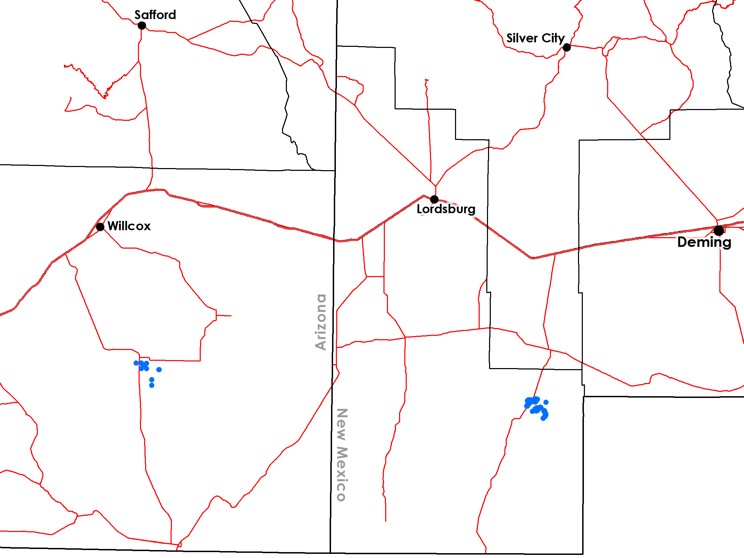

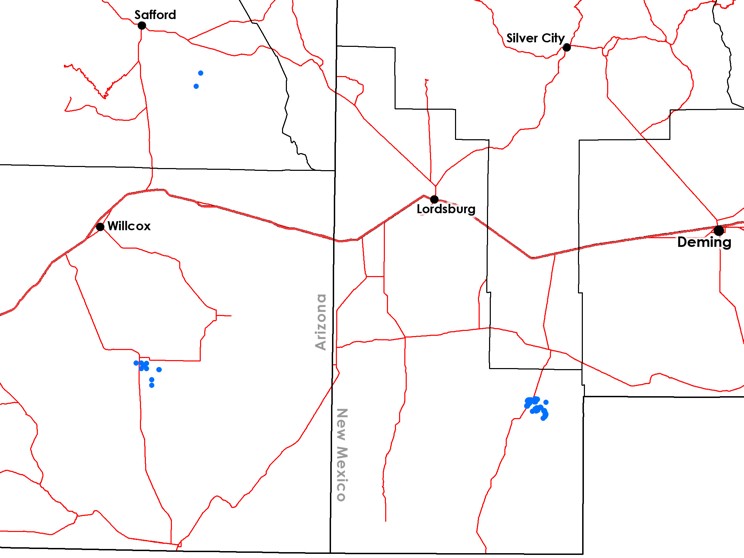

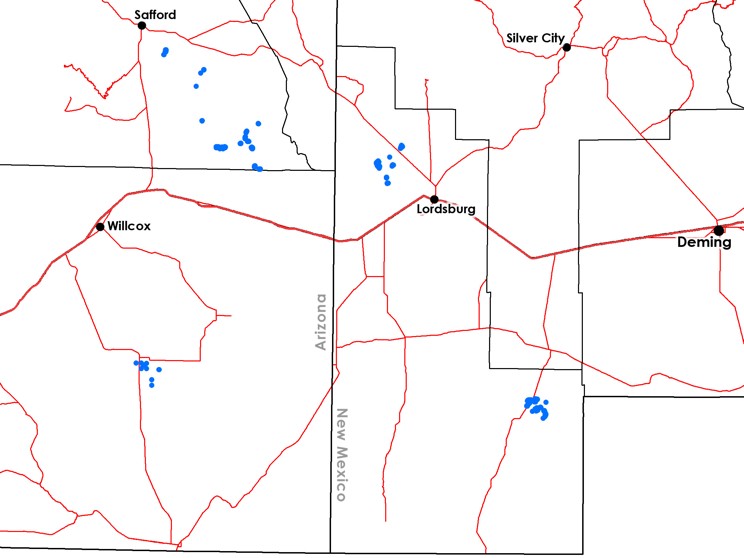

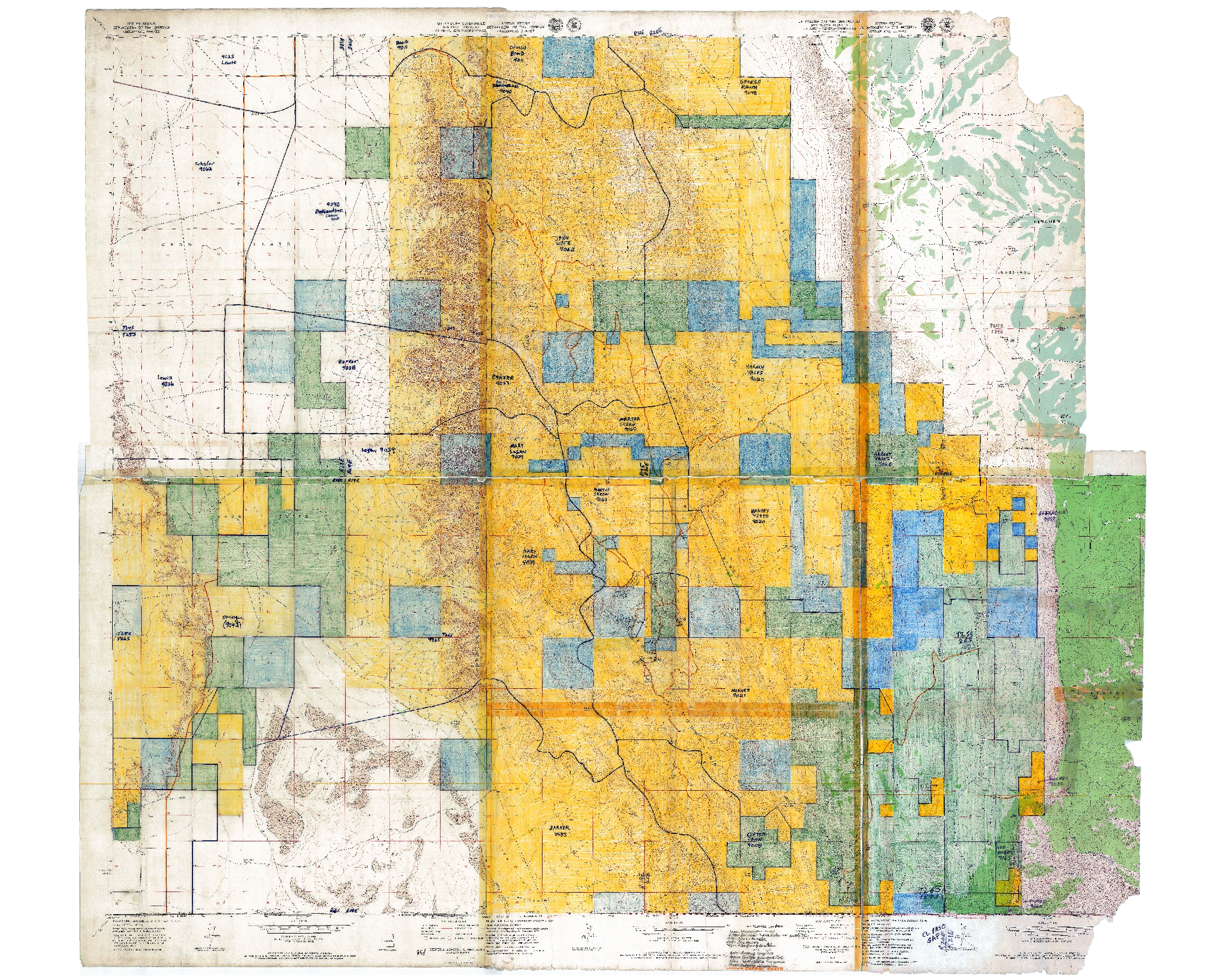

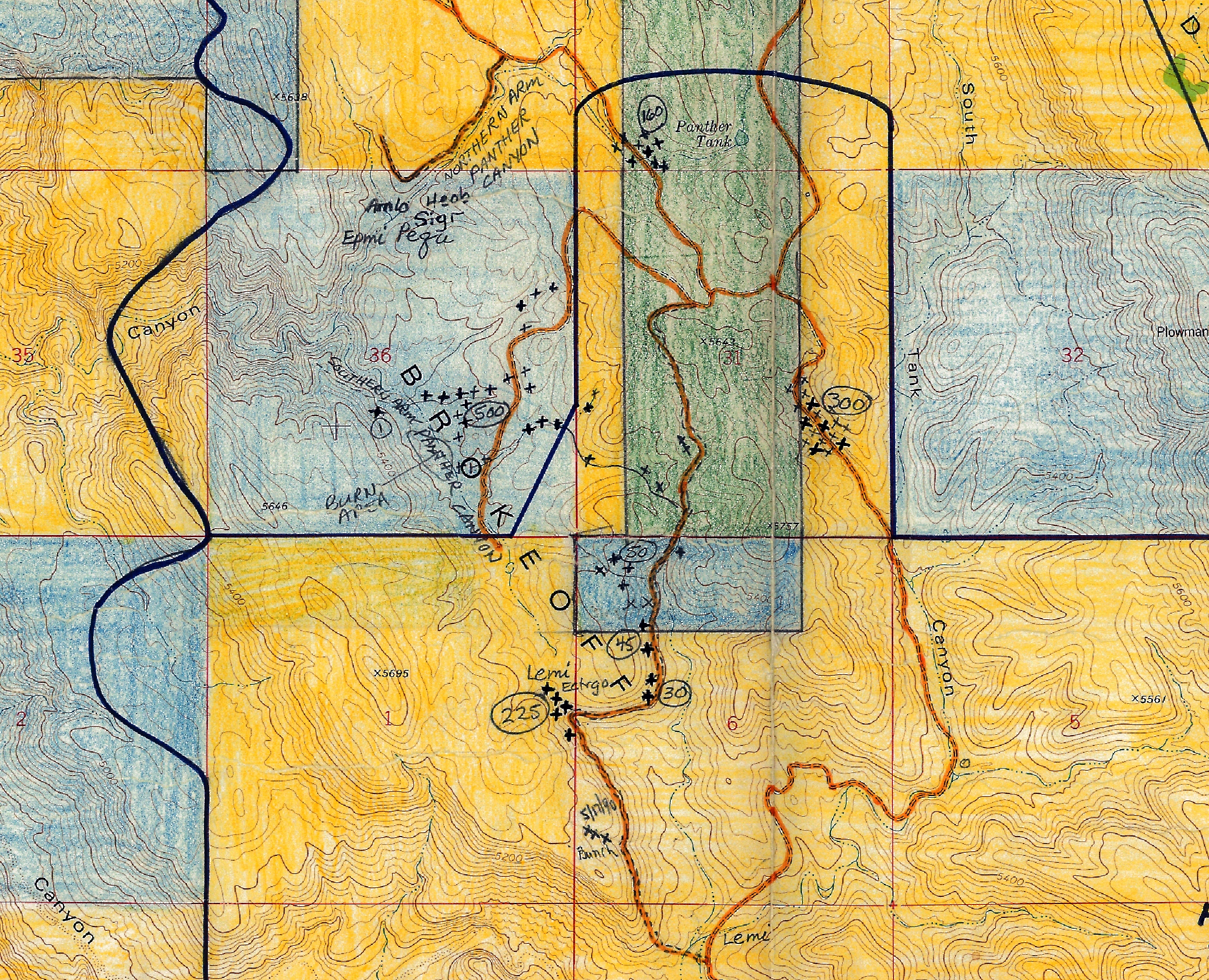

One of the basic challenges of any land management agency is figuring out what’s out there. The BLM Las Cruces District manages 5.4 million acres of public land. Although I do my best to get outside and visit as much of it as I can, that’s a lot of land to cover. There are many GIS layers we can use to get around this problem and understand what’s happening on the landscape in areas we can’t personally visit and experience, but one of the most informative is aerial imagery. Trying to understand aerial imagery is also, in my opinion, just about the most challenging and entertaining thing you can do with maps! My basic process in training myself to understand aerial imagery is to stare at maps for a while, guess what I’m looking at, and then go outside and see if I’m correct. Sometimes this is part of my job, sometimes this is just what I do for fun. Once you get a good sense of the relative scale of the different shrubs, what grasses to expect in what context, and the like, you can get a surprising amount of information from aerial imagery and, in reference to Stillman‘s recent post on this blog, sometimes you can even make out the stems of ocotillo from aerial imagery! Of course, there are still many things you can’t understand without being out on the ground.

There are also various programs that implement basically the same approach in an automated computational framework. LANDFIRE, for instance, produces vegetation maps by taking vegetation plot data and then running GIS wizardry to interpolate and classify all of the areas between the plots. That’s useful, but not nearly as much fun. So here are some examples of what plant communities look like in aerial imagery vs. what they look like on the ground. I’m anticipating doing a few more posts like this, hence the “1” in the title of this post.

In the Las Cruces District, most of our vegetation is grassland or shrubland. Our two most abundant shrubs are Larrea tridentata (creosote bush) and Prosopis glandulosa (honey mesquite). Many of our grasses, especially Dasyochloa pulchella and Muhlenbergia porteri, are typically abundant hidden within either of these, or in the interspaces of shrubland rather than occurring as grassland. Our most abundant perennial “grassland” grasses include Pleuraphis mutica (tobosa), Sporobolus flexuosus (mesa dropseed), and Bouteloua eriopoda (black grama). We also have a few ubiquitous annual grasses that sometimes form annual grasslands, most notably Aristida adscensionis (sixweeks threeawn). This is what they look like:

Larrea tridentata shrubland, on the ground:

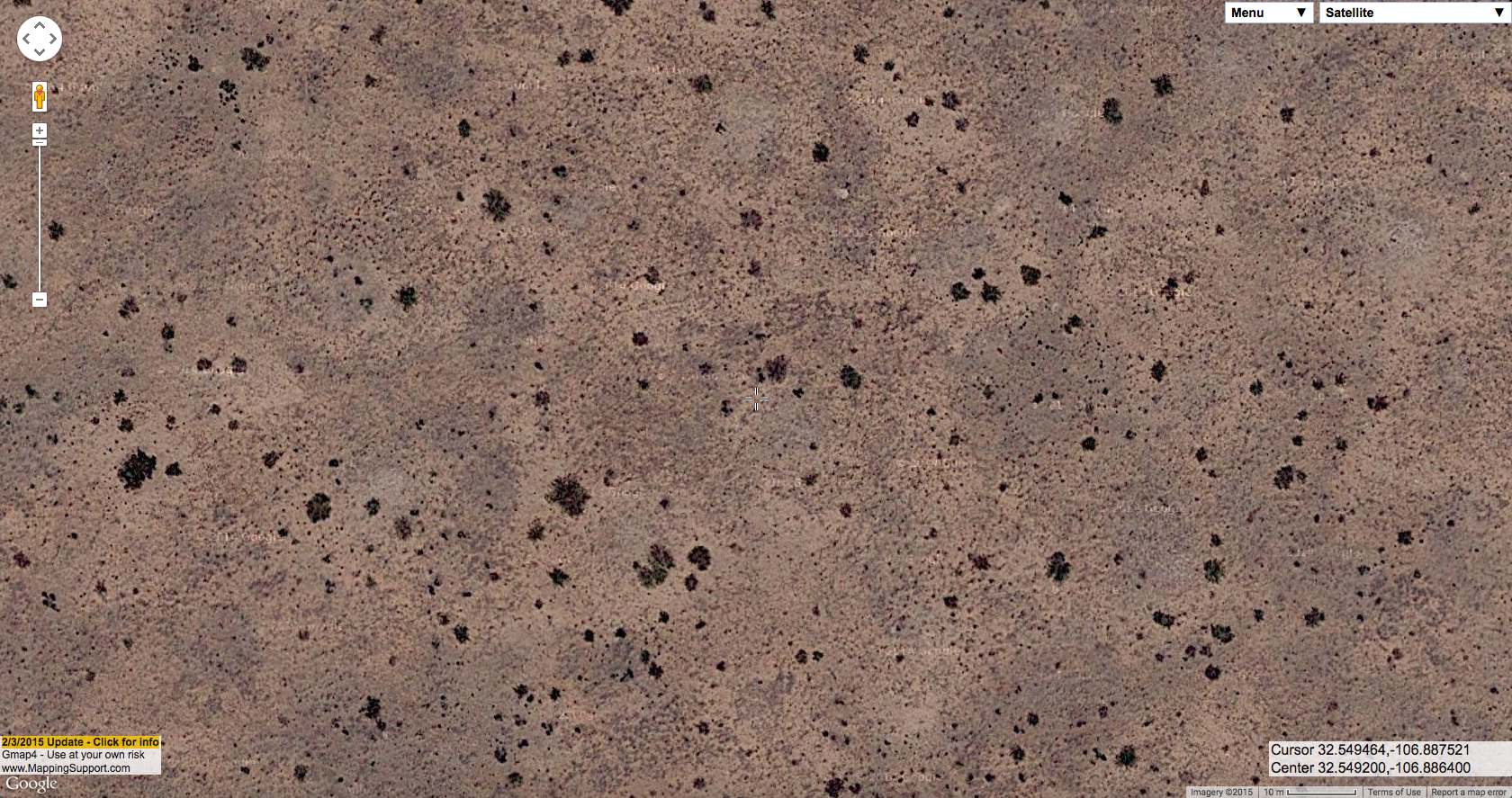

Same site from the air:

Larrea tridentata shrubland, on the ground:

Same site from the air:

Prosopis glandulosa shrubland, on the ground:

Same site from the air:

Prosopis glandulosa shrubland, on the ground:

Same site from the air:

Pleuraphis mutica grassland, on the ground:

Same site from the air:

Pleuraphis mutica grassland, on the ground:

Same site from the air:

Sporobolus flexuosus grassland, on the ground:

Same site from the air:

Sporobolus flexuosus grassland, on the ground:

Same site from the air:

Bouteloua eriopoda grassland, on the ground:

Same site from the air:

Aristida adscensionis grassland, on the ground:

Same site from the air:

In that last aerial image, you might notice that Aristida adscensionis is basically invisible in aerial imagery, but looks like a thick carpet on the ground. The aerial photograph might have been taken in a dry year, or during the middle of summer when most of the annual grasses have dried up and blown away, or Aristida adscensionis might just be too diffuse to ever be visible in aerial imagery–it tends to form fairly uniform stands that don’t offer a whole lot of contrast. Yucca elata, on the other hand, is fairly sparse but stands out prominently in the aerial imagery–that’s what most of the dark blobs are, and in a few you can tell from the shadows that you are indeed looking at relatively tall, narrow plants (at least, if you click & open the full-size image!). The smaller dark speckles in there are a mixture of sparse perennial grasses (Sporobolus airoides and Sporobolus flexuosus), perennial forbs (mostly Croton pottsii), and small shrubs (Ephedra trifurca, some small, young Prosopis glandulosa) but not very intelligible in the aerial imagery. In the next post, I think I will dive into the various flavors of Prosopis glandulosa shrubland.

All aerial imagery is via Google, using screenshots from Gmap4.