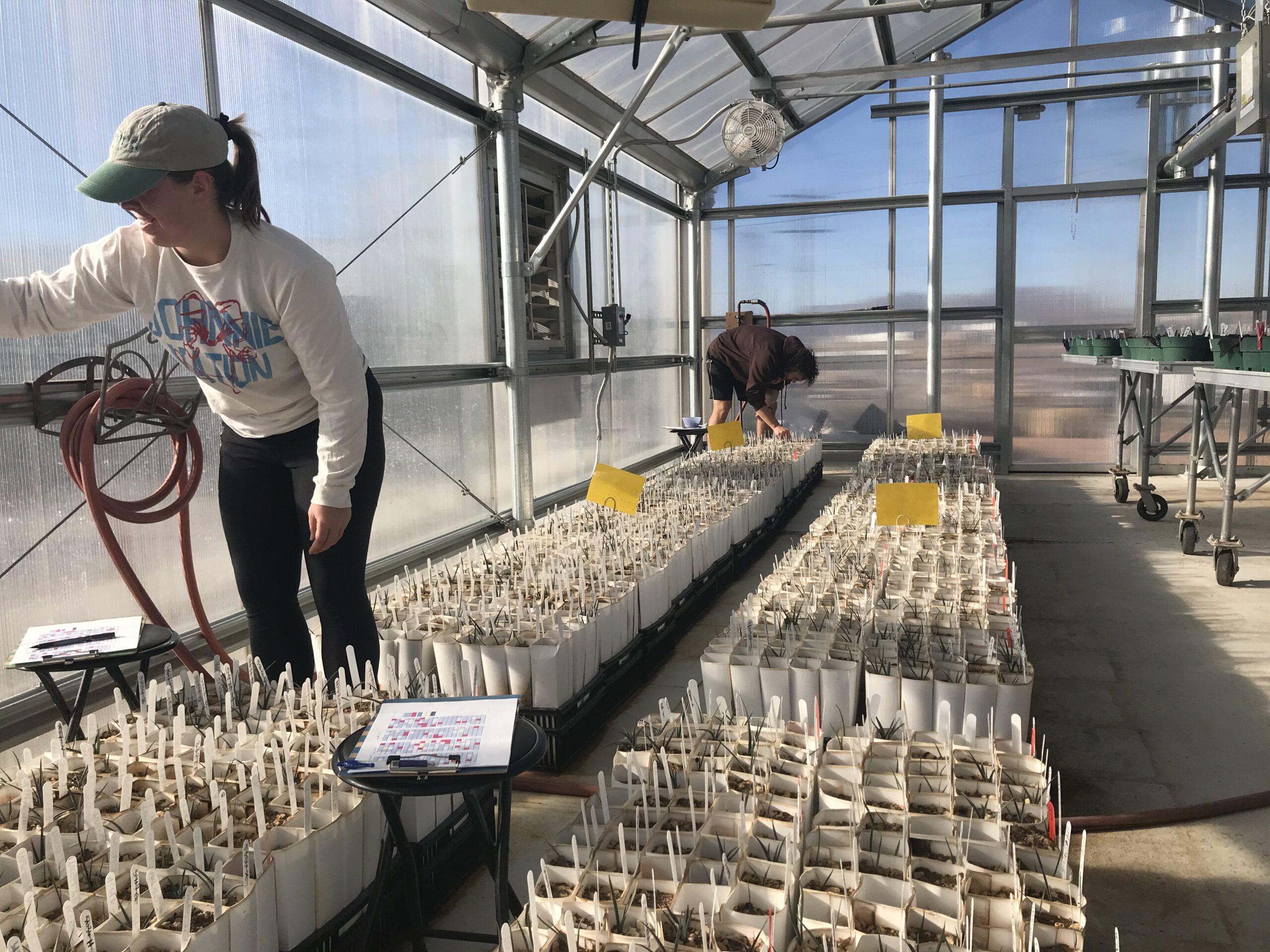

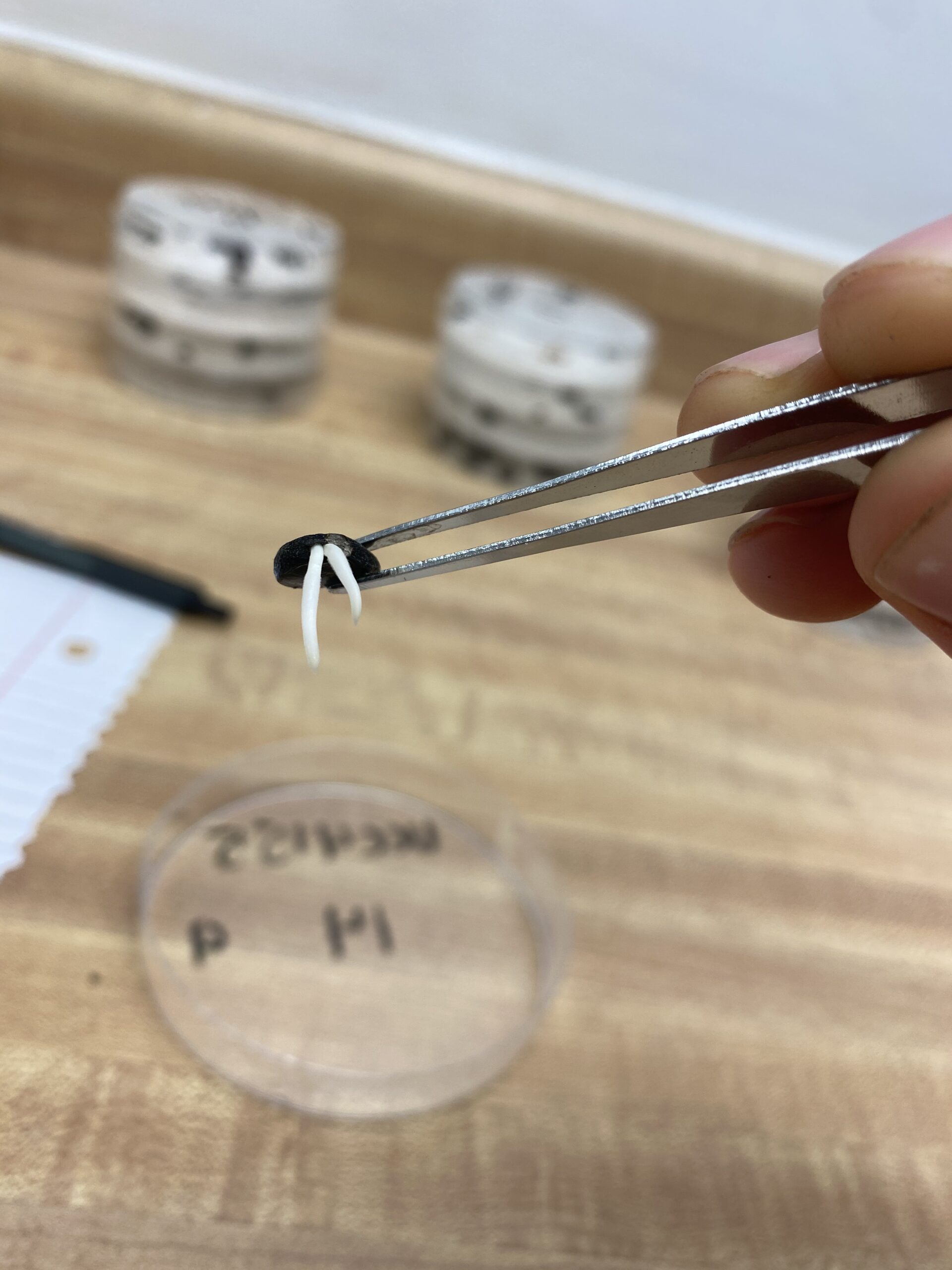

A final salute to the JTGP is in order. This New Year brings about the end of our six month stint with the USGS in Southern Nevada and the Joshua Trees. We have tracked, recorded, organized and outlined the details and info of thousands of baby JTs and are now handing that package of data over to our mentors and the future group of interns, along with a greenhouse full of growing plants with shiny metal tags, ready for out planting into the common gardens.

This internship experience with CBGs CLM program was round two for me (did an internship with the FS in Idaho in 2019) and while my first internship was a fantastic opportunity in plant conservation, management and all things botany, this JTGP internship has been a superlative introduction and lesson in botanical research. It has been an incomparable hands-on experience involving research design, time-management and troubleshooting, data collection efficiency and a dip into the statistical world.

As an individual who is intending on graduate school (and the inevitable design and execution of my own work), this internship was a much needed segue into the world of big time botanical research. I am now aware of best practices for managing study plants and just how much time and thought must go into all research. I have also experienced the struggles, set-backs and wrong turns, and have learned how to approach them with flexibility and curiosity. And most of all, I have learned the true value of working in a team. My JTGP co-interns have been with me through every one of our planning moments, hiccups, and victories. I have realized how incredibly refreshing it is to discuss courses of action with individuals who think differently and I know that we have been able to accomplish all of the work we did these past six months because of the constant support and healthy challenging that occurred as we worked together with these plants.

I also have to mention that being mentored and guided by top-tier research scientists at the USGS has been so so SO awesome. Receiving endless guidance and confirmation from Lesley and Todd has helped me to better analyze and understand the flow of this research project. I have tucked away many gold nuggets of advice and suggestions for use in my personal and professional life. They have challenged us as a group, and me as an individual, to truly dig in and open myself up to the new experiences and lessons that the JTGP had to offer.

So, it is with pride and excitement that I close this desert flavored chapter of my life. I’ll be checking in over the years to see how the JTs are doing and am so grateful to the CBG and USGS that I was able to play a roll in this amazing research 🙂