Oh, these? I brined those olives outside of Baur, take! Take more. More—

In all four years of my college experience, I had never met a man so eager to harvest the bitter little olives that grew, unnoticed, outside of the small Arts and Sciences building on west campus. Or now that I think about it, those small passion fruits too, which inhabited the butterfly garden through the late summer months, tasting like watery echoes of their relatives in the tropics. Or, even, the pea flowers that vined up the lamps besides one of our biology buildings (which ended up being toxic so we begged him to stop eating them). Or—

—uh, okay. You probably get the point.

I have a lot of memories of Stan. In the fall of my junior year, I heard Stan had tapped the maple trees on city sidewalks. Then, that he was making flour from acorns. Then, that he was going mushroom hunting in Forest Park and that all were welcome to come with. Or, most memorably in my sophomore spring, that he was making his yearly fishing trip up in Montauk State Park, and that I was invited. He was the coolest college advisor I could ask for.

Neither of us could’ve possibly known, but Stan laid the groundwork for life in Alaska.

Stan taught me how to fish. In Montauk, he showed me the way around a spinning reel on a camping lot, comparing the casting motion to throwing a frisbee. Memories of fishing puns and superstition, of the stink of bait, of camp jambalaya and marshmallows and of Stan’s fuzzy little trapper hat in the morning cold feed into my brain. His energy was contagious. When my friends and I reeled in several fish that night, he taught us how to clean them.

[Week 2, Karta Wilderness Area] After a day of filling our minds with the floral diversity of Southeast Alaska, it was time to even the playing field and fill our stomachs. Val was kind enough to lend me her fishing rod and, still not used to wearing Xtratufs, I stumbled over to the Karta river. Relying on muscle memory, I pieced the rod together and tacked on a spoon lure, taking in the rapids all around me. My friend in wildlife, Auggie, gives me a few pointers on the feeding behavior of trout and char. I listen to my line plop into the upstream, and watch it work its way down. The slack disappears, just a second, and Auggie yells at me to reel. I try to maintain my precarious balance on the rock as I do, tugging at the last second. My first Dolly Varden pops out of the water. Smaller than a rainbow trout, but tastier, I think. Stan would have loved to fish here. I wrap myself in my sleeping bag that night, feeling so lucky to have a mind swirling with Latin names and to be so utterly dwarfed by the temperate rainforest around me.

Stan taught me how to forage. I say this loosely, because the man also ate many things that he probably shouldn’t have. But what I really mean is that he imbued in me the spirit of foraging. Of being so curious and intimately aware of your surroundings that you become able to bring back some of its wonder to the dinner table. One of our mutual favorites was the Pawpaw tree. I am of the opinion that the Pawpaw is a midwestern treasure. The fruit, although short-lived, tastes as if someone had told a mango seed that it was actually a banana. C’mon now.

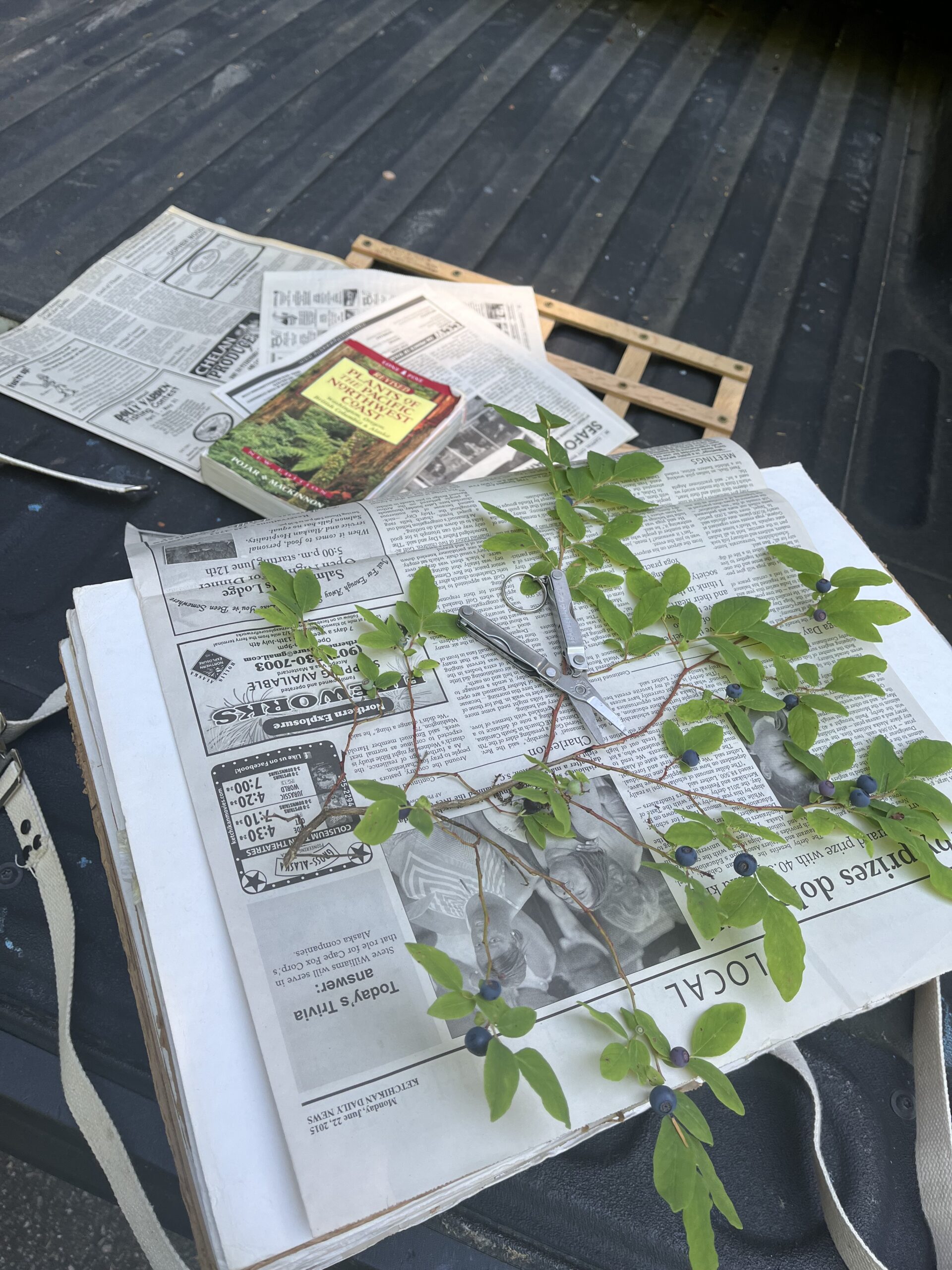

[Week 10, Gravelly Creek] We are collecting a target species today, Ribes bracteosum. The shrub is also known as stink currant. Levi and I bicker over whether the stink is the good kind or not. I contend that it is. Levi wrinkles his nose. We open up the Wildflowers of Alaska app to see if an official flora will prove one of our nasal preferences superior. As we read the annoyingly unbiased descriptions, my eye catches on a fun-fact: the frosty-blue, (pleasantly!) herbal fruits are edible (with notes describing the flavor ranging from unpleasant to mild, but I digress). I prepare everything I’ll need to start the collection, cutting a few of the berries open to get my calculations started. A vomit-green jelly, alongside some dark, angular seeds spill out. It had always made me laugh how Stan so readily popped questionable things into his mouth, giving even the least-of-choice edibles a chance. The morbid curiosity itches my brain. Anytime we’ve collected from an edible plant, I’ve had a taste. Admittedly they were mostly blueberries and salmonberries up until this point. But you learn by doing, right?

But maybe most importantly, Stan was a consistent reminder of just how fascinating the world is. I admire the way he was, always so curious about the most random of things, always encouraging his students to seek out what kept them up at night. He didn’t care about what you were already good at. What kind of work energizes you, Em? Become good at that. That was his advice. When Stan met me, I was a political science major. The very first time I went tromping in the woods was in his class, in fact. Freshman year. A city girl who needed hiking boots. I imagine that somewhere along the way, I took a turn down the right rabbit hole because here I am, still tromping around in the great outdoors—asking questions, taking notes, and eating questionable things—and I get that same childlike wonder from it each time.

[Week 12, Gravelly Creek] We map populations to gain a general sense of their density and spread. And mapping was exactly what I was doing on a warm afternoon, eyes flicking between the GPS on my iPad and the trail ahead of me. A habit ingrained into me throughout this internship has been to always be aware of your surroundings. This was usually so you could find good populations of your target species, but of course, being alert helps with spotting wildlife, weather, or dead trees, as well. So, trusting the GPS to follow my path, I let my gaze wander over the tops of the midstory, noting the abundance of Devil’s club (Oplopanax horridus) in my vicinity. O. horridus is a sprawling shrub adorned in prickles, with broad (but also prickly) leaves, and terminal clusters of red berries. It also happens to be a target species. I’ve always found it to be an interesting plant—there aren’t many others in the area that are quite as painful to touch. So I asked it a question that I ask a lot of plants these days: why are you the way that you are? Or in the case of O. horridus: who hurt you?! I didn’t expect to have an answer so soon. The sound of splintering wood had me whirling to my left. And there it was. A black bear, standing on its hind legs, pushing down on O. horridus like an uncompliant vending machine. The red berries flitted through the bear’s mouth, the animal’s thick coat fighting off thousands of years of evolution in just a couple of minutes. Were the prickles a way to ensure that only bears could propogate O. horridus’s seeds, perhaps? I pulled my jaw closed and pocketed that thought—and this potential seed collection—for later.

When you miss something or someone, you see them in everything.

In many ways, that is how I have felt about Stan throughout this internship. I’d always envisioned that I would be able to swing by campus and catch up with him. That we’d sit down, I’d pet his dog, and we’d talk about the university arboretum, weird-looking seeds, and his latest find at the thrift store. That I’d get to thank him more formally, for everything he has done to encourage my pursuance of all the wonky environmental phenomena I love.

All this to say that meandering through airport security, on the precipice of leaving home to start this internship, was the last place I expected to find out about his passing.

I think grief is an emotion that most environmentalists contend with on a regular basis. At this stage in the game of climate-change and politics, we are in a never-ending battle of loving things that we would either regret to lose, are losing, or have already lost. Here on Prince of Wales, where the vast majority of the island has already been cut down at least once, I can only look at the forest around me and wonder at what once was. At what large stands of old-growth may have looked like, at which native plants used to thrive in the places now dominated by reed-canary grass (Phalaris arundinacea), and at how differently indigenous groups may have managed the land before us. Don’t get me wrong; I deeply admire the work that the Forest Service here has done—and continues to do—to repair and prevent the errors of the past. There are so many amazing people working here, and around the world, simply because they care about that mission. But we are all working on a puzzle that was handed down to us missing a few, if not many, pieces.

There is a natural and undoubted sadness there, in that sense. We may want so badly to connect with the past, if only to appreciate and learn from it just a little longer. Loss often leaves us with an overwhelming amount of love and this bitter desire to please just put it somewhere, even if that somewhere seemingly no longer exists. But what we do have is right now.

This internship has taught me many practical things about the kind of conservation work I want to embody moving forward, but on a more personal level, I’ve learned to see the work I’ve done here as a way to honor Stan’s legacy. I hope that through all my rambling, it’s become clear that Stan is a crucial part of why I am here, now.

So, to my college advisor, my professor, and always my friend: Stan, you’re the man. I see you in the trees (and wow are there a lot of them in the forest, who knew) and in every funky-flavored fruit I put in my mouth. I see your influence in every person who was lucky enough to witness your love for nature in action. I find your spirit in all the people who share echoes of your gentle wit and wonder. And, when I’m outside, I try to experience all these beautiful places through your eyes, even if it’s for just a moment. Let me share something with you, this time.

I miss you, Stan. Thank you for everything.

And thank you, Alaska. You have been brilliant.

I’m gonna let you go, now.

-Emma