As I drove through the forest on my last field day, I looked out the window, staring at those big ol’ Fir trees I now know and love. I began to process that this would be the last time, for a long time, that I would see this forest. When I first arrived in the Willamette National Forest, I was starstruck. Everything looked like a dream. I wondered if people out here ever got used to the beauty. Now, as I come to the end of my season, I ask myself the same question.

To answer it simply, no.

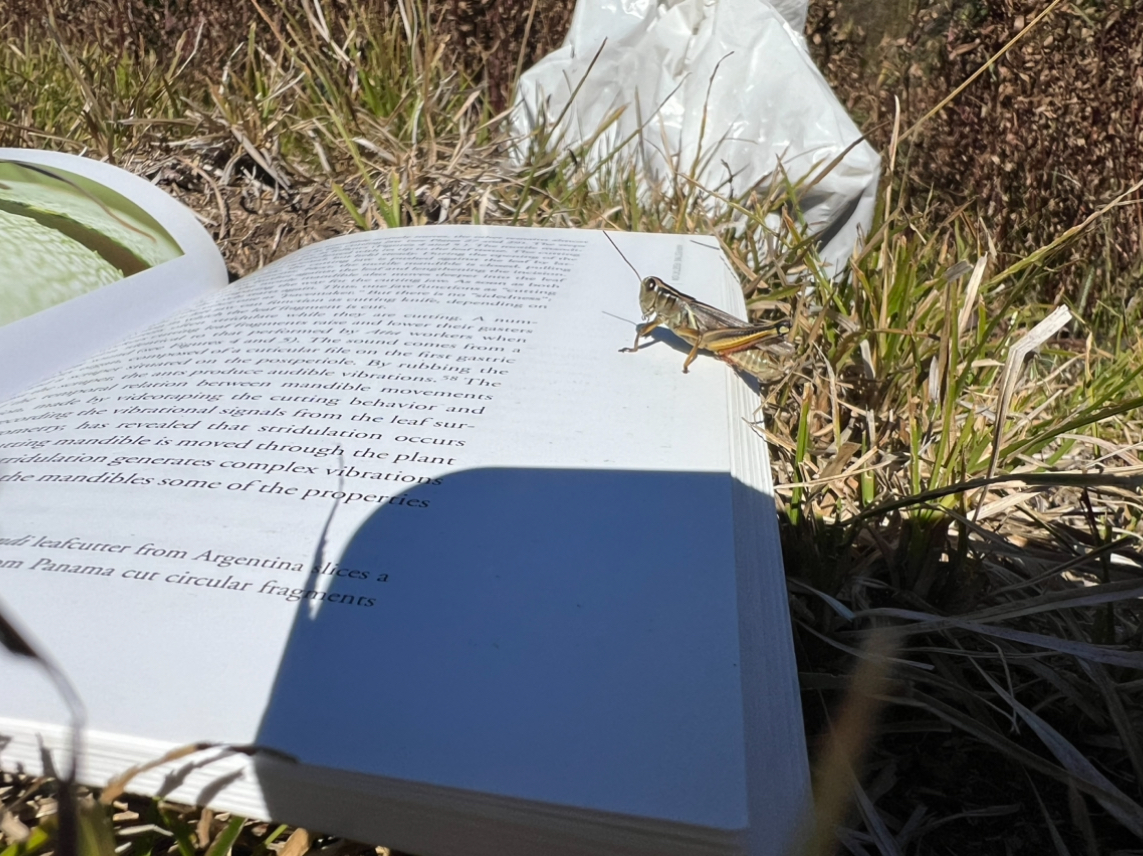

To explain further, I don’t think it’s possible to get used to it. I’m never looking at the same exact thing. The more I look at the forest, the more I find another hidden detail – a tiny cove in a riverbed, a little beetle crawling on leaves, or even just a beautiful overlook. During my time out here, I’ve been fortunate enough to witness the seasons change from early Summer to late Autumn. When I first arrived, Mt. Jefferson was coated in snow, then I watched the glaciers melt to reveal bare rock, and now, in my final week, the snow has returned. I’ve loved being up close and personal with the passage of time.

The forest changes constantly. We watched the flowers bloom into mature seeds, and the fruiting of huckleberry bushes are now replaced with fruiting fungi on the forest floor. Our sunny days are instead replaced with cloudy rain, and the forest looks completely different after rainfall – the moss is brighter, the river runs faster, and the newly fallen trees block our path. The animals go in and out of hibernation and mating – the birds I heard in early June are now replaced with October crow squawks. The roads that made me feel like I was going to summer camp in a blockbuster film now fill my mind with the tune of “Winter Wonderland”. The lighting, the colors, the noises, the weather, and even the feel of the forest are changing constantly.

So, maybe I can’t say if I’ve gotten used to it because this forest isn’t the same as when I began. There are constantly new things to learn and new ways to understand what’s going on. As soon as we scientists think we understand the way of the land, some new research comes out revealing another one of nature’s secrets, changing how we see everything. With each piece of information I learn, I look at the forest differently.

Despite all of the changes, this forest does feel like home. All the plants that used to blur together, now feel comforting to me, like seeing an old friend. I look at the forest differently, but in a way that you look at a friend differently when you begin to understand them deeper. Even if everything wasn’t changing, I don’t think I would get used to it. Beauty isn’t something you get used to or bored by. I feel like true beauty is something you appreciate every time you see it because no matter how long you stare, your brain will never be able to comprehend how something so divine was created. So, goodbye Willamette – I hope you know how beautiful you are.