Spring has come to the Mojave Desert! Annual plants are opening their flowers, birds are active and singing, and we’re leaving behind the cooler days of winter (well, relatively cooler, sorry Chicago). Expect pictures and stories about flowers to come soon, but I’m still trying to figure out what all of these new species are. So with this blog I’m going to talk about critters. Scaly ones.

Lizards are some of the most noticeable and most charismatic Mojave Desert fauna. During the warmer months, I could hardly walk 10 meters through the desert without coming across one of these little reptiles. I seldom picked them out as I approached their hiding spots, but when I got too close they would dart away, scampering wildly across the sand looking for refuge. The fleeing lizards were a welcome source of entertainment and movement on the otherwise oppressively still and hot summer days. Most of the lizards here remained active into October and November last fall, spent the cooler winter underground, and have started to reappear in the last few weeks. Allow me to introduce you to some of them.

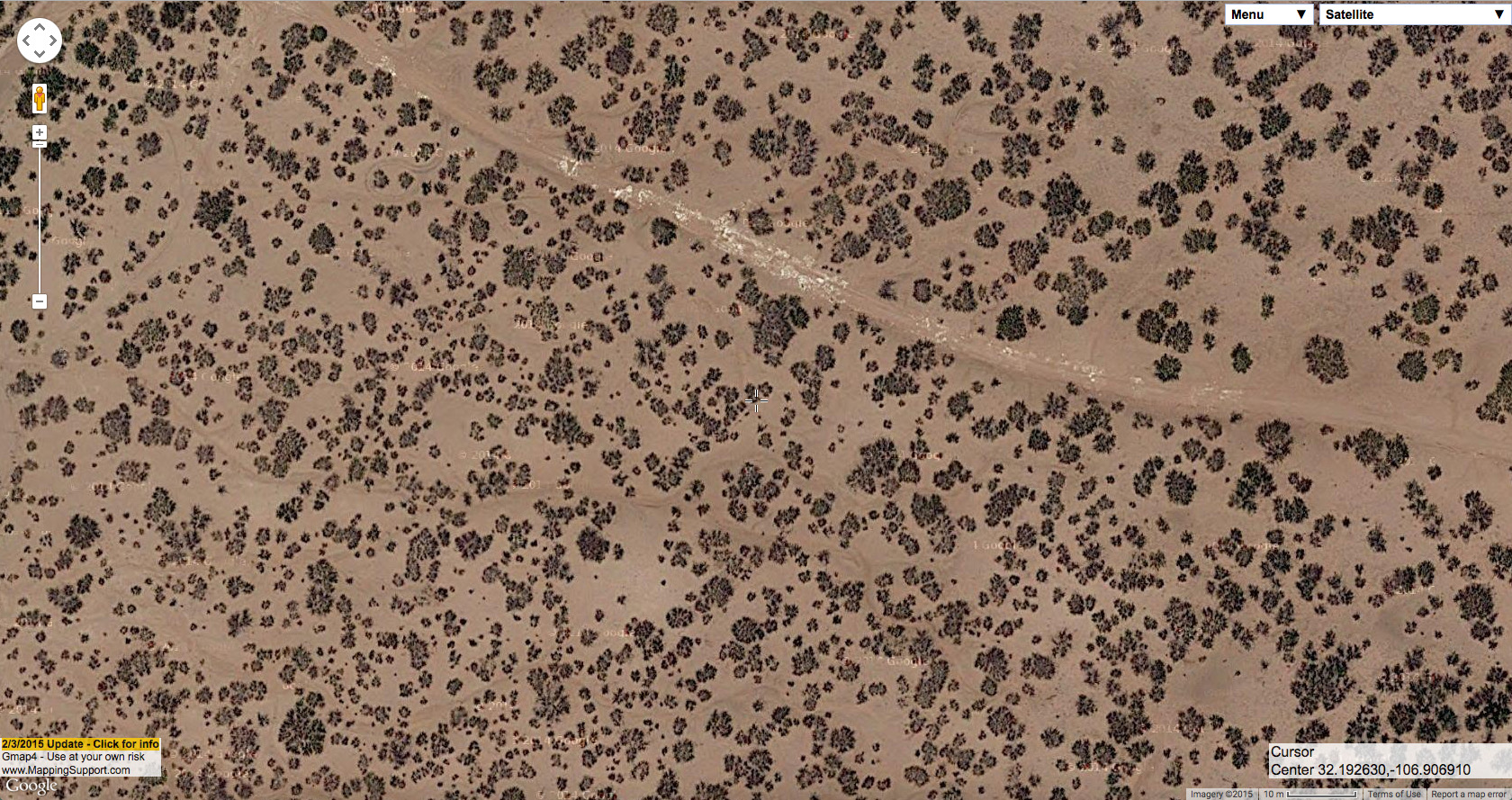

A western side-blotched lizard. This guy either thinks that I can’t see him, or he’s trying to decide if he can take me on.

The most common lizard in my part of the Mojave is the western side-blotched lizard (Uta stansburiana elegans). This extremely abundant species is typically the one that I send scattering as I walk through the desert. These lizards are small, only growing up to 4-5 inches long. They can move with great agility and quickness as they run or hop through boulders and shrubs, which helps them to catch their preferred meals of small insects and spiders. One reason I find lizards entertaining is that they seem to have quite a bit of attitude. The males of several species, including side-blotched, can be territorial, and one of the ways they show-off their dominance is by climbing to the top of a boulder, standing up tall on their four legs, and rapidly doing push-ups. Even as I approach, these guys will sometimes stare me down and continue their push-up routine, showing off how tough they are, until finally I get too close for comfort and they run off. That’s pretty bold for a small animal. I think it’s great.

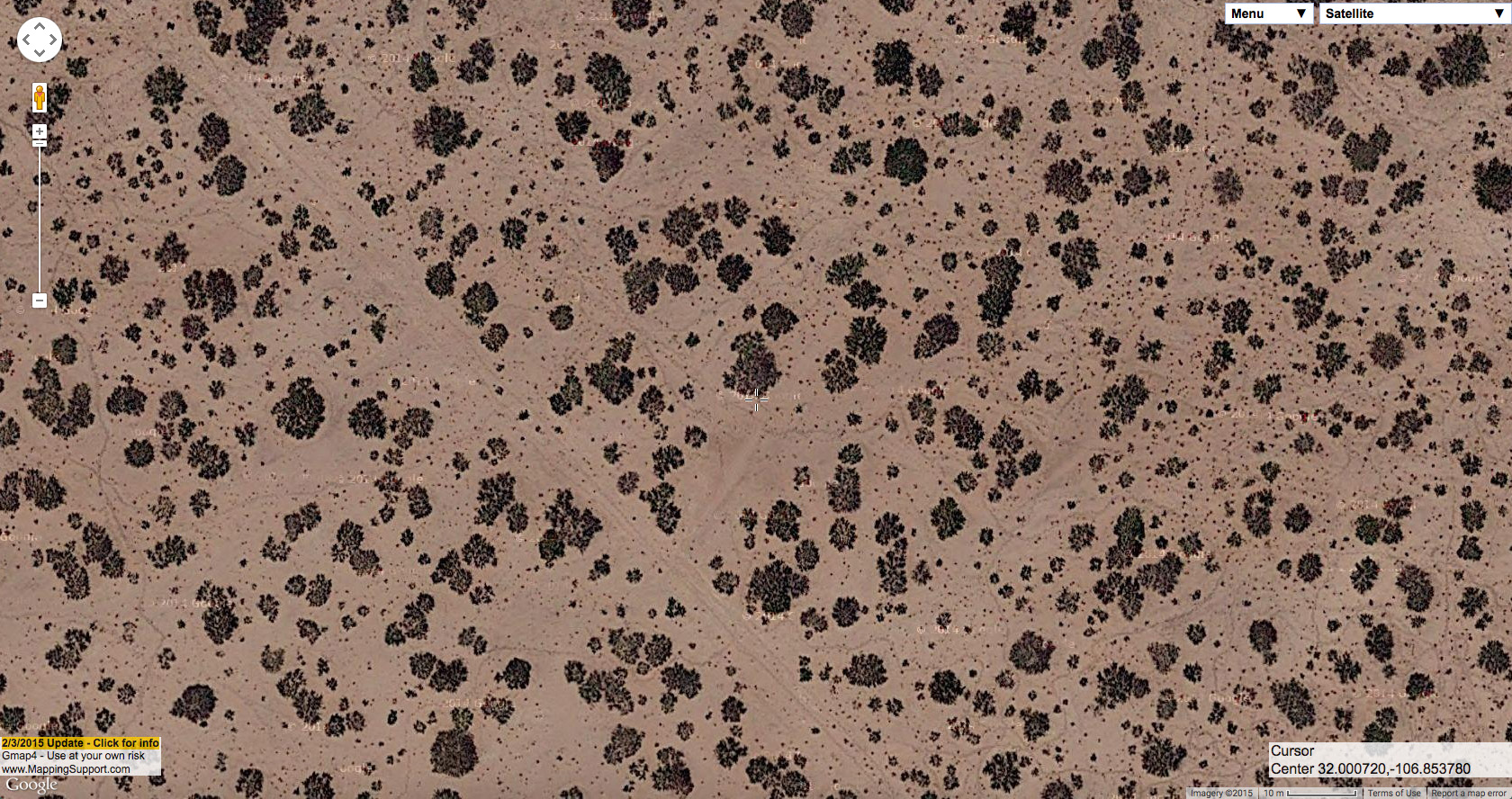

The western zebra-tailed lizard. Take a look at those great big hind feet with the long toes. Those things make this lizard very fast. A whole lot faster than me.

Western zebra-tailed lizards (Callisaurus draconoides rhodostictus) are another common desert species. Like side-blotched lizards, they are fairly small in size, but show a surprising amount of spunk and affinity for showing off their pectoral fitness. In the picture I’ve shared you can see the dark and light striping on the tail that gives this species its name. You may also be able to see just a little bit of bright color on the belly of this lizard. During the breeding season, their undersides are brilliantly blue, yellow, and orange. Zebra-tailed lizards are one of a couple species that could claim to be the fastest in the desert, and they have a habit of running with their striped tails curled up, adding to the list of behaviors that make lizards charming and comical.

Western zebra-tailed lizard. If you look at the edge of its belly, you can see just a little bit of the brilliant colors that this lizard has underneath.

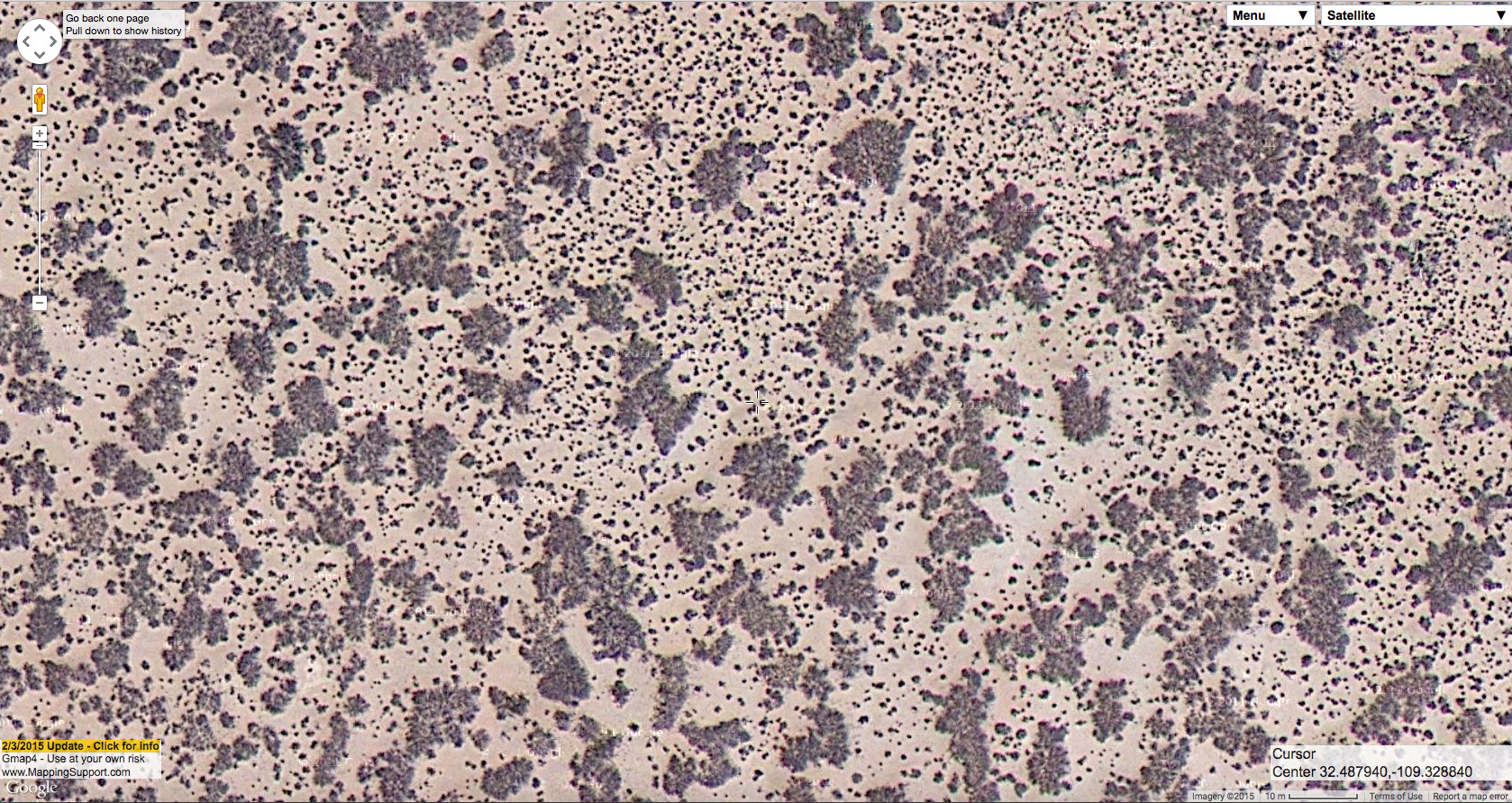

Horned lizards are distinctive and widely recognizable, and the species I’ve come across here is the southern desert horned lizard (Phrynosoma platyrhinos calidiarum). Though not as fast or nimble as some other species, their wider bodies and spiny armor give them protection from many predators. And yes, they can squirt blood from the corners of their eyes as a defense mechanism. They don’t do it very often, but all the same, that is one wild behavior. However, their best defense against predators is their camouflage. The coloration of horned lizards will typically match that of their local habitat, mirroring the soil color in which they live. I have only seen three horned lizards during my time here, but I have surely walked past many more without knowing it. Ants are the preferred food for this species, and they have a sticky tongue that helps them to capture their prey.

This is a southern desert horned lizard. You’re going to get several photos of this species, because I think they are really beautiful.

When I try to take pictures of lizards, they usually make me look very slow and very foolish. But sometimes, if they think they’re hidden, they’ll sit nice and still for me. Like this one.

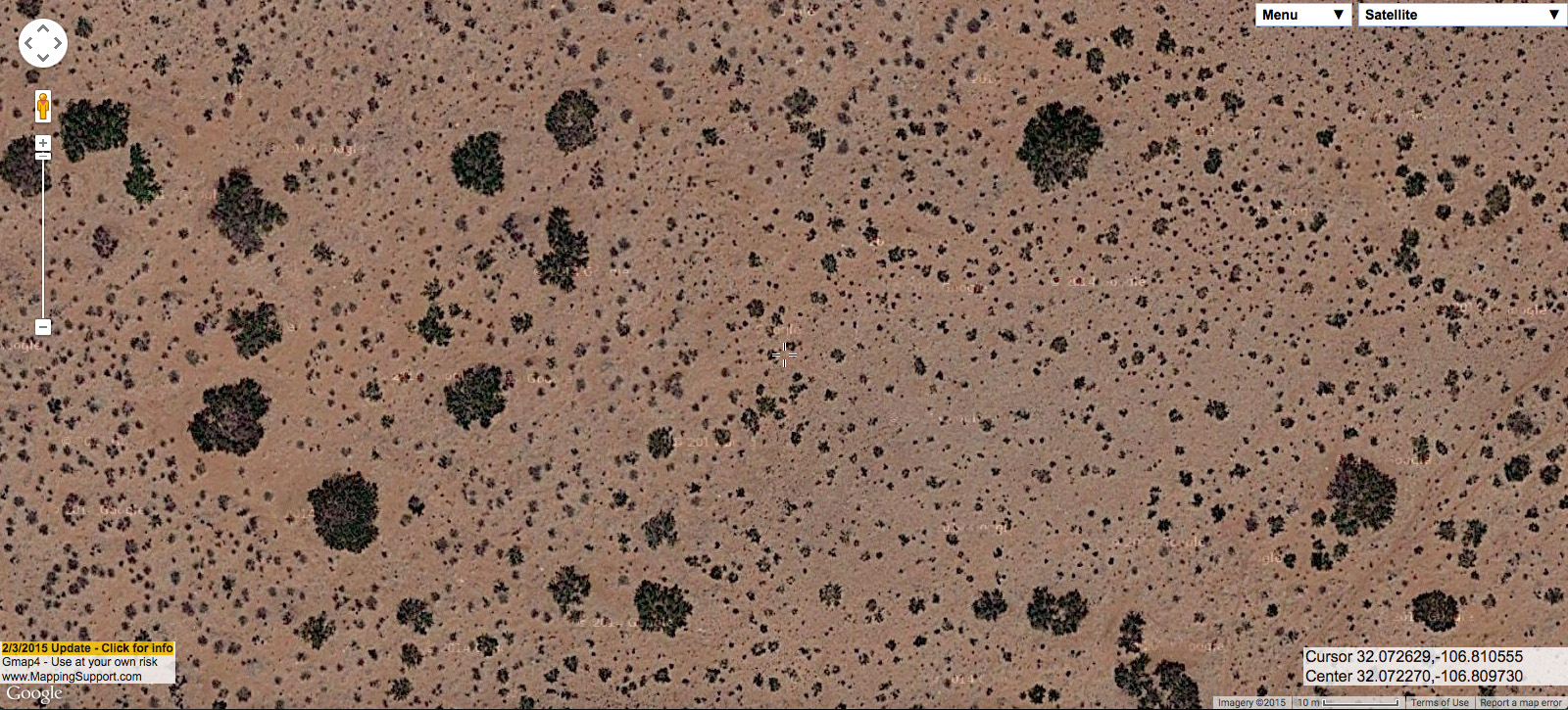

Northern desert iguanas (Dipsosaurus dorsalis dorsalis) are a larger lizard, growing to 16 inches including the tail. This species is also in the running for the title of “Fastest Lizard in the Desert.” Even more impressively, desert iguanas may be able to tolerate higher temperatures than any other North American reptile. They can remain active even during the middle of 120° F summer days. Unlike the other lizards I’ve shown you so far, this species is primarily herbivorous. They eat a particularly large amount of flowers and leaves from creosote bush (Larrea tridentata), the super-abundant shrub that dominates the Mojave Desert.

Northern desert iguana. You know what it’s thinking? “Hey you, with the two legs. Why don’t you come down here and try to catch me? I dare you.”

The long-nosed leopard lizard (Gambelia wislizenii) is another medium-sized species. They sometimes eat plant materials, but leopard lizards also live up to their name as a predator. They lie camouflaged and hidden in the shade of a shrub, and then pounce on their prey with a burst of speed. They eat insects and arachnids, but larger animals like rodents, snakes, and other lizards are also on the menu. Leopard lizards will cannibalize their own species, and will sometimes go after prey nearly as big as they are.

A long-nosed leopard lizard. The spots and its appetite for large prey make this lizard’s name an appropriate one.

I’ve come across a few more lizards, such as big-eyed, nocturnal geckos and the very large, leathery chuckwalla, but I’m afraid that’s all the photos I have to show you. Lizards aren’t always so good about sitting still to have their pictures taken. And there are two species in particular that I haven’t come across yet, but would love to. One is the Mojave fringe-toed lizard (Uma scoparia), a dune-dwelling species of special concern here in California. Hopefully I’ll get to see them as I visit sand dune habitats this spring. The other is the more well-known banded Gila monster (Heloderma suspectum cinctum). With a beautiful, bold, orange and black body, Gila monsters are the largest lizard in the United States, and are one of only a few venomous lizards in the world. They are seen in our field office from time to time, but are not common at all. Of course, I would LOVE to see one, but it’s a long shot. If I do, there will definitely be pictures posted to my blog.

Thanks for reading! Until next time!

-Steve

Needles Field Office, BLM