‘Twas noon before my last day, when all through the office,

Not an employee was stirring, not even the botanist.

The plants were stored in the cabinet with care,

in hopes that new interns soon would be there.’

Such is the atmosphere at the Carson City BLM Office while I wrap up my botany internship; most employees have already left for their vacations and those who are still here quietly work while waiting for the holidays to arrive. The past several weeks have been spent catching up from the busy field season, processing plant vouchers, and preparing helpful training materials for the next group of interns. So much time in the office has given me time to reflect on the internship and what I have learned while living and working in the Great Basin and Sierra Nevada mountains. I have broken into sections the various musings and reflections I have had over the past days.

Botany

Castilleja chromosa in full bloom in Lassen County, California.

Identifying plants is at once relaxing, fun, and painful. Often, you think you have the correct identification only to read through the description and illustrations to find you are way off the mark. As frustrating as this process is (which usually depends on the quality of your specimen), most times you find yourself delighted with the ease of identification (especially if you have a spectacular specimen)! Many hours have been spent at the microscope, blissfully and fretfully keying out plants from the 2015 season as well as from years past. Here is a link to a poem I wrote in the midst of working through the piles of plants to identify.

How to Use a Dichotomous Key: A Poem

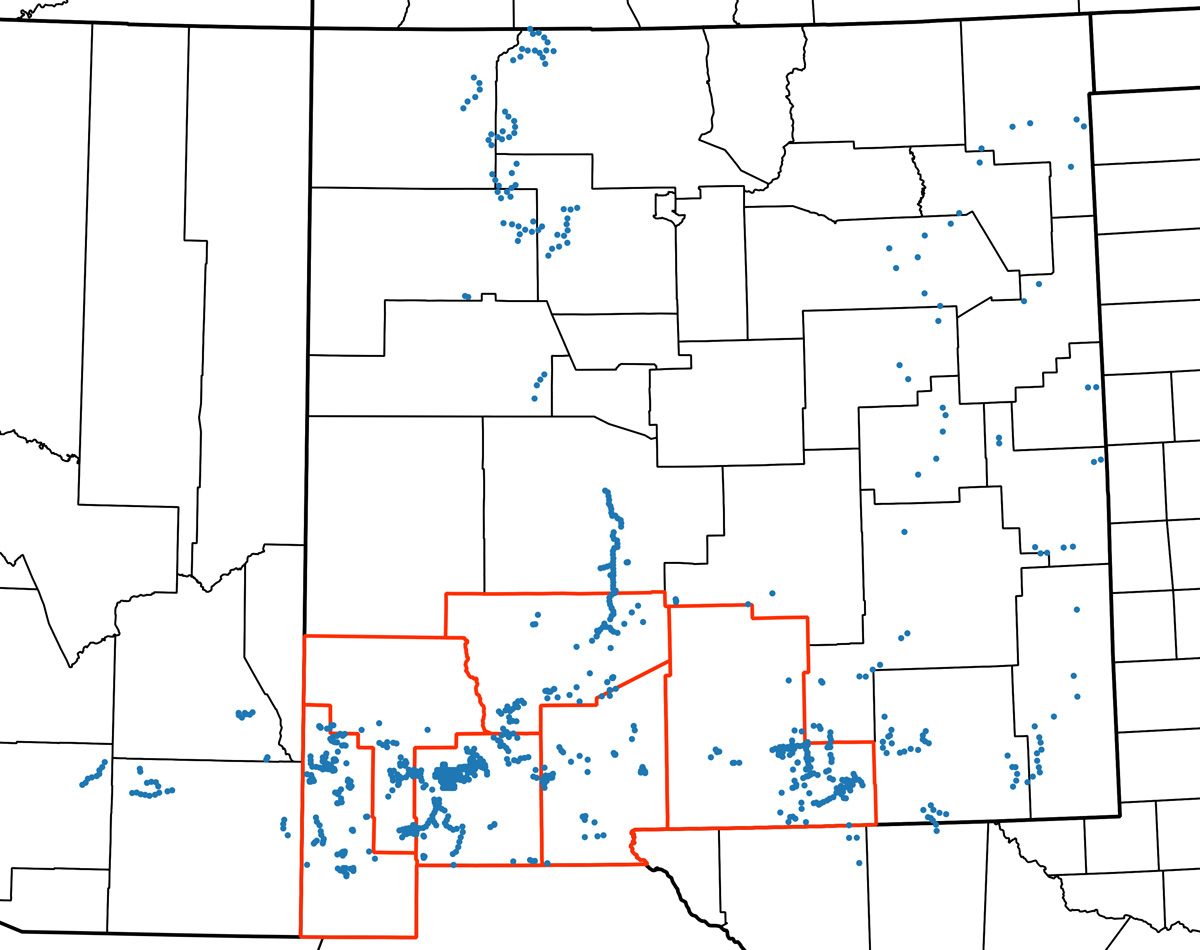

After I had processed most of the plant vouchers, I then set into updating the herbarium database for the Carson City office. The herbarium has vouchers dating back to the 1960s, providing valuable information about the plants of the area. My goal for organizing the data was to make a GIS shapefile available to the BLM Botanist and future interns so they could manipulate the data for their own conservation and land management purposes. I also used this data to build a list of ‘collection hot spots’ for future intern teams. I looked at vouchers collected over the years for Seeds of Success collections and found several heavily-scouted areas where seed collections were still waiting to be made. Being able to see where future intern teams could go for some quality seed collecting helped me connect the dots between the variety of work assignments I had completed this summer. At the beginning of my internship, I was so overwhelmed with the new area and the new plants to be able to settle down long enough to come up with a game plan for the season. Our team was still super productive under our supervisor’s guidance, cranking out 133 seed collections, but I hope my efforts at the end of this season will help next year’s group be even more efficient.

One final thought on botany: I hope I am able to see another desert spring in my lifetime. Again, I was so busy and overwhelmed in the spring and early summer to appreciate the beauty of the short-lived season of color here in the Great Basin. I would love to see the spring colors again so I can really take time to appreciate them.

Purshia tridentata flowers paint the landscape a soft yellow in the spring.

Adjusting to the West

Learning my way around the western side of Nevada and the mid-eastern portion of California has taken the majority of the internship, but has been quite rewarding. Navigating to rural areas of Nevada for seed collecting and fire monitoring took a lot of spatial awareness as well as the ability to use common sense while following a not-always-so-accurate GPS. Just driving on some of the back roads of Nevada requires patience, stamina, and flexibility. Most roads are super bumpy and sometimes roads will be washed out too. Impassable roads (or getting stuck halfway down an unknowingly impassable road) delays the work day and the only thing you can do is pull yourself out of the predicament and find another route. Having flexibility in these situations is so helpful when everyone is stressed and worried.

The 2015 team digs out the truck from a very wet drainage area in the Pine Nut Mountains.

Another adjustment to the west is the sheer size of the states. Being from the Midwest, I could travel between states within a few hours. Out here, it could take you a few hours just to travel from one county to another! Learning to allot several hours to travel anywhere definitely takes some of the spontaneity out of weekend trips, but the sites to see are so worth the time to get there!

One project I completed near the end of the internship was an ESRI Story Map journal that highlights the Carson City internship experience and leads viewers on a tour of some of the areas of interest throughout the range of the Carson City intern team. The Story Map web application is a powerful tool for telling your story or making information accessible and visually stimulating. It was exciting to be able to pull together the past twelve years of intern experiences into one place so future interns can acquaint themselves with the area before heading out into the field. While there is always value in self-exploration of a new area, having access to the Story Map resource will make it easier for future interns to plan field work and understand the large-scale scope of the Carson City internship. Check out the map at the link below!

ESRI Story Map Journal: Life of a CLM Intern in Carson City

Wildlife and Weather

While most days in the desert consist of cloudless, bright, sunny skies and breezy-to-gusty winds, sometimes the weather is unpredictable. One evening in May, our team was out doing rare plant monitoring and a snowstorm blew in as we were setting up camp for the night. I didn’t realize it was supposed to snow, so I didn’t have all of the layers with me I normally bring for cold nights. It was so cold that night, I ended up sleeping in one of the trucks so I could stay warm! I never forgot my layers after that experience! Always having enough layers for the surprise storm or just for the cold desert nights is a crucial part of being prepared in the desert. Surviving in this ecosystem requires more than just bringing enough water!

Most of the 2015 team huddles around a campfire in May after a snowstorm blew in overnight. Photo credit Olivia Schilling

As for wildlife, nothing compares to waking up in the middle of the night to the stars shining above you and the sound of a coyote pack crying to the moon. I still get excited chills thinking about the countless nights this summer when I found myself in this situation. On the nights when I opted to sleep completely under the stars instead of in my tent (which never made it out of its bag as summer progressed), I was reminded of just how close the coyotes were and how exposed I was at that moment. As amazing as it is to hear coyotes howl, it is slightly unnerving to know they could run past you at any moment.

Another animal that is always neat to see is the wild horse. Running into a pack of horses grazing in the sage brush is quite an experience even when you realize the havoc they wreak on the environment. Our group was lucky to see a handful of different horse groups throughout the summer, but the most involved encounter was at the Palomino Horse and Burro Ranch north of Reno. While doing weed surveys here, we were able to interact with some of the horses who were begging for some pets. 🙂

Wild horses at the Palomino Horse and Burro Ranch lean through the fence to beg for some pets from interns.

Final Thoughts

As I wrap up my time in Carson City, taking time to reflect on all of the adventures I have had while here has been helpful as I transition into the next stage of my career. I do not know yet where I will be going after this, but I am excited about the possibilities that have opened up because of the skills I have learned through this internship. I am incredibly grateful to have been an intern with the BLM as well as the CLM and Seeds of Success program.