Let’s set the scene.

The date is July 27th, 2020 in Boulder City, Nevada. The air, well over 100 degrees, feels like you’re standing in an oven on full blast. The roads are littered with tumbleweeds, like actual tumbleweeds straight out of a cartoon. Surrounded by a desert filled with coyotes, rattlesnakes, and tarantulas. This is what I walked into as a newly recruited intern for the Joshua Tree Genome Project at the USGS.

After losing an internship due to COVID-19, I was desperate, scratch that, very desperate, to find work anywhere I could. Call it fate, divine intervention, or just dumb luck, I received an email late May informing me of a position open in a little town just minutes away from Las Vegas. So, I packed up my Jeep and made the 26-hour drive from Northwest Arkansas to the Mojave Desert, having no idea what I was in for. Little did I know that it would be one of the most rewarding and enriching times of my life.

Over the past 6 months, me and my fellow interns have put blood, sweat, and tears into the Joshua Tree Genome Project. From breaking open pods and counting thousands of seeds in a basement, to working in a greenhouse until 2 am planting those same seeds, our time on this project has been nothing short of an epic adventure. We have spent countless hours mauling over massive excel datasheets, so much so that we began to dream about data, pivot tables, formulas, and Rstudio scripts. We spent days upon days camping in the desert where, much to my extreme delight, I was able to encounter the Mojave Green Rattlesnake (Crotalus scutulatus) for the first time. We camped under the stars and worked in the blazing heat, assessing the growth of plants that interns in previous years had planted. We met incredible people along the way, but none more so than Dr. Lesley DeFalco and Dr. Todd Esque.

Dr. DeFalco and Dr. Esque, or as we now call them, Lesley and Todd, have been the most amazing mentors I could have ever asked for. Through their guidance and leadership, we have been able to achieve things I would never have imagined 6 months ago, and their attention to detail and effective communication skills have left a lasting impression on all the interns. They have been patient, understanding, unfathomably useful, and a joy to work with.

I have nothing but praise for my fellow interns as well. Moving across the country can be a culture shock in and of itself, but add on three strangers from very different locations, the move can seem much more daunting. However, I wasn’t prepared for some of the nicest, smartest, and most hardworking group of people I would have the privilege to call my fellow interns. They have taught me so much and have been a great “quarantine” squad over the past 6 months. My roommate, Nick, has been a constant source of laughter, inspiration, and random nonsense, I a will look back at my time at 629 Avenue L fondly because of him.

My time in the desert has been the time of my life. I have learned from experts, gained some valuable contacts, and made lifelong friends. I look forward to reading the papers that our work will produce, and I can’t wait to see how our findings are used in the future.

Well, that’s all for me, I have lots of work to do, and my time in Boulder City is limited.

Thank you CBG and the USGS for a wonderful experience

Josh

Signing off on the JTGP

A final salute to the JTGP is in order. This New Year brings about the end of our six month stint with the USGS in Southern Nevada and the Joshua Trees. We have tracked, recorded, organized and outlined the details and info of thousands of baby JTs and are now handing that package of data over to our mentors and the future group of interns, along with a greenhouse full of growing plants with shiny metal tags, ready for out planting into the common gardens.

This internship experience with CBGs CLM program was round two for me (did an internship with the FS in Idaho in 2019) and while my first internship was a fantastic opportunity in plant conservation, management and all things botany, this JTGP internship has been a superlative introduction and lesson in botanical research. It has been an incomparable hands-on experience involving research design, time-management and troubleshooting, data collection efficiency and a dip into the statistical world.

As an individual who is intending on graduate school (and the inevitable design and execution of my own work), this internship was a much needed segue into the world of big time botanical research. I am now aware of best practices for managing study plants and just how much time and thought must go into all research. I have also experienced the struggles, set-backs and wrong turns, and have learned how to approach them with flexibility and curiosity. And most of all, I have learned the true value of working in a team. My JTGP co-interns have been with me through every one of our planning moments, hiccups, and victories. I have realized how incredibly refreshing it is to discuss courses of action with individuals who think differently and I know that we have been able to accomplish all of the work we did these past six months because of the constant support and healthy challenging that occurred as we worked together with these plants.

I also have to mention that being mentored and guided by top-tier research scientists at the USGS has been so so SO awesome. Receiving endless guidance and confirmation from Lesley and Todd has helped me to better analyze and understand the flow of this research project. I have tucked away many gold nuggets of advice and suggestions for use in my personal and professional life. They have challenged us as a group, and me as an individual, to truly dig in and open myself up to the new experiences and lessons that the JTGP had to offer.

So, it is with pride and excitement that I close this desert flavored chapter of my life. I’ll be checking in over the years to see how the JTs are doing and am so grateful to the CBG and USGS that I was able to play a roll in this amazing research 🙂

Unlocking My True Self

A MOMENT IN TIME

In the time that I’ve been in Marlinton, West Virginia, I have learned so much about myself. And I’ve been able to challenge many of the thoughts and ideas that I had when I first came into this experience. Every single day, I grow more and more in love with the person that I am becoming, my true self. About two and half years ago (my last semester as a junior in college), I thought I’d take a gardening course because it sounded like fun and I wanted a break from the animal science course load. I had convinced myself for so long that I wanted to be a veterinarian. So, when that dream started showing cracks and I didn’t know how to fix it, I felt utterly lost and hopeless. Little did I know, when I took that gardening class, that the trajectory of my entire life would shift so abruptly and yet so perfectly. As serendipitous and exciting as it felt to realize my passion and to change my major, it was nerve-wracking to tell my family. A part of me wishes that my past self had a glimpse into my life now as it would’ve calmed the uneasiness of telling them. As stressful and disheartening as it was, I’d go through it all over again just to be where I am today.

Caroline and I on our first outing to Lewisburg, a town an hour away.

Gleefully picking elderberry

First trip out to Dolly Sods with Todd Kuntz

A backseat full of seeds. This was right before handing over our last bit of seeds to Morgan at Appalachian Headwaters.

MY CHOSEN FAMILY

Through my time here, I had been able to establish and nurture unique relationships with the people around me. From those that I worked with in the forest service to my co-intern, Caroline, and my numerous roommates.

However, the greatest connection that I made was with my roommate, Michael. Being the incredibly funny and cool guy he is, it was inevitable that we would be good friends. Our personalities clicked so well and felt complementary to each other that he quickly became one of my best friends and also like the big brother I’ve always wanted.

I find it necessary to highlight and emphasize the relationships that I developed during my program because they played a key role in how positive my experience was.

While I wasn’t subjected to overt racism, I did encounter microaggressions that left me feeling upset, singled out and alone at times. I would be lying if I said that I was surprised by it. It was rural West Virginia after all. Without their love and support, my time in Marlinton might have been sullied by those few awful moments. I feel incredibly lucky to have been surrounded by such kind and compassionate individuals who were always there to listen and be allies.

FINDING MY SPARK

While my many friendships were indeed bright spots in my internship, the work that Caroline and I were able to do brought me excitement and so much pride. After having done one odd job after the other during and in between semesters, I had never known what it was like to do something that gave me purpose. Never had anything afforded me the feeling of being a part something bigger than myself. This program allowed me to grow and discover my spark. A spark that has expanded into a wildfire that fills me and pushes me to do more.

My future feels so much brighter now than when I first got to West Virginia, which feels like a century ago. While I’ve since left the state to spend the holidays with family and to head back to Florida, I’ll actually be returning a lot sooner than anticipated. Just two days before we rang in the new year, I was offered a position with Appalachian Headwaters, a non-profit organization that we worked closely with during our program to process and store our seeds for the forest service! I’ve been buzzing with excitement since and I cannot wait to see what is in store for me.

Signing off

-Ivy

Driving out of the Alleghenies

One week ago, I drove the rickety bridge over Brown’s Run for the last time. I turned right, past the field of ironweed and wingstem aster, past the horse pasture and the barn, then turned left toward Huntersville, heading east on Route 39. My 4Runner was packed to the gills, weighted down with several new additions since I arrived in Marlinton in July. Atop the center console was my newest friend, Moona, a young stray cat who adopted me on a camping trip at Tea Creek in late November. In my cooler was a bag of frozen foraged chantarelles, remnants of the final mushroom haul in October. Stuck between the pages of field guides and biology textbooks were pressed herbarium specimens of Dryopteris intermedia and Athrium angustum, which I picked up on a botany survey in September. Packed away in a small box at the bottom of the heap were botanical drawings of some woodland flora, which I made while memorizing species in August. I was driving away from Marlinton, loaded down with five months’ worth of gifts from my experience there.

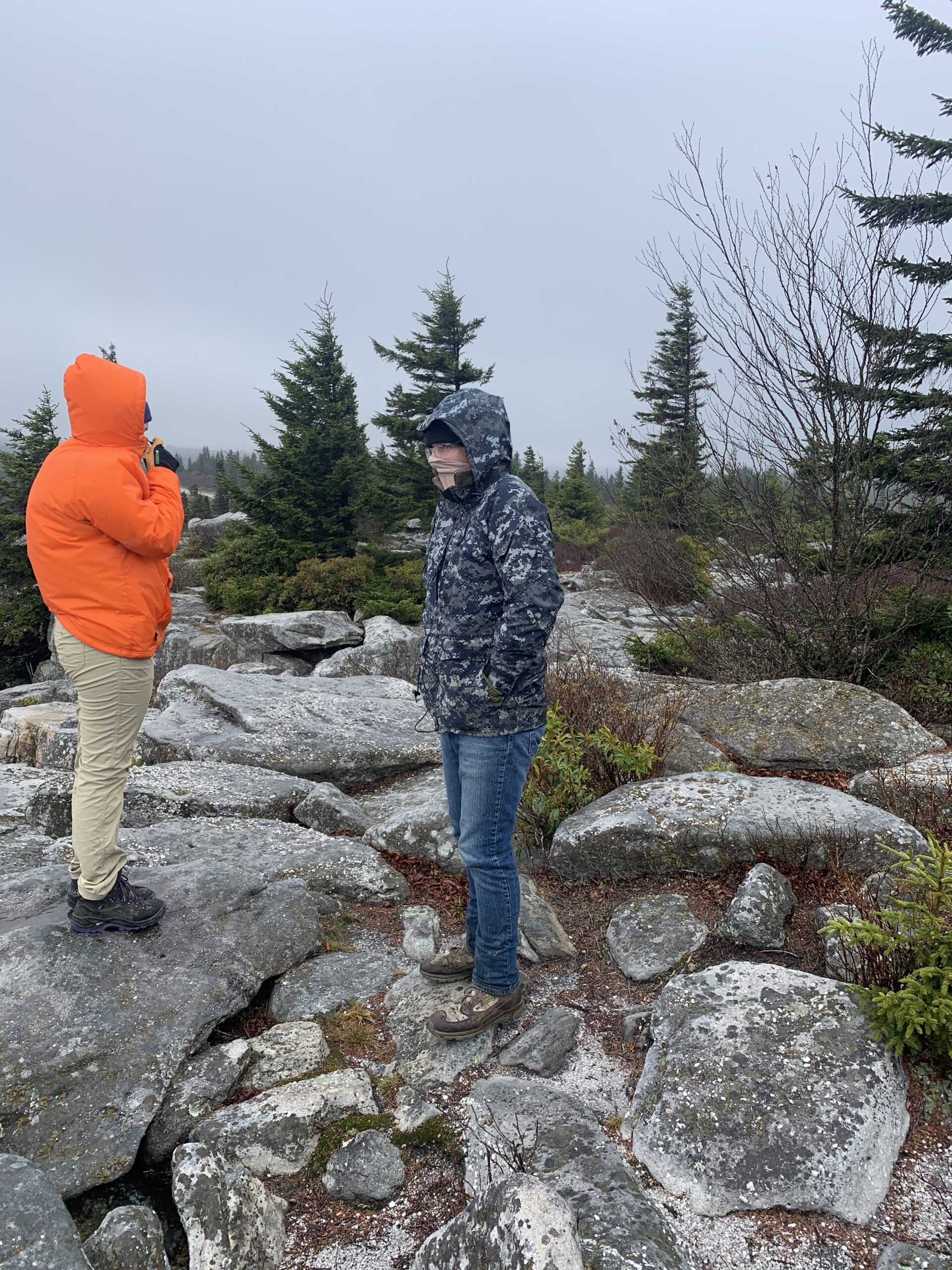

Two of the most impactful gifts from this experience in the Monongahela could not be packed away in my truck. For one, I found a lifelong friend in my co-intern, Ivy. A top-class work partner, a talented biologist, and a supportive sister, Ivy brought immeasurable joy and depth to my time in Marlinton. We both arrived in Marlinton in July as strangers, in the middle of a pandemic, with little direction around how to begin our project. Together, we pushed one another to memorize local species and hone our botanical vocabulary, design and build a seed processing station in the bunkhouse garage, and process over 100,000 seeds. We drove for hours together, commiserating with one another about the state of politics, co-created botany career goals, and encouraged one another in personal growth. We belted the lyrics to classic tune, danced along roadsides while collecting berries, threw piles of rainbow autumn leaves into the air, and braced against winter winds together atop the Dolly Sods ridgeline. Ivy’s presence brought such delight, inspiration, and comfort to this internship experience for me. We plan to continue to support one another for many years to come as we dive into the next step of our botany careers.

The other intangible gift from the Monongahela was a clear vision of a career in field botany. Working at the Marlinton Ranger Station and at Appalachian Headwaters’ native plant nursery provided me glimpses into career possibilities that fit my skillset and interests, but none of those pathways captured my passion as did botany surveys. The first day I went out on a botany survey with the South Zone field botanist, Emily Magleby, I knew I had found my dream job. Before this internship, I had a glimmer of an idea of what a career in conservation and plant work would look like. Now, having shadowed Emily and the other botany technicians (Ken Hiser and Todd Kuntz) on botany surveys and seed collection days, I have had the opportunity to learn about multiple career paths that lead to the same end of working outdoors, with plants. Thanks to mentorship and story-sharing from these botanists, I now have a clear idea on how to refine my skills and knowledge in order to pursue my dream of outdoor, botany-focused conservation work. I can now streamline my career goals and build on precisely the skills I need to work as a field botanist.

With the new year swiftly approaching, I carry with me the gifts of the Monongahela, both tangible and immaterial. This internship experience has left me with a new cat, a solid career network, several mentors, a specialized set of botany skills, and a sense of clarity about where I will be headed. I am unusually enthusiastic about filling out job applications, feeling supported by my new people and finally qualified for the wide array of job possibilities that await me.

A huge thank you to my mentors (Amy, Cindy, Emily, Ken and Todd) and to Ivy for the learning experiences and encouragement during this difficult season. I couldn’t have done it without you.

A Need for Seed

MO’ SEEDS, NO PROBLEMS

Much of October and November was dominated by the drive to go out and collect seeds. Lots of it. We got to explore so much of what the Mon has to offer. We’ve experienced the glorious changing of the colors as we eased into autumn. Never had I seen so much life… which is odd given that I’ve always thought it signified death. Those days will never leave my mind. I felt so incredibly lucky to have been able to go out every day with my co-intern-turn-closest-friend and collect seeds. I’ve also had so many more opportunities to visit Spruce Knob, Dolly Sods and many other unique places to collect.

We were fortunate enough to be surrounded by so many wonderful people who were excited to collect with us. We were able to coordinate a number of collection excursions with insightful and hopeful individuals who wanted to either learn more or simply have a good time outside collecting seeds and having good conversation– or both!

While collecting is a great way to connect with others, we are also actively sowing seeds for the future. We’ve been able to show the old and new AmeriCorps interns the ropes so that they can continue to seed collect and process for the ongoing restoration efforts across the Mon.

At Dolly Sods when the first snow began to fall; my second time seeing snow ever.

We brought along two of the AmeriCorps interns, Julia (left) and Michael (right).

Caroline was barely phased by the freezing cold and strong wind gusts.

On the way out, we spotted a really cool tree.

By the time December came around, I could feel time slow and the reality of my program’s impending end date floating around my brain.

As our time here in West Virginia began to unwind, I also started feeling the pressure to finish processing all of our seeds. I coped with the low-grade stress by creating lists and personal goals for myself to hold on to for the coming month. Along with help from Caroline, I enlisted the aid of the AmeriCorps interns who have helped move along efforts to process all of the seeds collected through the summer and fall.

COMMUNITY LOVE

In the midst of all this processing, I’ve been able to engage myself and get involved in other ways. In early November, Caroline and I were interviewed and featured in the Pocahontas Times, the local newspaper. A couple weeks later, I was tapped to talk about the CLM program and the work we’ve accomplished to a leadership board (composed of all the district rangers across the Monongahela National Forest). Presenting in front of the rangers was nerve-wracking enough but having to present without Caroline compounded my anxiety. Nevertheless, I persevered and received a lot of positive feedback that reassured me. And at the beginning of December, the AmeriCorps (who are also my roommates) and I built a float for this year’s unique drive-in Christmas parade! It was yet another great opportunity to get involved with the community and it was so great to have the support of our district ranger, Cindy Sandeno and a few other forest service members.

-Ivy

A seed in time

It is hard to believe that we are already halfway through December, which means we have one week left in Marlinton before we head home and work remotely until the new year. We have collected more than enough seeds from the available populations from our species list and are spending our final weeks here processing the last few buckets-full of American mountain ash, ironweed, Clematis virginiana, closed-bottle gentian and smooth alder. We may still go out collecting, but only for those seeds which persist into the winter and require minimal processing time: ironweed, staghorn sumac, C. virginiana. By the end of next week, we will have delivered all of our perennial woody plant seeds to Appalachian Headwaters where they will be stored and propagated over the next year. Our annuals will be stored here in Marlinton, since they can be cultivated in situ through wind dispersal and scattering.

We have collected thousands upon thousands of seeds during these past few months. It is quite amazing to see the totals: 14,000 seeds of alternate-leaf dogwood, over 15,000 seeds of closed-bottle gentian, and 15,000 of southern mountain cranberry. Even for species that were scantly populated (catberry, for instance) we’ve collected over a thousand seeds. Our repository will serve as a reservoir of plant life used to pioneer forest succession on strip mines in the Monongahela for years to come. In turn, the plants that grow from our seeds will impact this forest for centuries. Heck, millennia! Theoretically, the seeds we’ve collected will act as the first catalysts in the succession of an enduring red spruce forest. These plants can withstand young soils and grow in direct sunlight, and over the next decade they will morph the rocky restoration site into a haven of biodiversity. Birds and other pollinators will consume and disperse the second generation of seeds across the site, reallocating nutrients to the stripped, rocky soil and forming essential foundations for early-succession tree species. As large trees take hold in the newly rich soil, they will shade out the earliest pioneer species from our seed stock, forming an early-succession broadleaf forest. Eventually, red spruce will grow up in the shaded understory of this forest, transforming its soil composition into a deep humus layer filled with mycorrhizal fungi that push out early pioneer species and favor the dominance of late-succession coniferous tree species, and plants that can survive in the dark understory.

One must zoom out at least one hundred years to see how our daily efforts will endure. Three generations from now, visitors may come across Sharp’s Knob and walk upon a cushion of moss and knee-deep duff teeming with a root network of ectomycorrhizal fungi. Maybe they will breathe the cool, terpene-scented air found only in a copse of red spruce, their eyes comfortably shaded by the dense canopy above. Perhaps they, too, will collect fruits, but instead in the form of Vaccinium berries, mayapples, mushrooms, spruce cones. And on the way out, they’re bound to drop a few on the ground, dispersing the next generation of forest flora.

And the cycle continues…

December’s Update

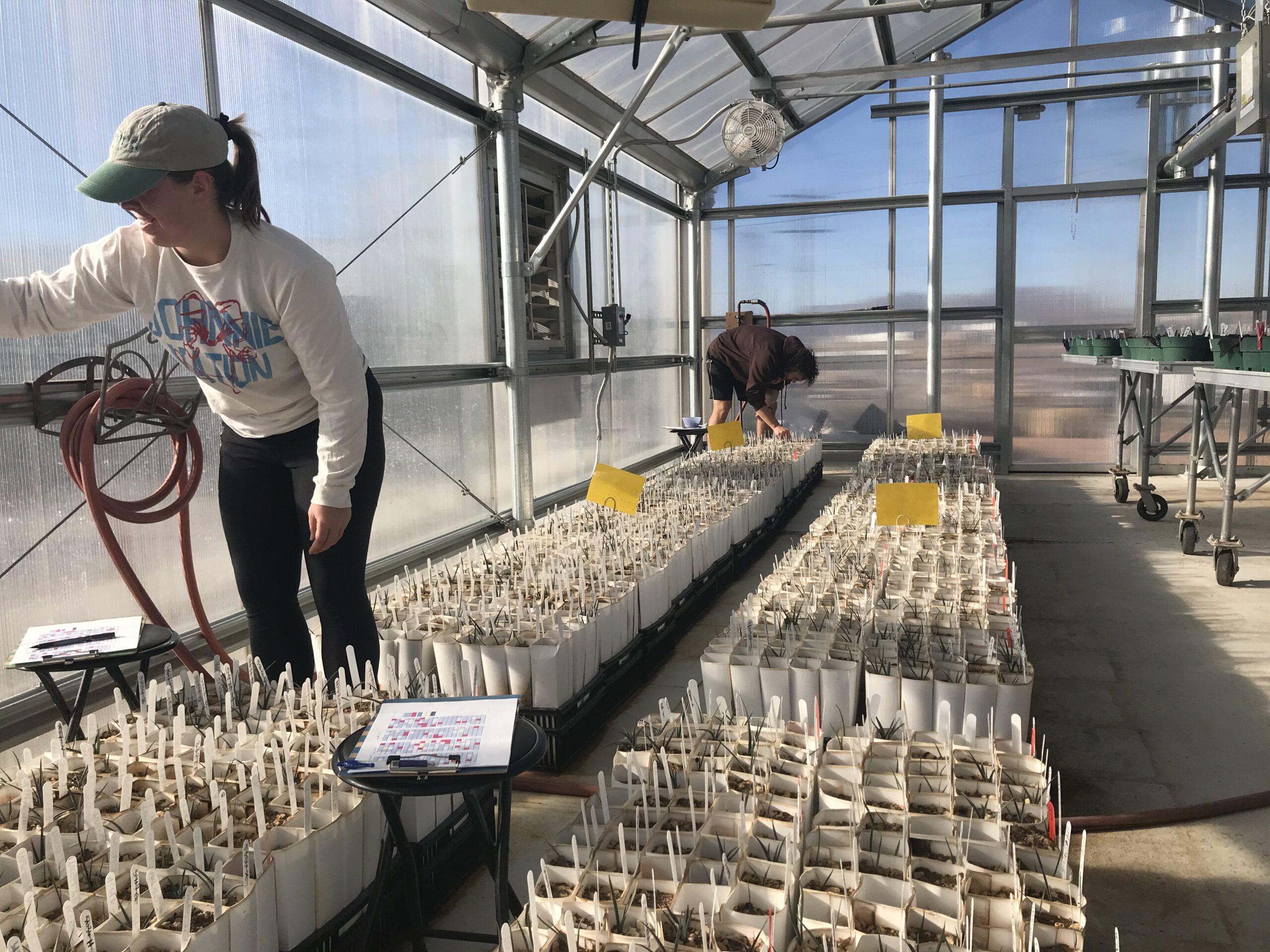

Good news from the JTGP CLM team! We are gearing up our baby Joshua Tree’s for their final transplant into the Common Garden sites across the Mojave. These little ones have come a long way and look very official with their field-ready metal tags.

We still have some maternal lines that are struggling to grow and it will be interesting to see if they pull through or if they simply won’t get to Gardens. As we all know by now: plant research is a dynamic and patient process! All tagged JTs will be transplanted in the gardens over this winter and will have at least a year to grow and develop in their given environments before JTGP leading scientists start to collect genetic and phenological from them (While my group of CLM JTGP interns will be long gone by then, I am excited to check in with our PIs and hear how everything is going in the Gardens).

Because our time here is quickly coming to an end our team has also been super busy organizing, cleaning up and structuring the many data we have been collecting over the past five months. We’ve mastered excel and dabbled in R and are continuing to develop and analyze the loads of info we have on the germination and growth of our JTs.

Saying goodbye to the Owyhees

I can’t believe my time with the BLM is coming to an end! It seems like I only just got to Boise, and now I am embarking on a road trip back home to Austin. I am currently writing this post from Ohlone land, in the ancestral territory of the Muwekma and Ramaytush Ohlone (otherwise known as San Francisco). I have also been wrapping up some data management and writing for the office remotely the past couple of weeks.

Even though it seems like time has flown by this summer, I leave Idaho with so much new knowledge and excitement. While I started this internship with no prior experience in the sagebrush steppe and with minimal exposure to land management, I leave acquainted with the plants of this ecosystem and feeling much more prepared to continue this work in the future. Towards the end of my internship, I even met a former CLM intern who was just hired for a full-time position in my office. It was so sweet to chat about our experiences in the program and spend time in the field together.

Even with COVID posing unique challenges, I still experienced a wide variety of life in a BLM field office: from conducting veg surveys and searching for rare plants to fence construction and riparian assessment to data analysis and writing reports. I was also able to meet permittees and see what it is like to do community outreach in the field office. I even tagged along with our geologist to experience the mineral program. I am so glad for the opportunity to intern with such a welcoming group– my mentor and all of my coworkers were so incredibly kind and knowledgeable and made me feel truly like a part of the team. It was great to work alongside them and learn about all the different parts of the field office.

The past five and a half months have been a period of growth and challenges. In such a turbulent time filled with national and international grief and uncertainty, I am incredibly grateful to have been employed doing work that I love and find meaningful. I will miss the views of the mountains and working with the plants of the high desert. Idaho is a beautiful place, and the Owyhee Field Office had so many sites to explore and plants to meet! I hope that I will be able to come back and visit in the future. Next year’s Botany conference will be in Boise (hopefully, although who knows with COVID), so I might be back in the summer.

I am not yet sure what is in store for me over the next few months, but I fully intend to spend it with loved ones and botanize as much as I can.

Until then,

Lili

Processing seeds, processing thoughts

It finally snowed here in Marlinton, and all of the plant species on our list have officially gone to seed. We spent the past month driving north to collect from the tundra-esque Dolly Sods Wilderness and Spruce Knob, the highest points in the state. As we neared the end of October, our seed collection days shifted quickly from sunburnt, humid adventures to snowy and frigid races to the finish line. Last week at Dolly Sods, we alternated between collecting berries in sleet and jumping into the truck to blast heat on our wet-gloved hands. Collecting seed in cold weather at these higher elevations is an exhilarating experience and reminds me of late July in northern Alaska. The wind smells the same – of encroaching frost and decomposing leaves. There is overlap in foliage as well – caribou moss, stunted, leaning spruce trees and lots of lichen on bare rock. It’s quite amazing how the ecotone at high elevation bogs in West Virginia can bear resemblance to latitudes as far north as the tree line on the edge of the Arctic Circle.

Between collection days, we clean our latest seedstock. It has been an honor to work with Morgan of Appalachian Headwaters, who has been teaching us proper technique for cleaning and storing specific seed types. We have been lucky enough to have access to the cleaning tools and facilities at Appalachian Headwaters, and we are ordering some more equipment for making the same use of our own miniature processing plant here in Marlinton.

I was surprised to find that seed cleaning is mostly intuitive and simply demands everyday resourcefulness. How do you remove cranberry seeds from all that berry pulp? Put electrical tape on the blades of an ordinary blender and chop it up, then filter it out through multiple sieves. How do you remove the outer layer of film from alternate-leafed dogwood? Rub it furiously on a screen and then pick it off with your nails. The whole process of cleaning is unexpectedly familiar, like working soil in a garden. With all that repeated movement, it’s easy to get in the zone and process your thoughts alongside the seeds as you pick seeds apart and wash away the pulp.

Heaps of seeds!

By the end of November, we will have finished up seed collection and will continue to process the seeds we’ve collected. Until next time!

Germination is Possible: an update from the JTGP CLM team

Happy late October from Southern Nevada. The JTGP team is basking in balmy fall weather here and working away in the USGS greenhouse, pampering our Joshua trees. You read right: pampering. Who would have thought these magnificent plants of the Mojave would be so fussy!

You see, it turns out that some of the seeds are quite particular and have decided to fight germination with stark determination. Tucking them into nice damp soil, regulating their day and night temperature in the greenhouse, and diligently watering them makes not a difference.

They simply weren’t having it.

But, little did they know, the same thing could be said for us: we were not having their complete lack of germination.

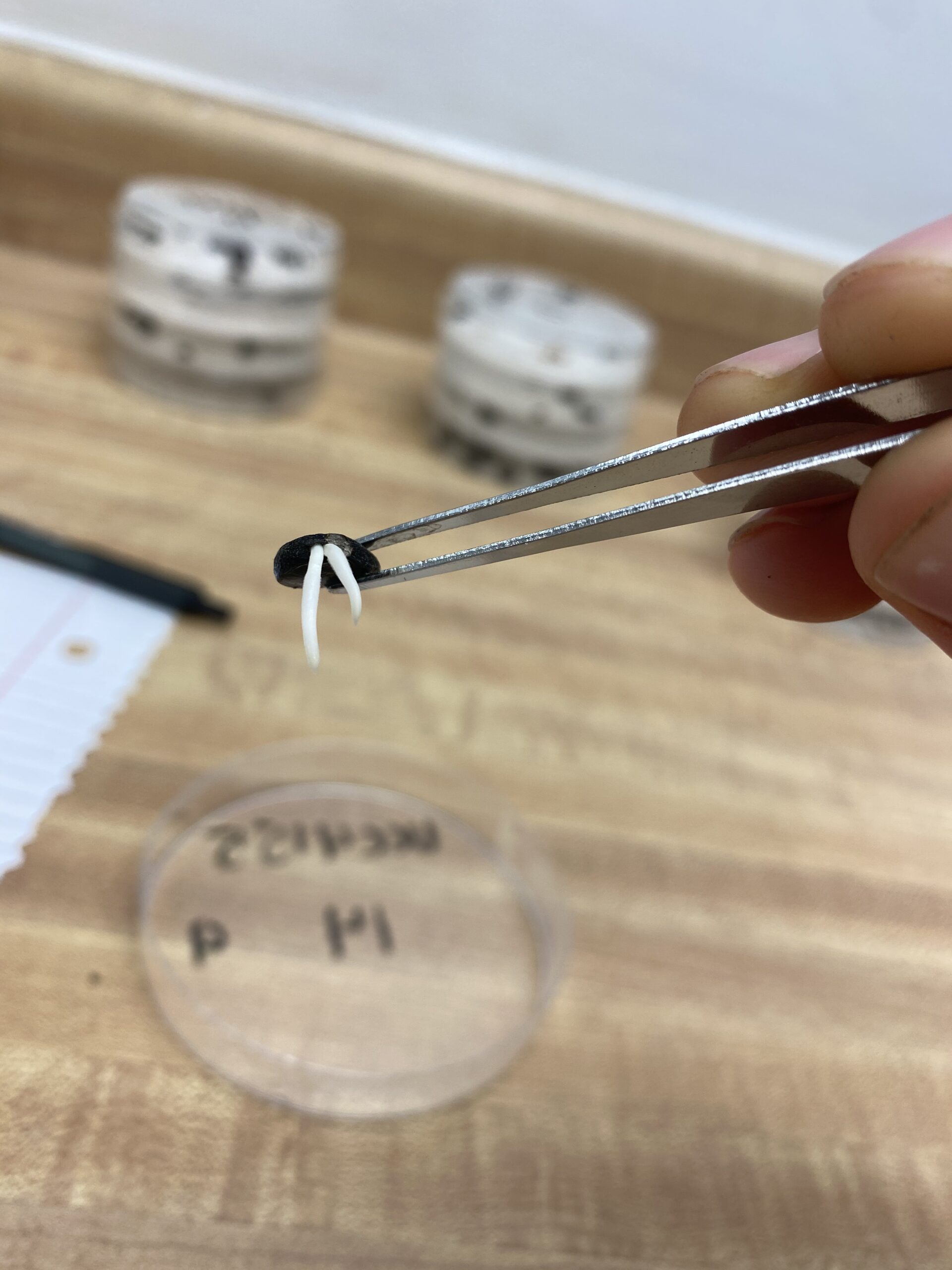

So, we decided to treat these most persnickety seeds like the royalty that they are: laying them out on a damp filter paper in a Petri dish and setting them in a temperature regulated growth chamber to imbibe in warm darkness. We visited them twice daily to alter the chambers day-time and night-time temperatures, gently cleaned them if mold popped up, kept each filter paper nice and damp, and crossed our fingers.

And what do you know-it was just what they preferred! In no time we had lots of happy germinates.

Now, every day more and more germinates appear in the Petri dishes and we scramble to transplant them into their respective plant bands (tall, bottomless cardboard ‘pots’ that allow the Joshua tree’s roots to grow long). And our success hasn’t stopped there. These Joshua trees are (finally) pleased enough to send up bright green hypocotyls and cotyledons. Up next are primary leaves and more, each plant growing as much as possible before its final transplant into the Common Garden sites at the end of the year!

And now we know: despite initial struggles, germination is indeed possible. So grow on Joshua trees, grow on.