WHERE WERE WE?

A few new things have happened since the last time I posted, so let me get you up to speed. After my inaugural blog post, Caroline and I went out on few more botanical surveys. Since we were still familiarizing ourselves with the plant species found throughout the Mon, we were lucky enough to have two incredibly knowledgeable botanists, Emily and Ken, at our office that were open to having us help them conduct rare plant surveys. Although Emily and Ken were nearing the end of survey season and still had a lot of land to cover, they never made our presence feel like a burden. Each of them took time to help us identify species and test our knowledge. It really gave me and Caroline a glimpse into the day-to-day of a career path that we might one day pursue. While it has been nearly a month since the last time we went out on a survey, I often find myself grateful for the fact that we were able to spend so much time with such great teachers. Just like the times we’ve had to endure intense off trail hikes through dense red spruce (Picea rubens) forests and huge patches of stinging nettle (Urtica dioica), my time with Ken and Emily will forever be etched into my memories, my knowledge base, and my heart.

GETTING DOWN TO BUSINESS

After a short delay and a few email exchanges, we were finally on the track to go out to the field to collect seed! With the help of our mentor, Amy Lovell, we were able to connect and meet up with the lead botanist at the Bartow office, Todd Kuntz (about two hours away from the Marlinton office). Before meeting Todd, Caroline and I heard nothing but great things about him from our coworkers; so our expectations we’re pretty high! On our first outing with Todd, he took us to the Dolly Sods Wilderness Area. It was a whirlwind of a day where Todd taught us heaps of knowledge about the plants’ growth habits and seeding patterns.

The following week, we met up with Todd again to collect some new species. Little did I know, we were headed to a trail that led up to the highest point in West Virginia, Spruce Knob. Once we had reached the top, I was completely and utterly awed; not just by the height, but also by the vastness of the view before me. I felt as though I were literally on top of the world. Never in my life had I seen something so ethereal and so perfectly crafted by the Earth. That moment was a beautiful conclusion to a wonderful day of picking seed and picking Todd’s brain about everything related to Allegheny plants.

Although I haven’t yet returned to Spruce Knob, I continue I relish the memories of being on the top of world and yearn to bask again in her glory. May we meet again, Spruce Knob.

WHERE DO WE GO FROM HERE?

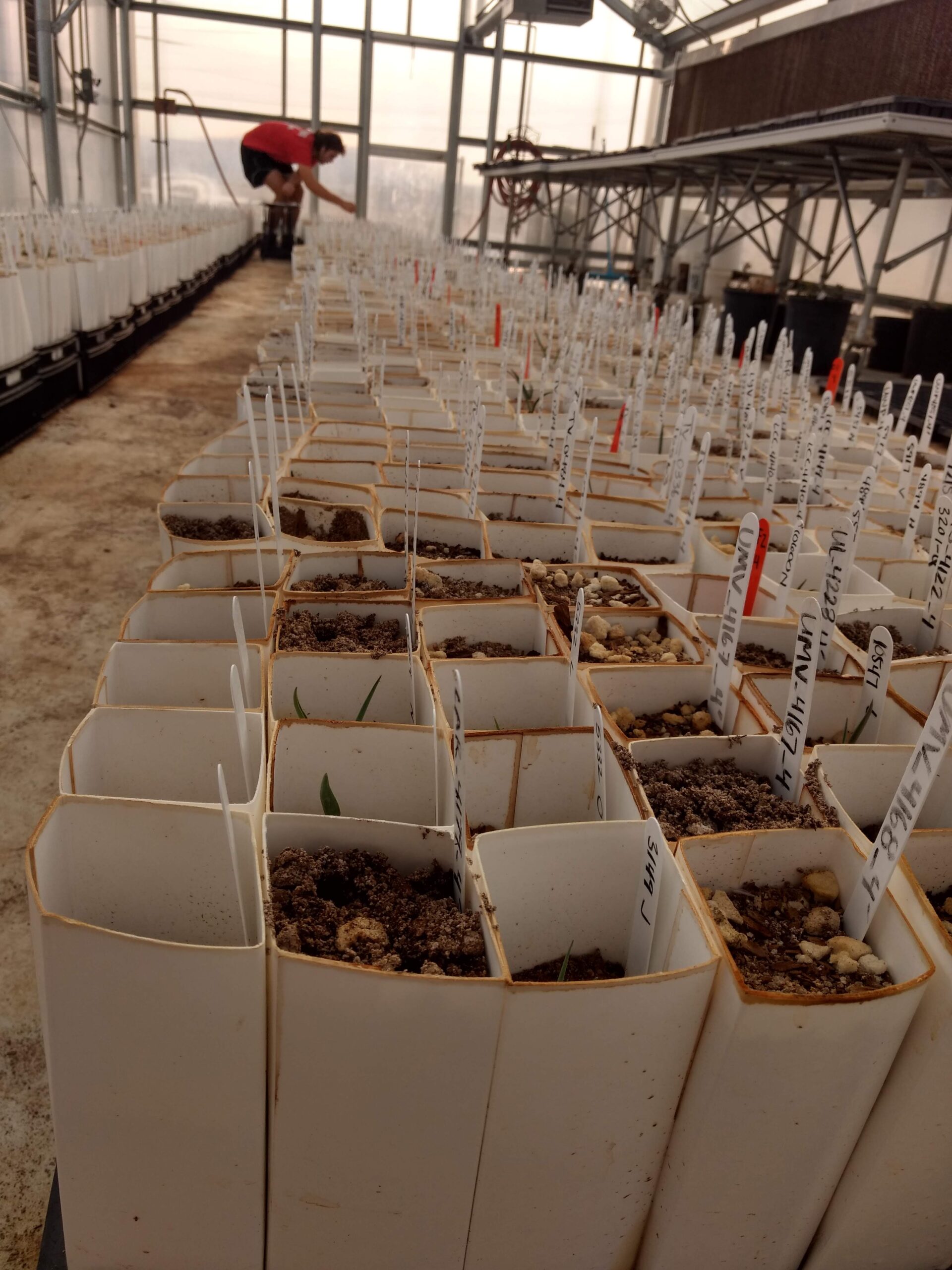

The transition between botanical surveying season to seed collection was gradual, and only slightly overwhelming. With the main seed processing and propagation center becoming more restricted about visitors due to COVID-19, we had to rethink our expectations on how we would learn how to clean, process and store the seeds that we would be collecting over the next few months. We shifted our plans and began researching and learning the seed processing techniques on our own and designed a small scale processing center. At this point, the supplies have arrived and we are ready for setup! I am more than ecstatic about the prospect of starting from the ground up with my co-intern, Caroline. Until then, we’ll be exploring this beautiful state and gathering some seeds along the way.

Gentian spp.

Tawny Cottongrass

(Eriophorum virginicum)

Developing follicles on Common Milkweed (Asclepias syriaca)

Black Elderberry (Sambucus nigra L.) that is not quite ready

-Ivy