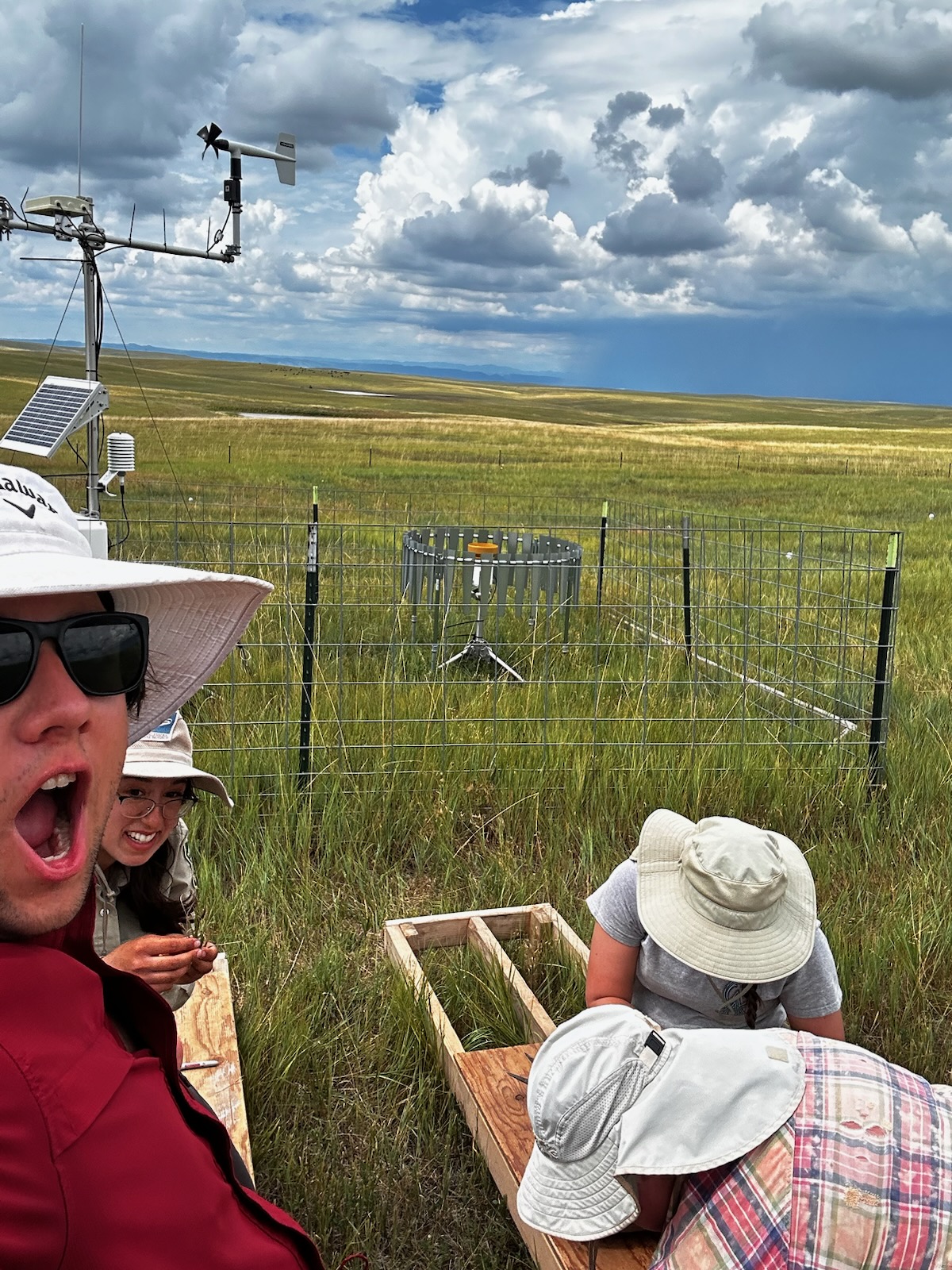

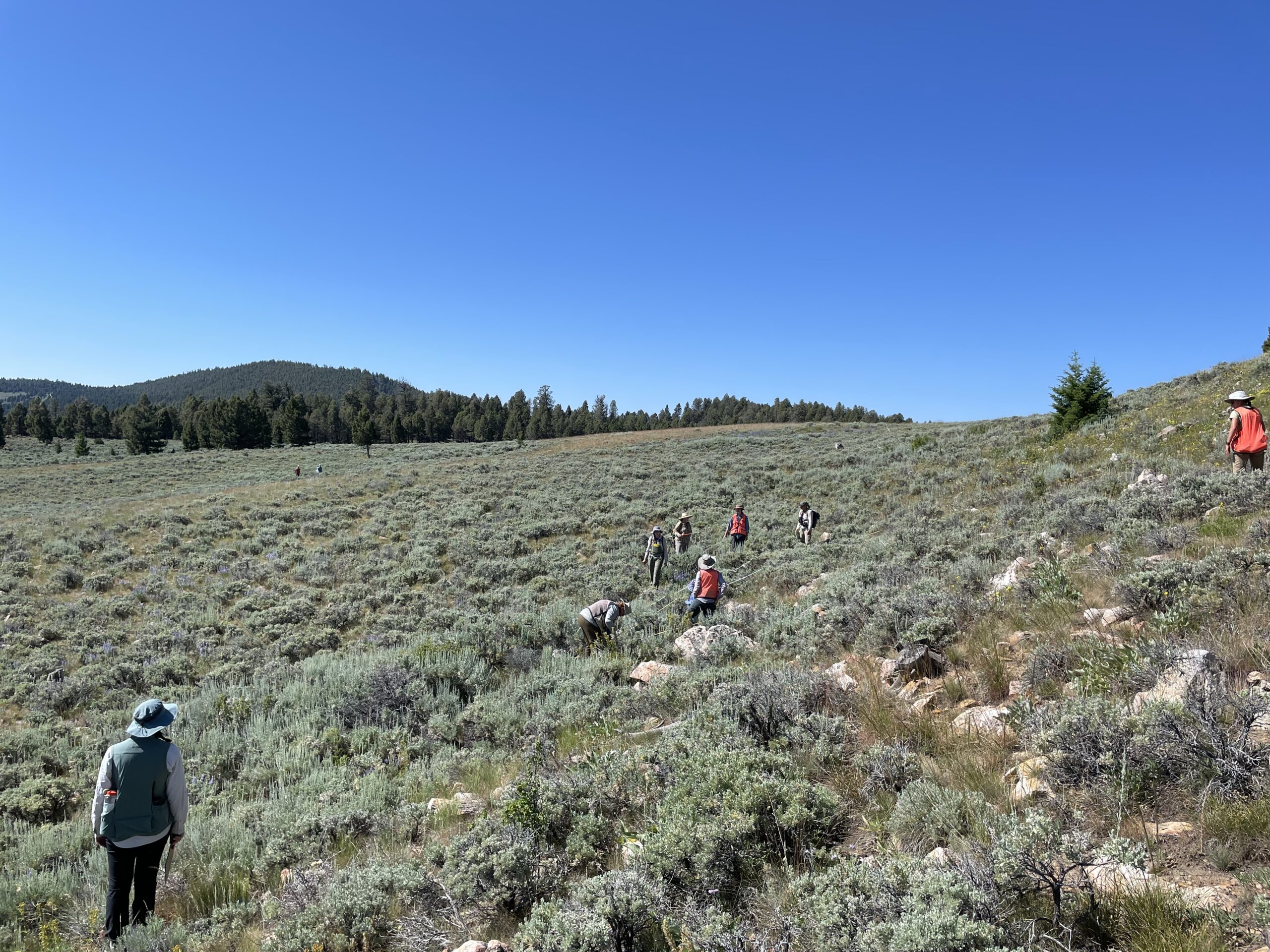

As our team finished the stem demography and aerial cover portion of our summer, we moved onto more solitary activities. Instead of working in groups or pairs on a single plot, we now work mostly alone. Pre-mow clipping was the first to come. We would lay out measuring tapes on each plot and place a small, plastic quadrat with long legs in the correct spot. From there, we roughly sorted the plant material by Bouteloua, warm season, cool season, and cactus. The rest went into a plastic bag to be sorted later in the lab. This continued for all of the other plots. After clipping, the plots were mowed to a specific height.

Then, the fun part came. In order to simulate the trampling from grazing cows, horses from the forest service were brought in to walk over each plot. I gained the official title of professional pooper-scooper. I counted the number of times the horses walked over the plots and removed any fecal matter that could alter the nitrogen levels.

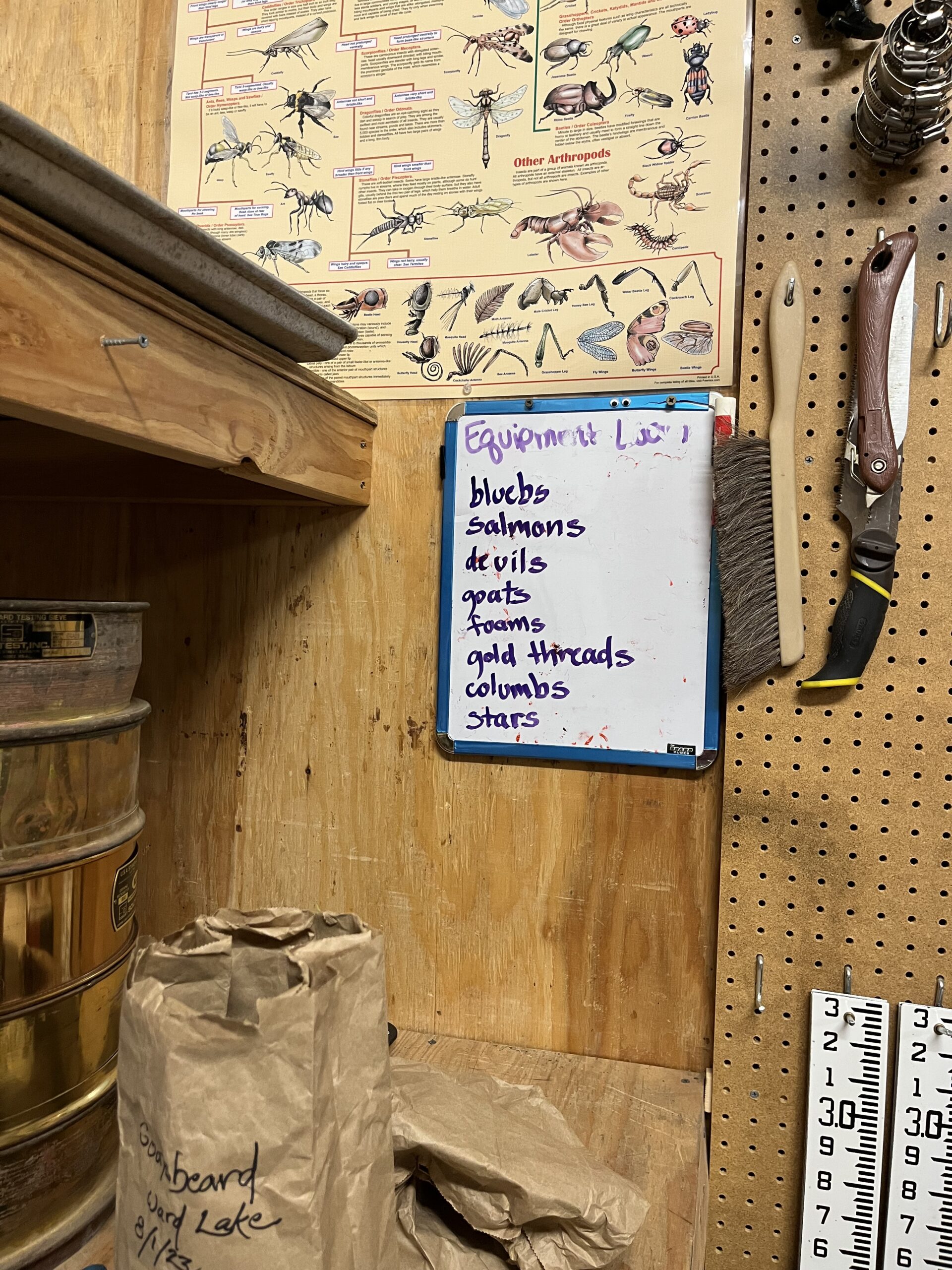

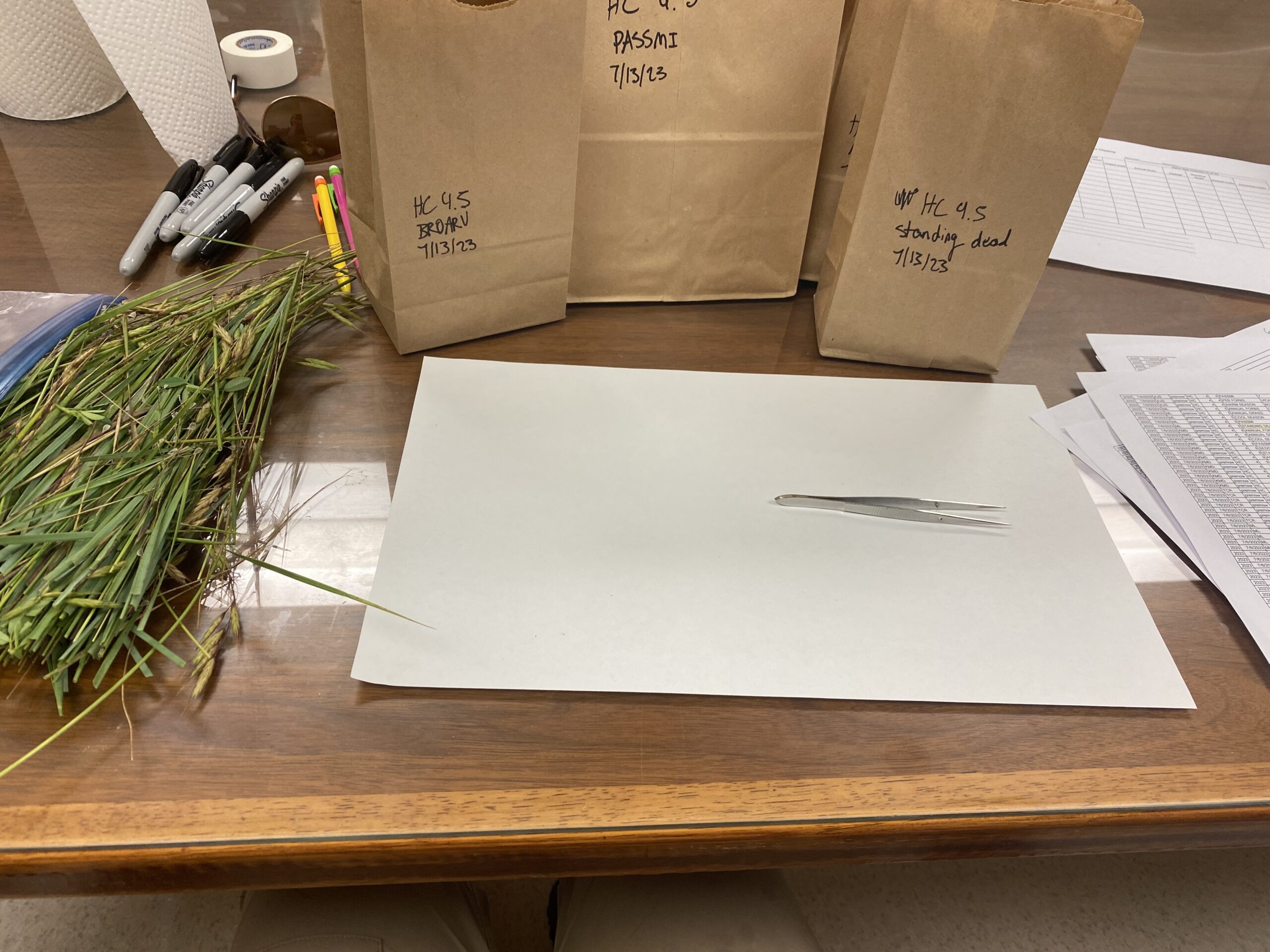

The following week was forecasted to be in the high nineties, so Jackie opted for a week in the office sorting, weighing, and entering data. With my trusty tweezers in hand, I began the long process of sorting through each plastic bag for PASSMI, perennial forbs, annual forbs, and standing dead (along with any misplaced cool or warm season grasses). As we neared the end of the sorting, I weighed and entered data for the remainder of the week. It was a much needed break from the scorching badlands sun.

This past week, we returned to the great outdoors, now conducting post-mow biomass clipping. A few crucial things are different about this procedure. Instead of having legs for the quadrats, we are clipping a few centimeters from the ground. All of the plant material also has to be sorted in the field instead of partially in the A/C. Lastly, the mowing of the plots makes it more difficult to identify the grasses and forbs. As a result, the plots take much longer to clip than before, with my first taking me almost two hours.

Now, to the murder part… The solitary and monotonous nature of last month’s activities has been pretty enjoyable, actually. The clipping and sorting is pretty satisfying and almost meditative. However, the lack of mental stimulation was almost exhausting. My four nearly identical Spotify mixes were wearing thin. So, I decided to start listening to a podcast about historical murder cases and other criminal cases. It was well-produced and kept my attention on long, hot days. However, in an introspective way, I do find it somewhat humorous to be in the middle of nowhere, looking at grass all day, and learning about Lizzie Borden. In a somewhat symbolic way, there was a true murder on the grassland. My team and I were deceived, and the image of our favorite grass was killed right in front of us. BROARV, or Bromus arvensis, is an unassuming, fuzzy little grass. (See Below) Until recently, we thought he was our friend -“Good ol’ Arv”. As it turns out, he’s actually an imposter and he has to go. 🙁

Regardless, this month has been full of learning and new adventures. I can’t wait to see what the next few weeks have in store!