My Summer 2021 sun is beginning to set and I’m taking stock of everything I’ve accomplished during my internship in the southwest. I have really appreciated my time here in the Lincoln National Forest. It’s been great to be a part of a large team-oriented crew. The botany and natural resources teams joined forces this year and with a combined crew of six, we surveyed close to 11,000 acres of National Forest land over a three month period for regionally sensitive, threatened, and endangered plant species.

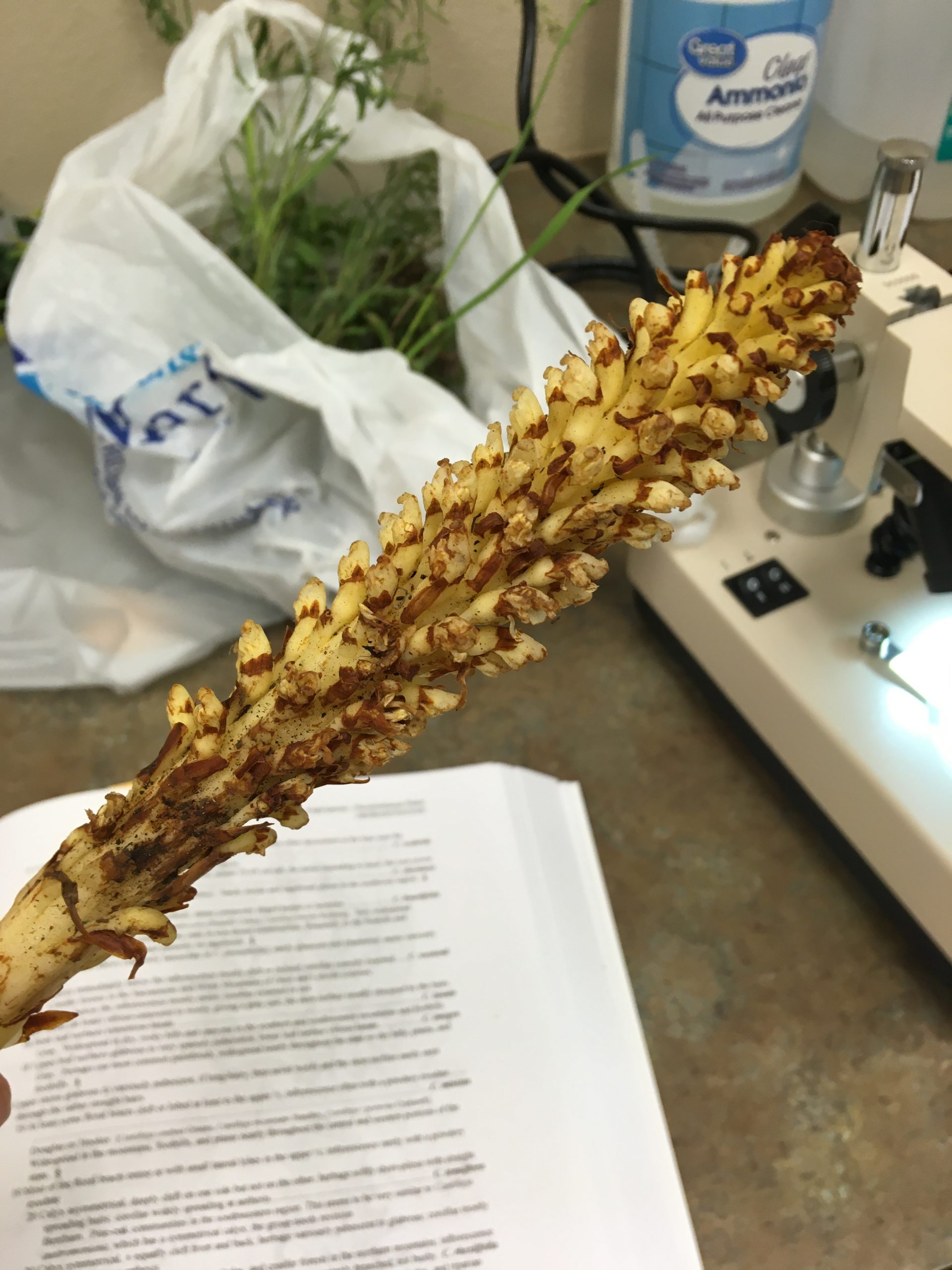

At the end of the season, I honed my skills of reading topographical maps, using Avenza to navigate and surveying the forest through the rain, heat, dense foliage, steep muddy slopes, and countless fallen trees. This was also my first time learning how to key out plants in the field without the help of a thick paperbound dichotomous key and microscope. Instead, I identified many plants with the help of my handy smartphone and a combination of my crewmembers’ knowledge, the Seek by iNaturalist app, the Flora Neomexicana PDF file and the Wildflowers of New Mexico app. Having a smartphone with all the botany related apps has really been a game changer.

Photo credits: Shelby Manford.

One major takeaway for me is that most of the land we surveyed is not ideal habitat for any of the rare plants we were looking for. As a result, we did not find many new populations of rare plants. However, I did get to see what vegetation looks like in a forest that is heavily grazed by cows, wild horses, deer and elk.

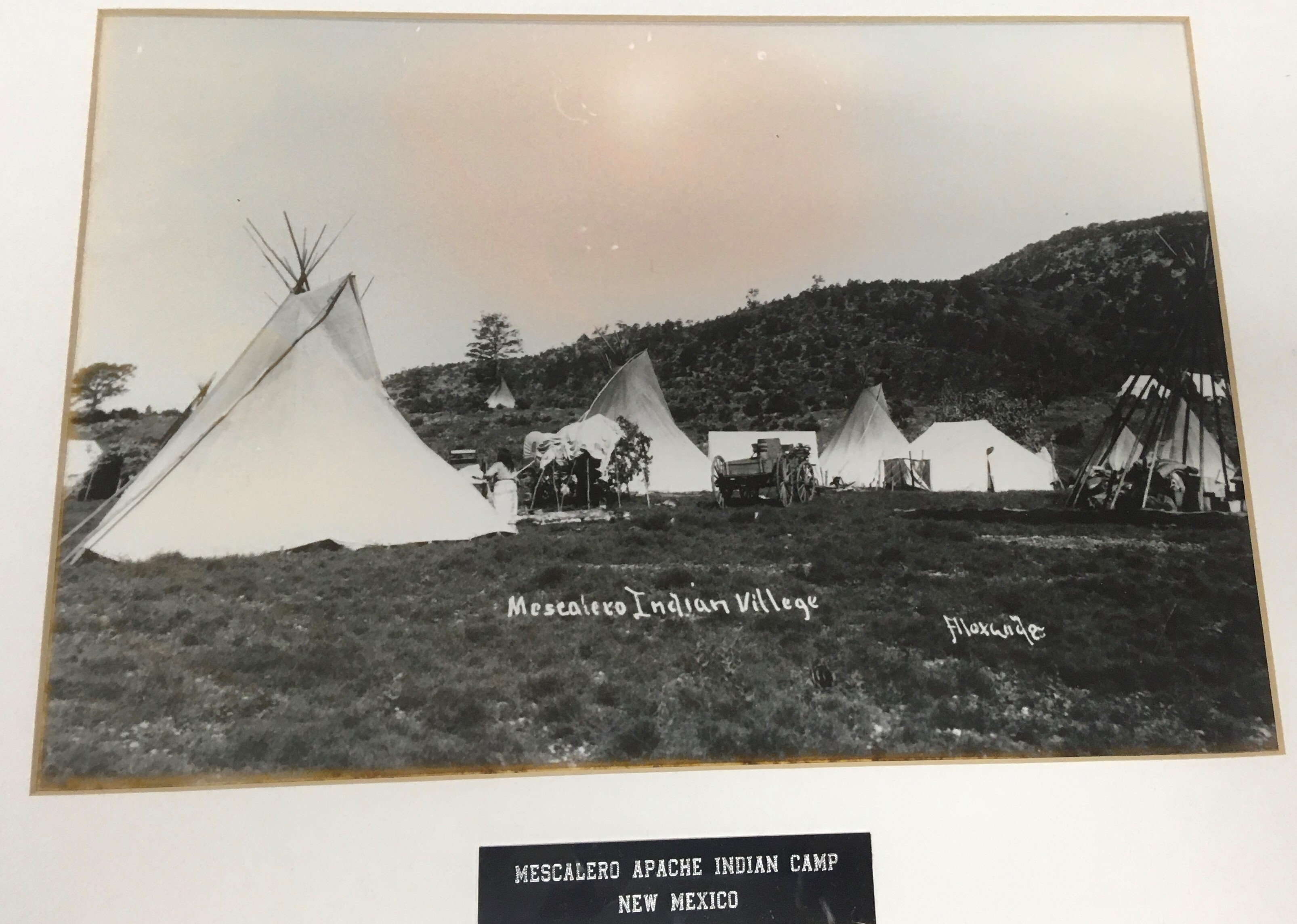

I also got to participate in riparian restoration projects and learn about the importance of watershed management in an environment that has been severely altered since the times of settler colonialism. By working with the Forest Hydrologist, Pete Haraden, and Soil Scientist, Jennifer Hickman, I learned what actions are needed to restore eroded riparian areas.

Photo credit: Shelby Manford.

With the extirpation of beaver by fur trappers last century, a lot of the natural wetlands that were created by beaver dams were lost through erosion, fire, and time. Additionally, a lot of the natural vegetation that traps water has been either heavily grazed or burned in many parts of the forest. This leads to fast running water and deep cuts in drainage areas and canyons that many a time look like chasms. As a result, many of the creeks and streams tend to run fast and dry up quickly after the rainy season, resulting in a low water table and decreased water holding capacity of the surrounding soils. Additionally, the surrounding area’s vegetation frequently converts from riparian species to upland species, which also contributes to the decreased water holding capacity in the adjacent soils.

If a stream or creek is properly restored, it could have water that runs all year long. A healthy riparian area should have slowly meandering creeks and streams that have room to pool up and create ponds and wetland habitat in some areas. The water will also easily flow onto the adjoining wetland under proper functioning conditions. This allows the water to recharge the aquifer and get absorbed by soils in and around the canyons. A restored riparian area could possibly sustain not only the local habitat and wildlife but also local industry and human communities with water throughout the year. Our restoration efforts consisted of building beaver dam analogs, one rock dams, and Zuni bowls.

Another project I’m happy I got to work on was restoration for the endangered Sacramento Mountains checkerspot butterfly (Euphydryas anicia cloudcrofti). I worked with the Regional Botanist, Kathryn Kennedy, for the Southwest Region of the U.S. Forest Service and Melanie Gisler, the Program Director for the southwest office of the Institute for Applied Technology. This butterfly is a candidate for federal listing and there is concern for this species ability to persist, as its population numbers have declined in recent years. In 2020, only 8 butterflies and no caterpillars were observed.

Based on these survey results, a coalition of conservationists from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service; the U.S. Forest Service; the Institute for Applied Ecology; and concerned members of the public; have been collaborating on how to save this species. We got to work on planting the host plant – the New Mexico beardtongue (Penstemon neomexicanus) which is the only host plant for the butterfly in is egg and larvae stages. On a more positive note, this year’s survey for the Sacramento Mountains checkerspot butterfly have revealed the presence of 22 butterflies and 80 caterpillars on the Sacramento Ranger District of the Lincoln National Forest.

I would like to thank my mentors Aurora Roemmich and Megan Friggens for providing such a great internship opportunity. Thank you to Pete Haraden and Jennifer Hickman for teaching us a little bit about hydrology and soils. Much appreciation to my crew members for providing camaraderie and support throughout the season!