October is over, and so is the end of our field season. Li, our Montana Conservation Corps Fellow, left us at the beginning of the month (and on Employee Appreciation Day too?!), and it was sad to say goodbye. She really made the bunkhouse feel like a bunkhome. But the show must go on – we had botanizing to do. Since we’ve finished monitoring and our target species have dispersed their seed, most of our time has been spent establishing pollinator islands.

The area we planted in, Schultz Saddle, burned in the 2022 Trail Ridge wildfire, which made it a good candidate for an area we could put in native plugs as a food source for bees. We spent several days swinging hoedads and recording the locations of our plantings so the crew can monitor the site next year. Schultz Saddle is pretty high in elevation, and it snowed up there for most of the past two weeks (which made me very happy).

This month, Cicely and I got to do more cross-training. First, we went out with Hydrology to monitor the chemical composition of the Bitterroot River, specifically looking for the stream flow and concentrations of nitrogen and phosphorous. Later, we helped Soils complete some surveys, aka hiking all day taking samples. I looooove getting my hands in the dirt, so it was pretty awesome. Amanda taught me about how forests store carbon and how soil heals from disturbances over time. It was really interesting because vegetation actually plays a big role in soil healing by breaking up compaction through their roots and cycling in different nutrients!

In my free time, I’ve been trying to fit as much life into my last month here as possible: going to Hamilton’s Apple Day, visiting a friend, participating in the town’s Witch’s Ride, and playing night frisbee with light up vests. I don’t want to take a second for granted; this really is a wonderful place with wonderful people.

Also, Cicely and I hiked Trapper Peak.

It felt like a perfect wrap-up to our season because we have stared at this mountain from a distance for five whole months now. We could see it from basically everywhere we surveyed in the forest, standing watchful over us. At 10,157 feet, it is the tallest peak in the Bitterroots.

The ascent was absolutely gorgeous, and I was elated to see a mature whitebark pine stand on the way! Hiking was steep, tiring, and so much fun. Cicely and I agree that rock scrambling is one of our favorite activities. I felt a huge sense of achievement reaching the top and seeing Darby from a new perspective, looking down at the valley thinking, “Wow, it all seems so different from up here…”

… which is kind of how I feel at the end of this internship. From the smallest details (identifying a species as part of Asteraceae by its bracts) to the big picture (the impact of climate change on plant migration and seed sourcing), I’ve learned so much from this experience. Plus, surveying, monitoring, and seed collecting – all of it is part of a larger effort to keep plant biodiversity in US forests. So I’m proud of the work we’ve done.

Things I’ll miss:

- Scouting in our rigs Rusty (RIP) and Betty White

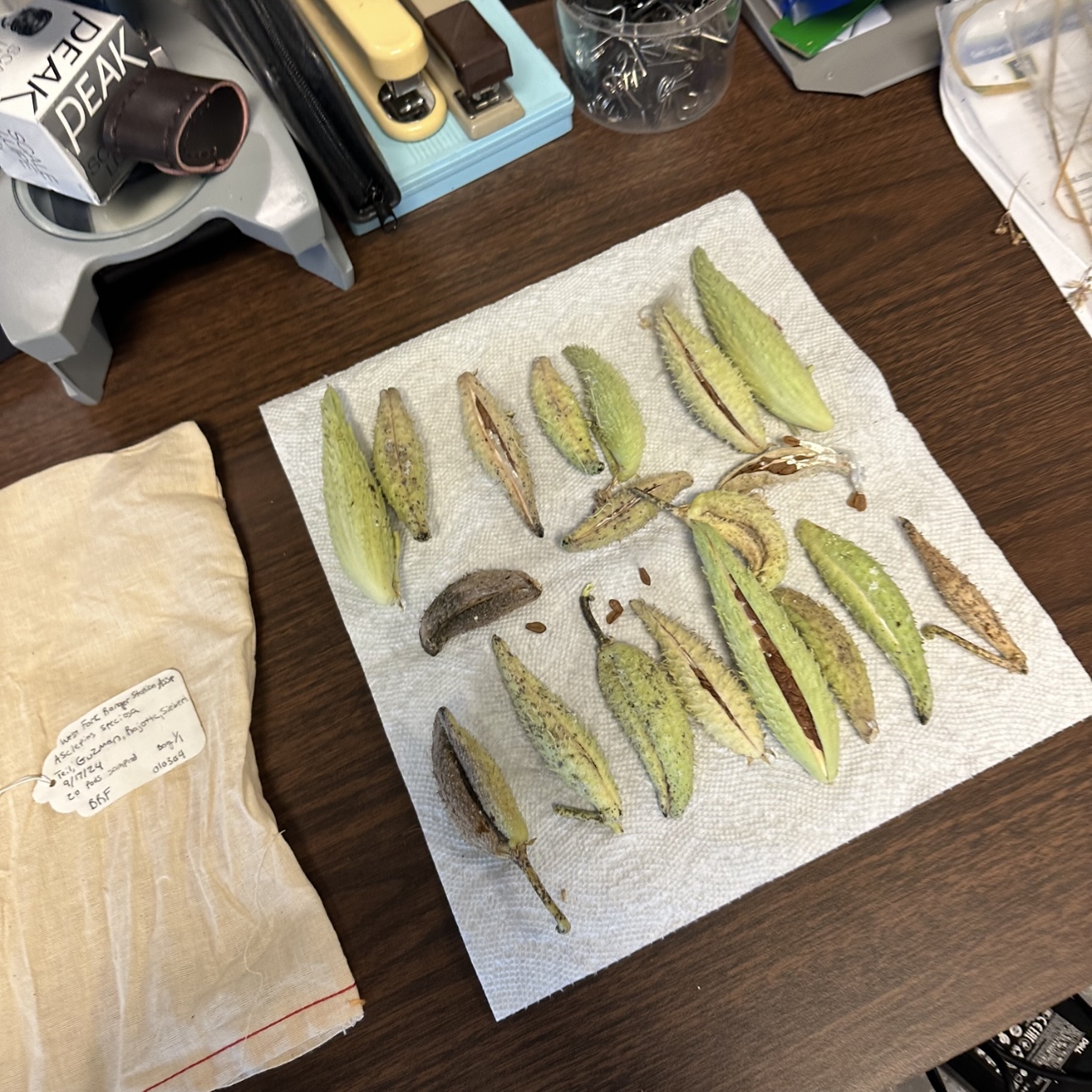

- The peacefulness of picking seeds with pappus

- Li always pointing out the moon

- Pestering Laura with wetland fun facts

- The mountains

- Pasta dinners in the bunkhouse

- The crew replacing ‘Cecelia’ with ‘Phacelia‘ when we sing the Simon & Garfunkel song

I’ll be sad to leave, but as I prepare to trade in my Lesica for Flora of Virginia, all I’m feeling is grateful. Laura, Lea, Hannah, and Li made the Botshots such a great crew. Cicely was the best co-intern anyone could ask for. I’m taking these memories and lessons with me. Thank you, Bitterroots, it’s been real.

Signing off,

E